We who work at DoubleTake magazine try not to forget how our publication got to be and why we still want to remember fondly the spoken and written words of William Carlos Williams. In his words, we find his yearning determination to respect mightily the range and authority of American voices, to render them directly, and respond to them as the city doctor he was in Paterson, New Jersey.

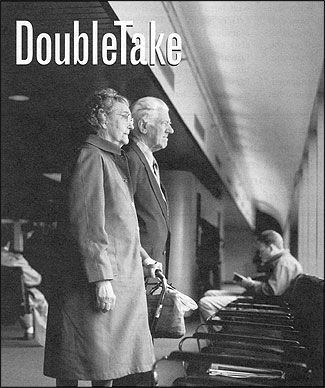

In the pages of DoubleTake, documentary methods are used to convey stories to our readers in much the same way William Carlos Williams employed his many talents as an artist, poet and keen observer—all in the hope of capturing evocative moments from the human experience.

Once, at his home in Rutherford, New Jersey, Williams talked about his medical work while also addressing his passion for the world outside of the hospitals, the clinics, and the sick rooms of urban tenement buildings where he went up and down the stairs on his way to home visits. “I keep my eyes and ears open when I’m sitting with my patients, of course, but lots of times I’m walking the streets, watching what goes on, hearing what people have to say,” he said. “There’s a poetry of everyday life that we all miss—a poetry of words spoken by people as they go through the rhythms of their time spent here in this country of ours, or elsewhere, in other countries, and a poetry of life being enacted, of eyes widened or shut tight, of smiles or grimaces, of bodies bent or put to great and demanding use, a poetry of statement and of sights. The ears (and now the tape recorders) catch the sounds, and the camera catches the views, the human scenes waiting their turn to be noticed, and if someone is paying close attention, waiting to be caught on film—[well, all of that is then] conveyed to the rest of us hungrily curious folks, eager to take in what’s out there.”

An outspoken person, Williams was ever alert to the expressive life of ordinary people and also to the way they presented themselves to one another’s eyes. As an artist and poet, he knew well (and championed the works of) artists such as Charles Demuth, Marsden Hartley, Charles Sheeler. He also had made the acquaintance of Edward Hopper and, once, talking of him, said, “His [Hopper’s] pictures beg for words—he was a genius at showing us what we have to tell! There are silences in his pictures, but not in some of us who look at them, staring long and thinking of what we’d hear, if somehow, through some magic, we were there to listen!” Then Williams, too, was silent before he spoke tersely: “A big challenge, to connect what we see to what we might hear, if we were by some magic where Hopper’s folks are sitting—his ‘people in the sun,’ for instance.”

Williams had in mind a specific oil painting of Hopper’s, done in 1960 and bearing that name. In it, men and women are sitting in chairs, one of them reading a book, the rest gazing at the sky’s all-important, distant daily light. For Hopper, the point was a shared moment of stillness—he was exploring an act of self enhancement through the effort of devoted attention to one of nature’s possibilities. His picture shows people waiting patiently for the warm light that can transform them, that can give them a heightened sense of themselves, as they (and presumably others) scan their sunned selves. But for Williams something else was afoot: “They could be mumbling to themselves or addressing the one sitting near them, the way we sometimes do on a bus or subway, never mind the beach—as in my old refrain: pictures and words, both.”

Williams’ old refrain—“pictures and words, both”—is now our refrain at DoubleTake, a magazine founded expressly to affirm and realize on its pages the reality of what is seen or spoken. Six years ago, photographers and writers who had worked together on documentary projects initiated this magazine in the South. In their work, they’d gotten to know people who were poor, or ones who managed to get by, if not all that well, or who were comfortable indeed, doing “right well,” as Southerners like to say. In founding this magazine, they kept Dr. Williams’ advice in mind, but also looked to others for guidance. In particular, they sought advice from several extraordinary Atlanta journalists—Ralph McGill, Eugene Patterson, and Pat Watters. Each of these men struggled in his own way during the 1960’s to do justice to a changing South’s efforts to end segregation in schools and in communities, or as McGill once put it, “across the board, wherever people come together.”

McGill was the person who first mentioned the idea of a documentary magazine such as DoubleTake. As he put it, “Someday there will be a magazine that will have the space to put on the record all that’s happening, a magazine that brings the stories of those going through ordeals like this one to the attention of the world. We try to do this all the time here [at the (Atlanta) Constitution], but there is so far we can go with a daily newspaper. I often tell my teacher friends that they sometimes underestimate the educational (oh, to be highfalutin’, the cultural) value of newspapers; and even more so of magazines. A magazine allows for longer stories, for continuing stories. A book tells a story, but then it’s published, though the story goes on. In a newspaper, there is today’s story primarily. Magazines can keep at it, tell those stories, give them lots of attention, give the reader the full picture.”

McGill was musing, trying hard to emphasize a newspaper’s capability, but giving us a glimpse of what a magazine like ours could do. Now that DoubleTake exists (with the help of individual and foundation funding), we still recall this early vision of its possibility, just as we recall the words of Dr. Williams—we are minded thereby of our task to create and sustain a place where human stories are told in “the full picture,” in their unfolding and complex dimensions, and where images add essential layers of understanding to the words. “Someday the pictures folks like me take will live side by side with poems and good essays, good fiction,” the photographer Eugene Smith once told a writer for a profile in The New Yorker, a magazine that, then, didn’t publish photographs. Today at DoubleTake photographs have ample room to show aspects of human experience, even as writers do their level best to say what is on their own minds, as well as those of others—a double take, as it were, that we hope does worthwhile, instructive justice to a magazine’s given name.

Robert Coles is an editor at DoubleTake, a teacher at Harvard University, and the author, recently, of “Lives of Moral Leadership.”