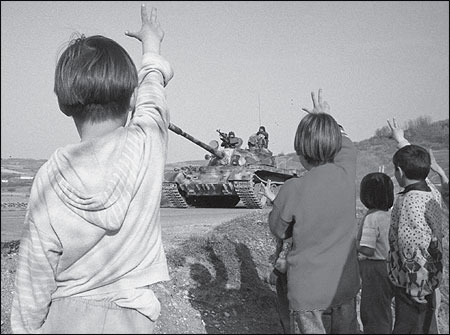

Serbian children flash the Serbian three-fingered symbol at a passing army tank in March as it passes on the road outside of Klina, a town some 50 kms. west of Pristina. Photo by David Brauchli/The Associated Press.

There is no more journalism in Serbia.

Nothing that resembles what is usually understood as being journalism has existed there since the last week of April. That’s when Tomahawk missiles slammed into a number of transmitters of Serbian television, following a deadly attack on the network’s headquarters in which eight people were killed.

But I am not saying that journalism in Serbia is dead because of that. After all, however regrettable the death of civilians, the destruction of Serbian state-run television can hardly be seen as a fatal blow to the freedom of the press. Serbian TV was a powerful and brutal propaganda machine in the service of President Milosevic’s regime.

But Serbia did once have quite a few real journalists. In fact, until recently a number of highly professional dailies, radio and TV stations and magazines flourished there. President Milosevic did his best to strangle that vibrant scene which was so incongruous in the otherwise bleak landscape he created. His henchmen worked hard to persecute Serbian newsmen, but many news organizations still managed to operate. Soon after the first NATO sorties, Serbian police closed down B92, the radio station I worked for, and then nationalized it.

But that wasn’t what killed Serbian journalism, either. In the end, for Serbian journalism to die, it had to commit a suicide.

The story about this suicide is a painful one for me. I know, or I believed that I knew, many of the prominent journalists in Belgrade. Some of them I still consider to be very close friends. But despite knowing those people well, today I can hardly recognize them. Ever since the NATO air strikes began, all those voices of dissent, so important in the years of Milosevic’s oppression, started condoning his policies of confrontation and ethnic cleansing. These are some excerpts from the recent writings of my friends and colleagues who once were the standard-bearers of free thought, independent and professional, masters of critical journalism. The readers will forgive me for not naming names. (If I did, I would feel like a denunciator.) So here are some quotes from Serbian reporters that are not attributed.

“In a savage attack of the NATO aggressors last night the targets were civilians.” (At that time, in the first week of air strikes, no civilian targets were hit.)

“Those who are watching the scenes with Albanian refugees on satellite channels believe that NATO itself considerably contributed to that, that it positioned itself as an ally of the Albanians, and therefore their expulsion is justified to some extent.”

“In Kosovo there are no demolished mosques. Villages are not destroyed, although that could have easily happened, because KLA [Kosovo’s rebel army] was there. The only damaged houses in Pristina [capital of Kosovo] are those struck by NATO bombs.”

Some of our colleagues did not even hesitate to point at those who did not change their views so dramatically. One of them found it necessary to remind the Serbian public (and authorities) that Veran Matic, the Editor-in-Chief of Radio B92, the spiritus movens of unbiased professional journalism in Serbia whose station was closed down and nationalized, failed to start publishing eulogies to Milosevic’s regime. He wrote: “Matic and others are really lucky that the atmosphere in Belgrade is relaxed. The West expected, actually desired, that democratic opposition and journalists be persecuted. They wanted to use that to justify the NATO intervention. But the [Serbian] regime made no such moves.” (Three days later, the leading Serbian publisher was murdered in Belgrade.)

“This [NATO] intervention has nothing to do with morality. The existence of Albanian refugees is used to cover the real aims of this war.”

“The execution of the Serbs is seen [in the West] as a natural right of the superior class and race.”

