In September 2001, after the establishment of Alejandro Toledo’s government, protesters in southern Peru demanded that the government follow through on its promise to build a highway to link Peru to Brazil. Photo courtesy of Archivo Diario La República.

A Brazilian woman journalist tells us that her worst boss had been a woman. Another, a Chilean colleague, remarks that competition in newsrooms was very stiff, and that being a wife and mother is forbidden for women aspiring to leadership positions. The editor of one of the largest dailies in Argentina says that even today editors—most of whom are men older than 50—address women reporters not by their names but by a caramelized, “Hey, sweetheart.”

During three different workshops—sponsored by the International Women’s Media Foundation (IWMF) in Latin America and held in Managua, Nicaragua, Buenos Aires, Argentina and Quito, Ecuador during the first half of 2001—stories like these were told again and again. More than 70 women reporters from 16 Latin American countries attended these workshops, and the issues they raised and the stories they told seemed to follow predictable patterns as they reflected on work environments, the possibilities of leadership in Latin American media outlets, and hopes for the creation of organizations that foster training and networking and that provide professional and personal support.

I was the facilitator during the leadership workshops at each of these gatherings, so I can identify some shared characteristics despite the particular circumstances of the individual countries from which participants hailed. There are logical differences based on the level of development of the media outlets, which is closely tied to the economic development of the respective country.

As I listened, it became apparent that women journalists’ leadership in the work environment is a collective aspiration that is still far off in the distance despite the huge contribution of women and the infamous feminization of the journalistic field. The situation can be imagined as a triangle whose apex is filled mostly with older men who have difficulty welcoming the few women who manage to break the barriers to the top. Women journalists mentioned the tricks used by male colleagues to make them feel out of place, as though they are invaders. Some men use off-color jokes; others relate to women based on a father-daughter dynamic; others attempt sexual advances, which reinforce the exclusion of women from a sphere reserved for men.

Those women who do assume leadership positions must sacrifice their personal and family lives to reach their professional goals, and in some cases they must relinquish their aspirations for starting a family if they want to continue ascending the ranks. Sexist commentaries about pregnancies and the special benefits often requested by working mothers are commonplace in Latin American media. Another argument used when determining promotions is whether women are ready to take on risky and demanding assignments that require more responsibility. Even today it is normal for women editors to work on supplements geared towards women or families, or departments related to health or children. It’s unlikely that a woman would be at the helm of departments dedicated to science and technology, the economy or computers.

And women who have managed to reach decision-making roles in the media don’t feel the obligation to be trailblazers for other women. To the contrary, the pioneering generation does not recognize mentoring as a duty, and poor relationships between women supervisors and women subordinates are quite common.

The Brazilian journalist who shared the story of her awful relationship with her female boss explained that she could not communicate effectively with her boss. Sometimes the reason was as absurd as her being more elegantly dressed than her superior was. Some comments that surfaced during the workshop dealt with the fact that some women, when commenting on other women’s work, are incapable of separating personal attributes from professional qualifications. Some pointed out that it’s common for a man, when speaking about another man, to comment, “he’s a terrible person, but an excellent worker.” It’s almost impossible for a woman to state the same.

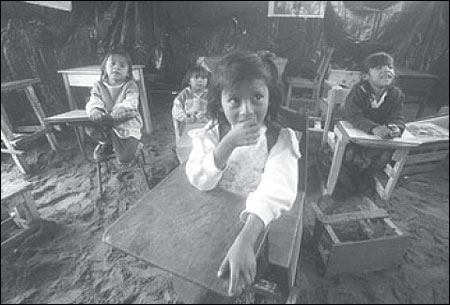

In a rural community outside the capital, children learn under precarious conditions, in plastic classrooms with dirt floors. Photo courtesy of Archivo Diario La República.

What happens next?

Participants in the leadership workshops stressed that it is essential to work in several areas to try to bring about constructive changes.

The professional: There’s a need for continuous training that would enable them to compete for professional opportunities on an equal footing. They considered business training fundamental in breaking the stereotype that women lack business sense and leadership.

The personal: Women’s self-esteem must be bolstered with tangible action, such as having them contribute to determining what is considered news. Some characteristics that are considered feminine are essential for improving the quality of the news media and for satisfying the public’s new demands. It’s also necessary to mention women’s ability to organize, participate and lead professional entities, which allows for more democratically led organizations, thereby changing the traditional personality-based and tyrannical leadership methods that have characterized the media throughout history.

The collective: It’s important to reinforce the networks and groups established by women journalists, allowing them to connect with colleagues who share common interests.

There was, however, an awareness that any of these efforts to promote women’s leadership will not yield the desired effects if some problems, which the workshop participants considered substantial, are not addressed first. Two of these appear to stand out in the minds of these women journalists: the conflictive relationship between women colleagues and the lack of conflict resolution training.

To improve the woman-to-woman relationship at the workplace, gender solidarity needs to be promoted without defaulting to permissiveness based on gender. Solidarity should be regarded as a tool for collective success, as a way to generate equal or better-abled female leadership that will lead the way for other women. After all, an intrinsic characteristic of leadership is the training of new and better leaders. Passing experience down and guiding the next generation towards personal and professional success demonstrates the leader’s worth.

The IWMF workshop participants also discussed conflict resolution training and the fear of addressing conflicts. It is an area that is lacking and that must be addressed in this difficult process of strengthening women journalists’ leadership in Latin America. Female stereotypes depict women as being afraid of confrontation and of asserting their personal points of view. The reality is that as women we have grown up avoiding conflict; that behavior has defined our filial and social environments, especially in Latin America. But it is impossible for women in the media to survive, and even harder for them to become leaders, if they lack the skills necessary to deal with conflict.

Women managers and editors gave concrete examples of how they gained such skills through formal training but also through assuming leadership positions in mixed gender situations where colleagues challenged their orders and decisions. Journalistic ability does not lead to leadership ability. It is necessary to be a good listener and to give orders when necessary. For that, women will no doubt need training.

Lastly, I’d like to share my enormous pride in the incomparable experience of those days of collective reflection and learning with Latin American colleagues. Our long hours of work, our debates, our laughter, and our shared dreams were characterized by solidarity, understanding and a sisterly bond with which we faced the obstacles we have in common.

There were women who, based on personal merit, held directorial positions in their companies, and they shared their experience with young professionals who dream of a successful career. Also, journalists who work in the alternative press shared their point of view with those who were hesitant about embracing the feminist cause. The extraordinary Colombian journalists, who confront political violence daily, the Peruvian journalists, who confronted a dictatorship and immorality with the resolve of their denouncements, and those from Argentina, Brazil, Chile, El Salvador, Paraguay, Uruguay, Ecuador, Venezuela, Panama, Honduras, Guatemala, Nicaragua, Mexico and Costa Rica, each of them shared a part of her personal and professional history, as well as her doubts and convictions and her hope and faith in a better future.

I urge women journalists to continue working towards a true leadership in this part of the hemisphere.

Blanca Rosales, a media consultant, is currently a media education advisor to the government of Peru. This article was translated from the original Spanish by Juleyka Lantigua.