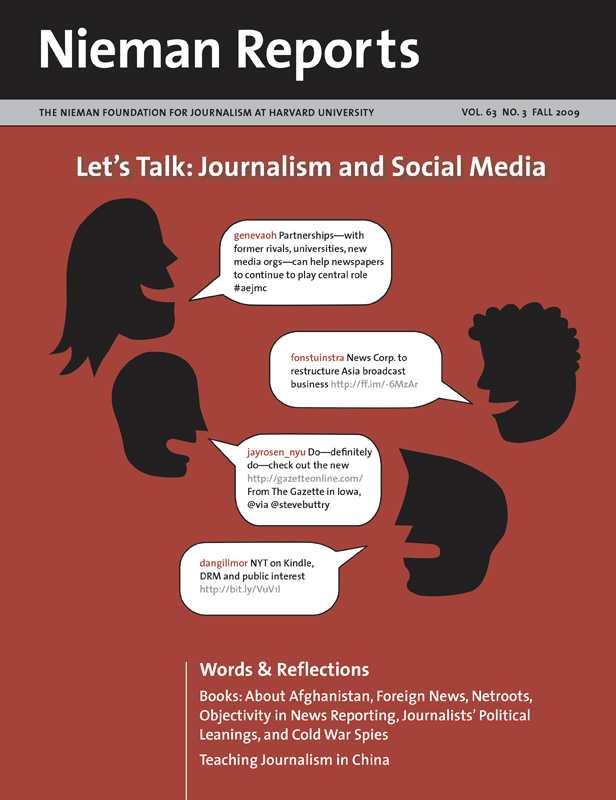

Let's Talk: Journalism and Social Media

From blogs to vlogs, Facebook to MySpace, Twitter to Flickr, Delicious to reddit, words and images bounce around the globe, spreading wide and fast. Journalists are adapting to the ever-shifting terrain carved out of these conversations. In this issue they describe changes in how they work and what they produce, explore emerging ethical issues, and propose principles of active engagement. In Words & Reflections, essays touch on foreign news reporting, Afghanistan, netroots, objectivity, journalists’ political leanings, and Cold War spies.

This could be the finest era to be a journalist. My daughter, Emily Witt, a recent graduate of the Columbia University Graduate School of Journalism, got a summer gig at ProPublica. Her first coauthored story highlighted proposed cuts to California’s state crime lab and was picked up by The Huffington Post. Within 24 hours there were 177 comments. Think back just 10 years: To write a story and receive 177 letters would have been a miracle. Frankly, it never happened in my 30-year career.

Veteran reporter Howard Witt, this time no relation, experienced his own social media miracle. Working out of the Chicago Tribune’s Houston bureau, he wrote a story about Shaquanda Cotton, a 14-year-old black girl who pushed a hall monitor at her school and was sentenced to seven years in prison. Pretty harsh punishment for a push. The real twist in this story, however, was that this same sentencing judge put a 14-year-old white girl on probation after she burned down her family’s house.

He filed the story, knowing it was a good one, but, as he told me in a video interview, he didn’t expect much reaction. What happened next surprised him. “Within a matter of a couple of days I started to get hundreds of e-mails from people who had encountered that story through e-mails, through blogs, through places far removed from the Chicago Tribune’s Web site. … I started to realize there was this network of blogs out there devoted to African-American issues that were actually distributing that story.”

Turns out that the African-American blogosphere picked up Witt’s story, and it had gone viral. So much fervor erupted over the apparent injustice that in three weeks Cotton was released from prison.

For my daughter’s generation, social media is part of their daily milieu. For Witt, witnessing the power of the African-American blogosphere was an epiphany. So when he traveled to Jena, Louisiana, to report on six black teenagers charged with attempted murder following a fight at a high school, he didn’t wait for the bloggers to find him; he e-mailed them to suggest they read his stories from Jena. In time, word spread through this blogging community and the young men became known as the “Jena Six.” Soon, more than 20,000 people descended upon the tiny town of Jena to protest, some riding more than 20 hours on buses. As far as Witt could tell, the protest organized itself with no central leader.

