The conundrum news executives around the country have been facing for years is a basic one: What do you throw overboard, and what do you keep?

For Martin Kaiser, editor of the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel since 1997, the answer has been clear: Watchdog journalism is the key to the franchise. So even as the newsroom shrinks, the commitment to being a watchdog grows.

Kaiser could have gone another way. He could have pushed out his most experienced and expensive reporters and prioritized daily stories from Milwaukee’s moneyed suburbs. But the suburban bureaus were one of the many things he threw overboard instead.

“As the newsroom started to get smaller, I really thought we needed to get a lot more focused on what we did and what we didn’t do,” Kaiser says. He concluded: “Let’s do what matters. And the other stuff we aren’t going to do anymore.”

It helped that the Journal Sentinel’s parent company owns a chain of weeklies that are distributed with the newspaper so the small-bore suburban coverage didn’t entirely disappear. But it wasn’t just the bureaus that got cut. “Almost every department is smaller than what it was before,” he says. “You can’t but help having to give up stuff if you go down 70 or 80 people.”

“Do we miss stories? Sure,” he says. “There are profiles and features stories that I’d like to do that we probably don’t get to.” And, he notes: “I’ll admit that even with the suburban weeklies, we’re not covering as much as we used to do.”

But most of the stories they don’t do are “the sort of daily story that doesn’t mean much.”

By contrast, watchdog journalism is way more fun—and, Kaiser thinks, better for connecting with readers. So in 2006, Kaiser started building the Journal Sentinel Watchdog Team, “whose mission,” according to its website “is to work to expose wrongdoing, dysfunction, inequity and injustice and strive to hold accountable those responsible through meticulous case-building and compelling story telling.”

The much-celebrated team now has a dozen members. Their orders: “You’ve got to do stories that matter and you’ve got to have impact.”

“I want people to know that the Journal Sentinel is having an impact, and stirring things up—that you’ve got to see what they have on Sunday in the newspaper. You’ve got to read what they’ve got online,” Kaiser says.

It’s not your typical investigative team in several ways. Its members don’t all sit together in a corner somewhere; they’re physically spread out among the beat reporters. Their stories tend to emerge from reporting, rather than from ideas that come from the top.

And although activism can be a dirty word in journalism these days, Kaiser isn’t afraid to push for change—supported by the facts, and based on widely shared values.

“What I love about it is that in a way it’s the old-fashioned newspaper crusade,” he says. “I think you should stand up for what you believe in and say that’s what you’re doing.”

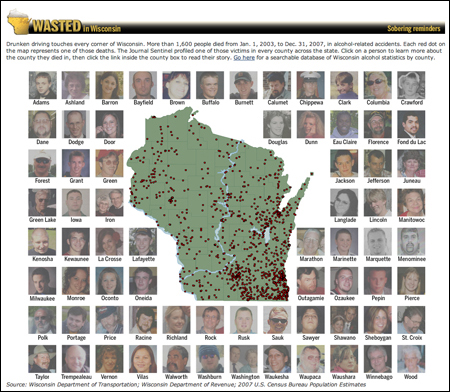

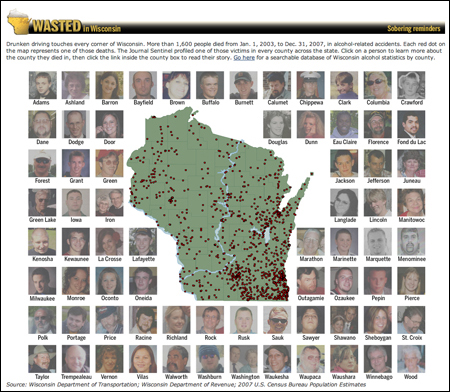

For instance, there was the “Wasted in Wisconsin” series. “We went on a crusade that the drunk driving laws were too lax,” he says. Launched with a personal editor’s note from Kaiser, it included 72 consecutive days of profiles of victims of alcohol-related accidents, from each of the state’s 72 counties.

For the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel's 2008 series "Wasted in Wisconsin," the newspaper ran profiles of 72 people killed by alcohol-related accidents, one from each of Wisconsin's counties.

Then there was the “Empty Cradles” series on Milwaukee’s terrible infant mortality rate, and what could be done about it.

Kaiser says: “I think you’re a little bit on the side of the angels.”

With resources so scarce, a key to watchdog reporting is pre-reporting, he says. “With the size staff we have, if we did a lot of things that the editor cooked up—the big projects that sort of go nowhere—that would be tough,” he says.

And there’s the impact test. At some papers, he says, “Too often it’s: ‘That was a nice big Sunday story that no one could read all of and it didn’t matter.’ ”

Another way in which this watchdog team is unusual is that some projects turn into their own mini-beats.

“A lot of these stories are ongoing stories that once we get onto them, the reporters have stayed with them,” Kaiser says. For instance, there’s one series, called “Side Effects”—about financial ties between doctors and drug companies—that’s been running for almost four years now.

As a result, other daily stories—rather than eerie silence—often follow the publication of a major project.

