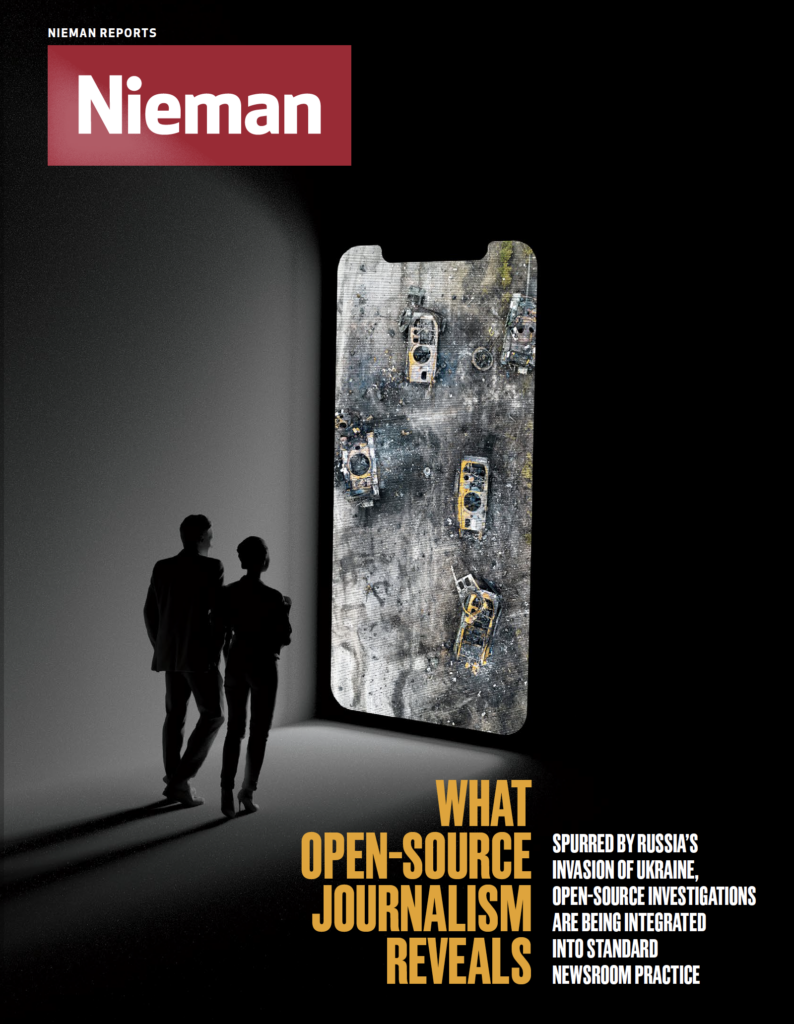

More than nine months into the Russian invasion of Ukraine, the online methods for tracking this war are many and proliferating, including the most obvious source of all: social media networks. From the missile attack on a mall in Kremenchuk to mass graves in Motyzhyn, many reporters have relied on open-source investigations (OSI) — or the use of publicly accessible sources, like satellite imagery and social media posts — to expose Russia’s crimes in this war.

Though the war in Ukraine has been exemplary of OSI, open-source newsgathering is becoming integrated into journalistic practice as a standard reporting technique, particularly at investigative outlets.

Nieman Reports’ Winter 2023 takes a look at how open-source investigations are becoming a mainstay in the digital age, and the newsrooms that have taken the lead in incorporating OSI into their reporting.

John Archibald, NF ’21, discusses his debut as a playwright

I write about life in Alabama. Which means I write about death in Alabama. And issues of life and death — you might have noticed — are complicated.

Especially in Alabama.

Even before the destruction of Roe v. Wade, my home legislatively declared itself a pro-life state, banned assisted suicide, and began incarcerating pregnant women who tested positive for things like THC, often taking their children away once they were born.

It continued to execute people with mental deficiencies, and those sentenced under archaic laws, or on sketchy evidence. It stockpiled people in prisons so overcrowded and dangerous the safest place to be, statistically, is death row.

I’ve been to six executions, including one in the old electric chair they called “Yellow Mama” where a man with an IQ of 69 failed to die on the first jolt. He was killed 19 minutes later, as his father watched.

I write about life and death and hypocrisy. I write and I write and try to tell the stories well. But I wonder if news stories ever make a difference.

That’s where Nieman came in. During my time in Cambridge, I took playwriting courses, and had begun to write a play about the hypocrisies of life and death in the South. It was read at the Harvard Playwrights’ Festival, and people seemed to get it.

I completed that play — “Pink Clouds” — in the months since. It is a play, told through the eyes of a reporter (definitely, surely, probably, maybe not be based on me) who believes he is doing God’s work, but comes to see he cannot save the world if he loses himself or his family. It is about our delusions of certaintly, an exploration of what it means to die, and to exist in a world that seems to value life more than it values lives.

The play is largely about inequality and death — executions, abortions, euthanasia, and other ways people die — and it seeks to underscore the cognitive dissonance of what it means — for some — to be pro-living in a place like Alabama, a state that sanctions death in the name of life.

In September, it was part of a Human Rights Week playwriting festival at Birmingham’s Red Mountain Theatre, and I intend to develop it further.

When I left Cambridge in 2021, I left with one clear goal: I would spend the rest of my life exploring as many different mediums, as many different ways to tell stories, as I possibly could.

If I can’t reach people with facts, I’ll try fiction. If I cannot reach them with columns, I’ll try videos, or podcasts, or plays.

We push ourselves when we try to tell the stories we know in different ways, and it is not always easy. But there is nothing more satisfying — more fun — than to reach people where they are willing to be reached. And to make them feel.