The little boy in the photo in the October 14 edition of El Mundo appears below the headline: “A ‘smart’ bomb falls on a Kabul neighborhood.”

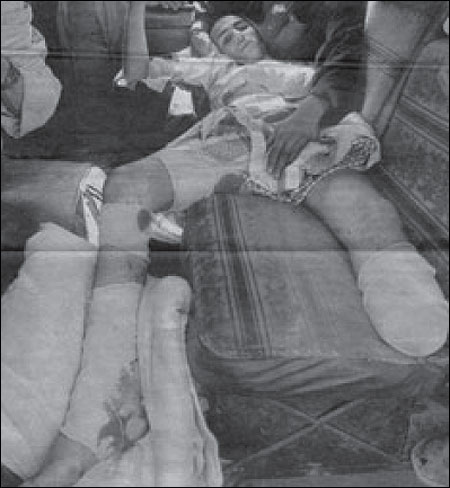

The bloodied Afghan teen with the amputated leg made a living selling ice cream before an American missile hit him. That’s what the caption tells readers who look at the color photo on the front page of Spain’s largest conservative daily, El Mundo, on October 9, two days after bombing of Afghanistan began. “The first collateral damage,” the caption begins sarcastically.

Day two of the “war against terror” and already a quote from the German philosopher Kant appears discretely above the paper’s masthead: “War is evil because it makes more bad men than it kills.”

Cut to the next day’s front page of Diario 16, one of Spain’s oldest national dailies, soon to close despite its recent revamping to capture younger readers. “The U.S. accidentally kills four U.N. employees in Kabul,” the lead headline screams in thick, sans serif type. A picture of “the search for survivors among the ruins” nearly consumes the whole page.

Air strikes continue for a fifth day. Editors at El País, the country’s largest socialist newspaper, slap this headline on their cover: “Taliban say attacks have already caused more than 200 deaths.”

At a time when American leaders are chirping about ending the war before Ramadan, the front pages of Spanish newspapers are filled with photos of Afghan corpses, bloody children, and battered homes. Headlines point to American misfires. Deluxe graphics pay tribute to practically every jet and missile in the U.S. arsenal. Turn the page: Afghan refugees are fleeing with bundles on their backs. Coverage like this makes France’s La Libération, a left-leaning tabloid usually critical of anything America does abroad, look like USA Today.

If Spaniards didn’t know any better, they might not guess that their president, José María Aznar, pledged unconditional support to Bush’s anti-terror coalition. Or that Spain is an important NATO ally with strategic military bases on alert and lending logistical aid since the September 11 attacks. In fact, judging from the repeated barbs at American brutishness—a political cartoon in El Mundo shows two Afghan refugees trekking through the desert beneath a missile—newspaper readers here would probably be surprised to learn that Spanish editorial writers generally consider America’s attack “justified, though of questionable effectiveness.”

So why are newspapers in Spain so determined to show the ugly side of this war on terror? Why are they so quick to portray America as a high-tech bully wreaking havoc on the poor with its array of terrible toys? Why is coverage so critical when Spanish journalists might be expected to welcome any effort to “hunt down” terrorists (to use Bush-speak) since they are favorite targets of the Basque terrorist group ETA, which has claimed almost 1,000 lives in the past 30 years as they’ve tried to gain independence for the Spanish Basque region?

“Our readers tend to be antiwar so any news that spotlights human tragedy, the poor and oppressed, sells papers,” ventures El Mundo’s foreign editor Fernando Múgica, who began his journalism career in 1966. Flashback to the day of the World Trade Center attacks. El País, the same newspaper that would later trumpet news of the 200 Afghan deaths, splashes these words across its front page: “The world on edge in wait for Bush retaliation.” In much smaller type, beneath a picture of the famous, smoking twin towers, comes this addition: “thousands are dead beneath the debris.”

How does one explain the failure to capitalize on this particular human tragedy? “Well, there is a certain sense that America is this conceited empire that acts rashly—cowboy-fashion is the term in vogue since Bush—to protect its pride,” Múgica admits. “When you hear the U.S. was attacked, you think, now who’s going to pay?”

But Spanish coverage is shaped by more than knee-jerk anti-Americanism. For starters, Spanish journalists simply do not consider violence, even U.N.-sanctioned violence, an appropriate way to fight terrorism. Consider: In the late 1980’s, press reports alleged that government ministers had ordered the kidnapping and assassination of several ETA members accused of orchestrating high-profile killings. The ensuing scandal that came out of these accusations not only brought about one conviction—of a government official, not a terrorist—but it also heightened the reputation of a major newspaper (El Mundo) and led to the electoral defeat of the socialist administration.

