Covering Indian Country

As a young reporter at The Rapid City Journal, Tim Giago was seldom allowed to cover stories on the nearby Pine Ridge Indian Reservation where he was raised. As one editor told him, being Native American meant he could not be objective in his reporting. In 1981 he moved back to the reservation to start a community newspaper called the Lakota Times. At that time it was the only independently owned weekly Indian publication in the United States. In this collection of stories, Native Americans and non-natives who tell stories about the lives of Indian peoples talk about their obligation to fairness and the skills they need to live up to this responsibility.

I was returning to a place that I had never really known, the South. It was both my end station and my beginning. A little over a year ago, when I signed on to work on a project called “Voices of Civil Rights,” I had no idea that it would put me in touch with a part of me that had been snuffed out for more than 50 years. The journey started in Washington, D.C., and it would end nine weeks later in Topeka, Kansas.

Sponsored by AARP and The Leadership Conference on Civil Rights, a team of some half dozen reporters worked in three-week shifts, collecting stories and pictures of those unknown foot soldiers of the civil rights movement. I was the project photographer and was lucky enough to go for the entire time. The tour was a symbolic gesture, with the stories and pictures donated to the Library of Congress as the beginning of an archive.

Contrasting Journeys

The earliest memories of my childhood were about the trips to the farm of my maternal grandparents—“going down home,” we called it. We were one of those northern or Midwestern families, in our case Detroit, who every summer would pile in a car and make the trek back to the places of our roots: Georgia, Alabama, Mississippi, Florida. We had family in every stop along the way. But back in the 1950’s, getting there could be pretty hazardous.

Those trips began with my mother standing at the kitchen sink plucking a freshly killed chicken and singing, “Jesus keep me near thy cross,” the sound of running water her only accompaniment. My father had already bought several loaves of day-old Wonder Bread and Fago red pop for the journey. There were blankets, paper towels, and toilet paper for the pit stops beyond Indiana where we were not allowed to stay at motels or use bathroom facilities. It was a picnic. We laughed at the roadside Burma Shave signs and played car tag with friends we met along the way. Years later I learned that these were not chance meetings, but part of a strategy worked out by my father and his friends so that we didn’t have to travel on long stretches of dangerous road alone.

On the Voices tour, we traveled like rock stars in an air-conditioned bus, stocked with food and drink, replete with fax machines, satellite dish, and two wide-screen television sets, front and back, with a drawer full of recent films. And at every stop along the way, there was someone waiting with hotel keys to our rooms.

But the real joys were not the amenities on the bus, but the people I met on the way. They came out in their Sunday best, singing some of the songs my mother sang. They told their stories, shedding them with tears of joy for being able, at last, “to put their burden down.”

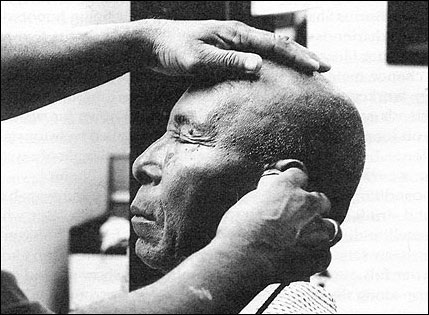

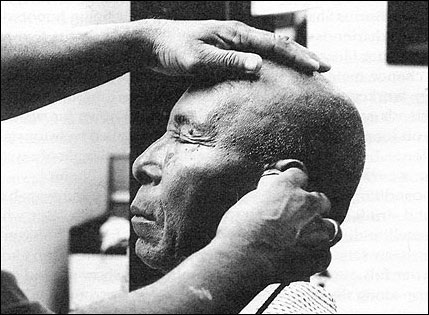

In Birmingham an old man sat in a barber chair like a great warrior king, his ebony face and head freshly shone, while off in a corner his grand nephew told the story of his uncle’s life. These were the men, young and old, who had run the gauntlet of police dogs and cattle prods, who had fought America’s second revolution in order to realize the promises of the first.

In New Orleans a young woman sat with her 100-year-old grandmother while she told her story. She seemed amused that so many people were making such a fuss over her. She had grown old in a white world where people called her by her first name, or “auntie,” and now she was finally being honored.

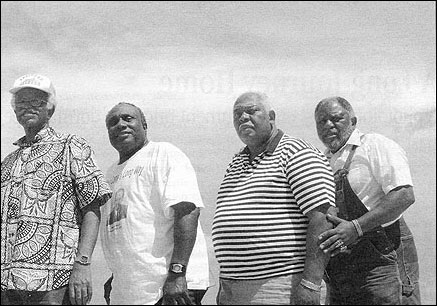

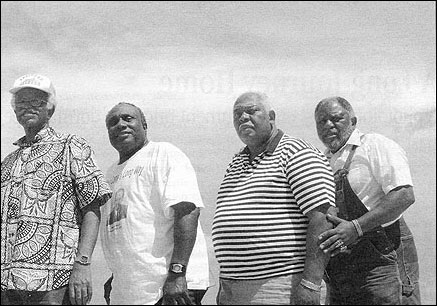

In Baton Rouge, I met the four men who called themselves the “Deacons for Defense.” They looked like the aging frontline of a professional football team. Actually, one was known for rushing a quarterback, but collectively for standing up against the onslaught of a system that set out to destroy them.

At every stop along the way, I met strangers who were my kin. “Boy, where did you say you was from? Who’s you say your people were? Sloan? I don’t know no Sloans, but you show remind me of some Baileys and Borroughs.”

At the beginning of this tour I felt estranged from my southern roots, maybe also a little ashamed. In much the same way that some Europeans wanted to make their children Americans by not speaking the language of the old country, I realized that at some point in my life I turned my back on the birthplace of my parents and, by extension, a part of myself. When I went “down home” again, the South embraced me with open arms, and it was good to be back.