None of those whom I’ve quoted reacted to the murder of one of our few colleagues who failed to praise Milosevic’s wisdom. Slavko Curuvija, a journalist and the owner of the biggest Serbian daily, stopped publishing the day the air strikes begun. In his only public statement he claimed it was in protest against the NATO intervention, but told his staff that things were going to turn very nasty and that they would not be able to work professionally. So he told them they better stop working altogether. And he went quietly away.

But Milosevic’s family did not forget him. Mira Markovic, Milosevic’s wife, wrote an article which was read out with gusto on Serbian state television, while it was still unscathed by NATO. She reminded the public that Curuvija criticized her and her husband and harbored sympathies for Western democracies. That meant, she went on, that he gloated over NATO attacks and favored them. “He will be punished,” concluded Markovic.

Four days later, two men approached Curuvija as he was entering his apartment and shot him dead in front of his girlfriend. Slavko Curuvija was not criticizing the government during the last days of his life. His sin was simply that he did not join the choir.

My colleagues and friends from B92 are among a very few who did not join it either. I felt good that at least this little group of people still resists. Then I said to myself: “Resists? They are just keeping their mouths shut! So there’s our country in which the highest form of civic courage is to keep quiet.”

In the tiny republic of Montenegro, another unwilling part of Milosevic’s Yugoslavia, journalists are bravely defying his army by writing about all the horrors of Kosovo.

Then it struck me that one could find it easier to stick to principles when one is looking at things from the safety of the United States instead of being caught between the hammer of NATO air power and anvil of the regime responsible for tens, if not hundreds of thousands of deaths. In Montenegro, the government is democratic, and it showed determination to use its police force to protect its citizens from Milosevic’s troops stationed there. In Serbia, journalists are completely on their own.

“What would I be doing,” I asked myself, “if I were there? What would my U.S. colleagues and friends do under similar circumstances? Would I be prepared to risk my life and the safety of my family to wage a battle that seems already lost?” Another friend of mine, also a journalist, managed to flee Belgrade. Ironically, she found refuge in Sarajevo. She wrote to me from there, claiming that while in Belgrade she was more afraid of her neighbors whipped into a nationalistic frenzy by media than of Milosevic’s police.

Again, what would I do? I am not sure that I would show any more courage than my friends and colleagues in these circumstances.

So were all of us so-called independent journalists wrong? Had we been deluding ourselves when we proudly drew a distinction between us, the professionals, and Milosevic’s propagandists on Belgrade television? Actually, they showed far more commitment to journalism, to their work, than did any of us. Spitting at NATO warnings that they would be attacked, they carried on doing what they believed in, fully aware of possible consequences.

However, this may not be a valid comparison. Real journalists are always full of doubts, constantly questioning everything around them, even their own most fundamental beliefs. This inquisitiveness is also the source of our incredible strength, but sometimes it can temporarily result in a pitiful weakness. On the other hand, the casualties buried under the ruins of Belgrade television were propagandists who harbored no doubts. They believed in their leader, followed him unswervingly, and in the end sacrificed their lives for him. We, the journalists, showed less physical courage, but we have survived to be able tomorrow to scrutinize mercilessly all the horrors that will someday be behind us—the responsibility of our politicians and soldiers and even the consciousness of our nation.

Hopefully, we will then find more stamina than we have recently shown and be able to look as mercilessly into our own souls.

Dragan Cicic was a reporter for NIN magazine based in Belgrade, Yugoslavia, from 1991-96, covering wars in Bosnia and Croatia, the crisis in Kosovo, and healthcare issues. From 1997-98 he was Editor for New Media, Radio B92 in Belgrade. He now is in the United States as an M.B.A. candidate at the Wharton School of the University of Pennsylvania. In 1999 Cicic received the Silver Medal at the New York Film Festival as an assistant producer for the BBC documentary “The Serbs’ Last Stand.” The film is about the imminence of war in Kosovo, made before the war began. He is a 1997 Nieman Fellow.