“Violence only gives more excuses to the terrorists” is the way reporter Luís Angel Sanz sees it. “You have to go to the root of the problem, with legal means. You can’t go bombing the whole world.”

Displays of patriotism also make the press corps shudder. The concept of allegiance to one’s country was so brutally distorted during Franco’s time that, to this day, a waving Spanish flag still symbolizes fascism. It’s no wonder that those bouts of American flag waving after the tragedy make reporters here nervous, fueling snide references to Big Brother.

Then, there is Spain’s reading on America’s foreign policy. In a word, it “stinks.” One hundred thousand Spaniards turned out to protest the Gulf War, and protests against this one in Afghanistan are mounting as well. In press coverage, too, there appears to be a pattern. When the United States bombed Serbia, civilian victims surfaced on the front pages of Spanish dailies along with the usual U.S. gaffes. As Múgica observes, “People think, oh no, those Yankees are screwing up again.” When the Middle East heats up, Israel is portrayed as a U.S. “puppet,” lumped with other monster governments “Made in the U.S.A.” And when readers come across the phrase “the death of Iraqi children,” chances are good they are reading a story about U.S. policy, not about Saddam Hussein.

Finally, Spain has long nurtured a love-hate relationship with the United States. On the one hand, the media depict America as the fountain of all things modern, a model for business, journalism, the arts. Foreign correspondents regularly quote The New York Times and The Washington Post, especially if Bob Woodward has a byline. It’s difficult to find a reporter who doesn’t speak English well enough to translate American wire copy.

Even before the tragedy, American news permeated the press. On September 11, every major Spanish daily put out a special, late edition, five hours after the attacks. Since then, each one has devoted at least 10 pages daily to the crisis. But while the rest of Western Europe (begrudgingly or not) has historically associated America with the defeat of fascism and economic recovery through the Marshall Plan, Spain sneers: “What did you do for us?” Anyone will remind you of President Eisenhower’s pact with their dictator, Franco, in exchange for his cold war support and the installation of American military bases on Spanish soil.

The history books say many actually believed the United States would save Spain from fascism and poverty. The movie “Welcome Mr. Marshall,” required viewing here the way “Citizen Kane” is in America, satirizes those ingenuous hopes and disappointment when the Marshall Plan passed them by. Spain learned the lesson even before Americans did in Vietnam: America isn’t always the good guy. And such mistrust does not fade. As recently as 1982, for instance, former president Felipe González got elected on promises that he would “keep Spain out of NATO.” (He broke his word.) Even though only two U.S. military bases remain here, thousands of residents still protest them now and then.

As setbacks mount in the “war on terrorism” and even U.S. leaders worry about civilian casualties, the Spanish press digs in. “U.S. admits it may never capture bin Laden,” reads a recent front page headline on the ultraconservative paper, ABC. But El Mundo editor Múgica thinks the press hasn’t been critical enough. “Hundreds of people have been detained arbitrarily and remain in custody and we don’t know anything about what happens to them!” he says, outraged.

This media coverage appears to be affecting public opinion. Before the start of the bombing, a survey conducted by Spain’s national statistics center found that as many as 63 percent of the people considered American military response appropriate. A month later, an Internet poll by El Mundo showed support had slipped below 50 percent. Meanwhile, 5,000 people—members of women’s groups, unions, left-wing parties, and immigrant rights associations—took to the streets in Barcelona to protest the war in Afghanistan. This was twice the number that turned out earlier in solidarity for victims of the September attacks.

As an American writing for a Spanish newspaper, I’m accustomed to ritual Bush-bashing and basic skepticism of American foreign policy. I often agree with much of the criticism, but I am finding this coverage, in particular, disturbing and disheartening. From personal experience, I am finding there is indeed a sense among journalists that, as horrible as the tragedy was on September 11, America is finally getting a taste of the world’s suffering. When I mentioned to my editor how scared my mother—living in the United States—is about anthrax, he laughed as if I were joking and shot back, “You’re just not used to having terrorism at home.”

I’ve heard that phrase a lot lately. Several days after the attacks in America, a friend who is a photographer shook his head as he greeted me. It was the first time we’d seen each other since the attacks happened. “America creates its own monsters,” he said, in a knowing tone. He was referring to Osama bin Laden. He knows I am from New York City, but he hadn’t even bothered to ask me if my loved ones were okay.

Dale Fuchs is a feature writer for the national Spanish daily, El Mundo, where she has worked for the past two and a half years. She came to Spain in 1998 on a Fulbright Fellowship for journalists to study coverage of the single European currency and newsroom trends.