How are great journalists made? Often, it’s pieces of great journalism that help form them, influencing their lives or careers in an indelible way. To celebrate the Nieman Foundation for Journalism’s 80th anniversary in 2018, we asked Nieman Fellows to share works of journalism that in some way left a significant mark on them, their work or their beat, their country, or their culture. The result is what Nieman curator Ann Marie Lipinski calls “an accidental curriculum that has shaped generations of journalists.”

My childhood in Afghanistan coincided with a communist regime under which we had access only to government-sponsored media, including TV, radio, and a couple of newspapers—all tools for government propaganda. My understanding of journalism then was as a profession that works for and praises the government.

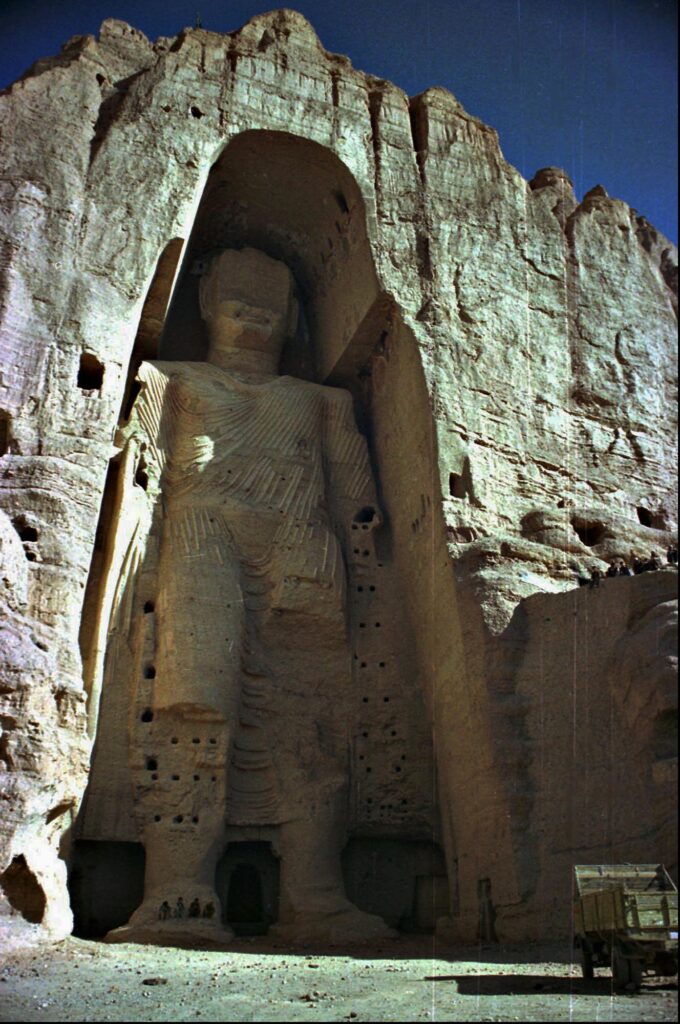

In December 2001, a team from The New York Times traveled to Bamian, Afghanistan’s central highland. The Times reporter Barry Bearak touched the lives of ordinary residents in those mountainous villages; he listened to their stories, their pain, and their struggle to survive. His story was an inspiration to me and an introduction to the independent journalism which I engaged in for more than a decade.

Where Buddhas Fell, Lives Lie in Ruins Too

By Barry Bearak

The New York Times, Dec. 9, 2001

Excerpt

The giant Buddhas perished in this storied valley. For 1,500 years, the two statues stood in their sandstone niches and stared across the rugged plain toward the snowy peaks of the Baba mountains. The Taliban destroyed them last spring, making precise incisions to strategically place the explosives.

But the Buddhas were only the best known and most visible of the Taliban’s victims in this remote region of central Afghanistan. Within months, other terrible crimes were committed here. Ethnic hatred was the grisly wellspring for methodical murder and devastation.

For three and a half years, the Taliban have restricted entry into this battlefield. Only in recent days have outsiders traveled the mine-bedeviled roads to survey the havoc. What they see is scorched earth. Little is left of the hamlets on the heaving single lane west of Bamian except ashes and mud. Decomposed bodies are still being found on the frozen soil.

Barry Bearak © 2001 The New York Times.