Lester Sloan, a 1976 Nieman Fellow, is a freelance photojournalist based in Los Angeles, California.

"The Deacons for Defense and Justice was formed by African men in Jonesboro and Bogalusa, Louisiana, and Natchez, Mississippi. They were factory workers, farmers, common laborers, fathers, husbands, and church-goers who organized to protect themselves and their communities from the terrorism and oppression of the Ku Klux Klan organizations, White Citizens Councils, and police agencies." — Lester Sloan

"This photo was taken at the Talk of the Town barber shop in the historic 4th Avenue district of Birmingham, Alabama. He was my 'warrior king.'" — Lester Sloan

"This photo of a 100-year-old woman with her granddaughter was taken in New Orleans."

— Lester Sloan

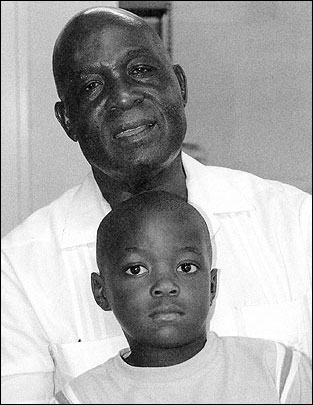

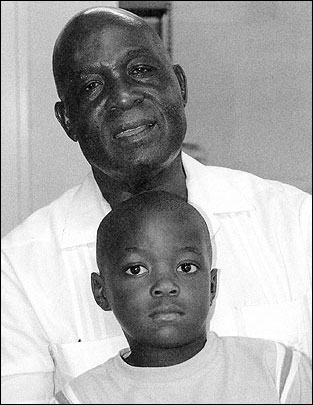

"The photo of this man and his grandson was taken in Summerton, South Carolina."

— Lester Sloan

Sponsored by AARP and The Leadership Conference on Civil Rights, a team of some half dozen reporters worked in three-week shifts, collecting stories and pictures of those unknown foot soldiers of the civil rights movement. I was the project photographer and was lucky enough to go for the entire time. The tour was a symbolic gesture, with the stories and pictures donated to the Library of Congress as the beginning of an archive.

Contrasting Journeys

The earliest memories of my childhood were about the trips to the farm of my maternal grandparents—“going down home,” we called it. We were one of those northern or Midwestern families, in our case Detroit, who every summer would pile in a car and make the trek back to the places of our roots: Georgia, Alabama, Mississippi, Florida. We had family in every stop along the way. But back in the 1950’s, getting there could be pretty hazardous.

Those trips began with my mother standing at the kitchen sink plucking a freshly killed chicken and singing, “Jesus keep me near thy cross,” the sound of running water her only accompaniment. My father had already bought several loaves of day-old Wonder Bread and Fago red pop for the journey. There were blankets, paper towels, and toilet paper for the pit stops beyond Indiana where we were not allowed to stay at motels or use bathroom facilities. It was a picnic. We laughed at the roadside Burma Shave signs and played car tag with friends we met along the way. Years later I learned that these were not chance meetings, but part of a strategy worked out by my father and his friends so that we didn’t have to travel on long stretches of dangerous road alone.

On the Voices tour, we traveled like rock stars in an air-conditioned bus, stocked with food and drink, replete with fax machines, satellite dish, and two wide-screen television sets, front and back, with a drawer full of recent films. And at every stop along the way, there was someone waiting with hotel keys to our rooms.

But the real joys were not the amenities on the bus, but the people I met on the way. They came out in their Sunday best, singing some of the songs my mother sang. They told their stories, shedding them with tears of joy for being able, at last, “to put their burden down.”

In Birmingham an old man sat in a barber chair like a great warrior king, his ebony face and head freshly shone, while off in a corner his grand nephew told the story of his uncle’s life. These were the men, young and old, who had run the gauntlet of police dogs and cattle prods, who had fought America’s second revolution in order to realize the promises of the first.

In New Orleans a young woman sat with her 100-year-old grandmother while she told her story. She seemed amused that so many people were making such a fuss over her. She had grown old in a white world where people called her by her first name, or “auntie,” and now she was finally being honored.

In Baton Rouge, I met the four men who called themselves the “Deacons for Defense.” They looked like the aging frontline of a professional football team. Actually, one was known for rushing a quarterback, but collectively for standing up against the onslaught of a system that set out to destroy them.

At every stop along the way, I met strangers who were my kin. “Boy, where did you say you was from? Who’s you say your people were? Sloan? I don’t know no Sloans, but you show remind me of some Baileys and Borroughs.”

At the beginning of this tour I felt estranged from my southern roots, maybe also a little ashamed. In much the same way that some Europeans wanted to make their children Americans by not speaking the language of the old country, I realized that at some point in my life I turned my back on the birthplace of my parents and, by extension, a part of myself. When I went “down home” again, the South embraced me with open arms, and it was good to be back.

Lester Sloan, a 1976 Nieman Fellow, is a freelance photojournalist based in Los Angeles, California.

"The Deacons for Defense and Justice was formed by African men in Jonesboro and Bogalusa, Louisiana, and Natchez, Mississippi. They were factory workers, farmers, common laborers, fathers, husbands, and church-goers who organized to protect themselves and their communities from the terrorism and oppression of the Ku Klux Klan organizations, White Citizens Councils, and police agencies." — Lester Sloan

"This photo was taken at the Talk of the Town barber shop in the historic 4th Avenue district of Birmingham, Alabama. He was my 'warrior king.'" — Lester Sloan

"This photo of a 100-year-old woman with her granddaughter was taken in New Orleans."

— Lester Sloan

"The photo of this man and his grandson was taken in Summerton, South Carolina."

— Lester Sloan