Kaiser credits his success in part to the newsroom culture of freedom and encouragement that he and managing editor George Stanley have built over the 15 years they’ve worked as a team. The rest of the credit goes to reporters, including experienced staffers who have been around for decades. “Nowadays a short-timer is someone who’s been here 10 or 15 years,” he says. “I’m in no rush to push them out.”

“I want us to be known as a watchdog,” Kaiser says. “Being an editor is a gift and you have a chance to make a difference in your community.”

Dan Froomkin, formerly deputy editor of the Nieman Watchdog website, writes about accountability journalism for Nieman Reports. He is senior Washington correspondent for The Huffington Post.

For Martin Kaiser, editor of the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel since 1997, the answer has been clear: Watchdog journalism is the key to the franchise. So even as the newsroom shrinks, the commitment to being a watchdog grows.

Kaiser could have gone another way. He could have pushed out his most experienced and expensive reporters and prioritized daily stories from Milwaukee’s moneyed suburbs. But the suburban bureaus were one of the many things he threw overboard instead.

“As the newsroom started to get smaller, I really thought we needed to get a lot more focused on what we did and what we didn’t do,” Kaiser says. He concluded: “Let’s do what matters. And the other stuff we aren’t going to do anymore.”

It helped that the Journal Sentinel’s parent company owns a chain of weeklies that are distributed with the newspaper so the small-bore suburban coverage didn’t entirely disappear. But it wasn’t just the bureaus that got cut. “Almost every department is smaller than what it was before,” he says. “You can’t but help having to give up stuff if you go down 70 or 80 people.”

“Do we miss stories? Sure,” he says. “There are profiles and features stories that I’d like to do that we probably don’t get to.” And, he notes: “I’ll admit that even with the suburban weeklies, we’re not covering as much as we used to do.”

But most of the stories they don’t do are “the sort of daily story that doesn’t mean much.”

By contrast, watchdog journalism is way more fun—and, Kaiser thinks, better for connecting with readers. So in 2006, Kaiser started building the Journal Sentinel Watchdog Team, “whose mission,” according to its website “is to work to expose wrongdoing, dysfunction, inequity and injustice and strive to hold accountable those responsible through meticulous case-building and compelling story telling.”

The much-celebrated team now has a dozen members. Their orders: “You’ve got to do stories that matter and you’ve got to have impact.”

“I want people to know that the Journal Sentinel is having an impact, and stirring things up—that you’ve got to see what they have on Sunday in the newspaper. You’ve got to read what they’ve got online,” Kaiser says.

It’s not your typical investigative team in several ways. Its members don’t all sit together in a corner somewhere; they’re physically spread out among the beat reporters. Their stories tend to emerge from reporting, rather than from ideas that come from the top.

And although activism can be a dirty word in journalism these days, Kaiser isn’t afraid to push for change—supported by the facts, and based on widely shared values.

“What I love about it is that in a way it’s the old-fashioned newspaper crusade,” he says. “I think you should stand up for what you believe in and say that’s what you’re doing.”

For instance, there was the “Wasted in Wisconsin” series. “We went on a crusade that the drunk driving laws were too lax,” he says. Launched with a personal editor’s note from Kaiser, it included 72 consecutive days of profiles of victims of alcohol-related accidents, from each of the state’s 72 counties.

For the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel's 2008 series "Wasted in Wisconsin," the newspaper ran profiles of 72 people killed by alcohol-related accidents, one from each of Wisconsin's counties.

Then there was the “Empty Cradles” series on Milwaukee’s terrible infant mortality rate, and what could be done about it.

Kaiser says: “I think you’re a little bit on the side of the angels.”

With resources so scarce, a key to watchdog reporting is pre-reporting, he says. “With the size staff we have, if we did a lot of things that the editor cooked up—the big projects that sort of go nowhere—that would be tough,” he says.

And there’s the impact test. At some papers, he says, “Too often it’s: ‘That was a nice big Sunday story that no one could read all of and it didn’t matter.’ ”

Another way in which this watchdog team is unusual is that some projects turn into their own mini-beats.

“A lot of these stories are ongoing stories that once we get onto them, the reporters have stayed with them,” Kaiser says. For instance, there’s one series, called “Side Effects”—about financial ties between doctors and drug companies—that’s been running for almost four years now.

As a result, other daily stories—rather than eerie silence—often follow the publication of a major project.

Kaiser credits his success in part to the newsroom culture of freedom and encouragement that he and managing editor George Stanley have built over the 15 years they’ve worked as a team. The rest of the credit goes to reporters, including experienced staffers who have been around for decades. “Nowadays a short-timer is someone who’s been here 10 or 15 years,” he says. “I’m in no rush to push them out.”

“I want us to be known as a watchdog,” Kaiser says. “Being an editor is a gift and you have a chance to make a difference in your community.”

Dan Froomkin, formerly deputy editor of the Nieman Watchdog website, writes about accountability journalism for Nieman Reports. He is senior Washington correspondent for The Huffington Post.