Of course, these events would not come as a surprise to New York University professor Clay Shirky, who wrote the book, “Here Comes Everybody: The Power of Organizing Without Organizations,” which was published last year. Nor would it surprise Howard Rheingold whose book, “Smart Mobs: The Next Social Revolution,” published in 2003, says in a nutshell, “Smart mobs consist of people who are able to act in concert even if they don’t know each other.”

Investing in Social Justice Reporting

This notion of crowd action being propelled by online exchanges raises a related question: If people organize themselves for social justice, will they do the same to support—which in this case means invest in—journalism that gives people reliable information about civil rights and social justice? After all, if Witt (or another reporter) is not there to report these stories, it’s unlikely that the injustice Shaquanda Cotton faced or the trial of the Jena Six would have generated this kind of public response. Yet, in working for the Chicago Tribune, his job is hardly secure. [Witt has since left the Tribune and is now senior managing editor for Stars and Stripes.]

If reporting jobs aren’t there for my daughter and her peers, will such stories be told? In some ways, it is ironic that only when the crowd recognizes the invaluable role that high-quality journalism plays in social action—and realizes that such reporting isn’t done for free—will social media and journalism become truly linked in common purpose.

Would this crowd be willing to invest in journalism—to “own” newsrooms like fans own the Green Bay Packers? Coverage of civil rights and social justice issues could be made the core of a digital news organization, national or global in scope. Or the creation of such content could be done in partnership with other journalistic enterprises. In an interview I did with John Yemma, editor of The Christian Science Monitor, he said that his online newsroom of about 80 people costs about $7 million a year. With that as a gauge, a 20-person “newsroom” could exist for about $2 million a year.

What percentage of the 20,000 people who came to Jena might want to become owners of such a journalistic cooperative with a stable of editors, investigative reporters, and feature writers whose job it would be to cover these beats?

The civil rights and social justice story well runs deep and its issues are complex. What follows are some starter ideas, stories that even now don’t receive the attention they should:

- The prison industrial complex where thousands of people languish for selling a few joints or for having a drug habit

- The immigrants, who will, in time, save the United States from aging itself out of existence

- The buyout story in which older workers are cast out because they cost too much.

Or stories similar to those Barbara Ehrenreich highlights in her book “Nickel and Dimed” and reinforced in her New York Times op-ed, “Too Poor to Make the News.” There, she paraphrased a social justice worker in Los Angeles:

The already poor … the undocumented immigrants, the sweatshop workers, the janitors, maids and security guards had all but ‘disappeared’ from both the news media and public policy discussions.

Will those marginalized by race, ethnicity, gender or sexual orientation, age discrimination, or economic circumstance decide it is in their interest to become part of a community-supported journalism cooperative devoted to covering social justice issues? Of course, the promise on the other side of the equation would be adherence to the standards and ethical practices of journalism and a rejection of pressures to act as a public relations’ vehicle.

Ruth Ann Harnisch, president of the Harnisch Foundation, believes enough in community-supported journalism that she provided a $1.5 million pledge to enable me to start the Center for Sustainable Journalism at Kennesaw State University, outside of Atlanta. This center has the capacity to develop such a project. From the Jena protest, we know the crowd exists. And we know that in the African-American blogosphere—and other blogging communities—resides the power for self-organizing. If these various online communities can find ways to come together in common purpose—and a social justice journalism infrastructure is in place to greet them with the “ask” to potential investors—then a grand experiment in democracy will be launched, and it will be grounded in an emerging model of sustainable journalism.

Interested in joining? We are ready to begin.

Leonard Witt holds the Robert D. Fowler Distinguished Chair in Communication at Kennesaw State University and is the founder of the Center for Sustainable Journalism.