Editorial Cartoons: The Impact and Issues of an Evolving Craft

Many newspapers have decided not to hire a full-time editorial cartoonist, but instead publish the readily available work of syndicated cartoonists. To explore what impact these decisions and other changing circumstances related to editorial cartoons have on journalism, Nieman Reports asked cartoonists, editorial page editors, and close observers of cartooning to write out of their experiences and share their observations about how the long-time role that cartoons have played in journalism and democracy is being affected. – Melissa Ludtke, Editor

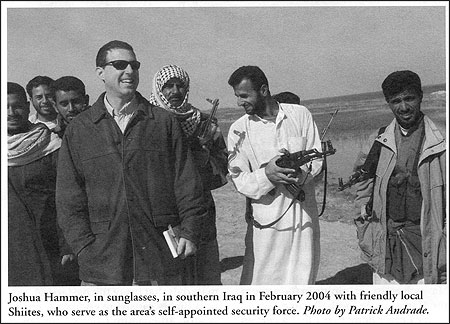

Early last May, I flew into Baghdad from Amman for what I knew would be my last reporting assignment in Iraq for at least one year. Two weeks earlier, Bob Giles had called me at my home in Jerusalem and told me that I had been selected as a Nieman Fellow. The news couldn’t have been more welcome: After nearly four years as Newsweek’s Jerusalem bureau chief, shuttling across the Middle East, I had lived through an exhausting period of turmoil and bloodshed. I was ready to take a break from the field, to spend some quality time with my family, and to reconnect with life in the United States. But first, I thought, I would take one last plunge into Iraq.

As it turned out, the assignment almost turned into my last one. On May 9, Newsweek photographer Robert King and I were captured in the Sunni Triangle city of Fallujah, where we had gone in an ill-considered attempt to make contact with Iraqi insurgents. For eight hours King and I were interrogated, accused of being CIA agents, held in a series of dark cells, and threatened with death. I spent an hour locked in a room with one teenaged captor who kept pointing at me and drawing his finger across his throat. We learned later that our Iraqi drivers and bodyguards, from whom we’d been separated at the start of the ordeal, had been ordered to take ritual baths to prepare for their execution. All along, the Iraqi guerrillas who held us warned us that if the “hardliners”—men loyal to the al-Qaeda-affiliated terrorist Abu Musab al-Zarqawi—found out that we were there, we would certainly be seized and killed on the spot.

We were released only after a Palestinian journalist who knew King, and who happened to be in Fallujah that day, intervened on our behalf and persuaded the insurgents that we were real reporters.

Except for some random gunfire that had crossed my path in Liberia, Rwanda and Macedonia, the experience in Fallujah was the closest I’ve come to being killed in my dozen years as a foreign correspondent for Newsweek. It had a sobering effect on me: It made me realize that some of the risks I took in the course of doing my job were simply not worth taking. It cured me—or so I thought at the time—of any desire to return to the savagery and chaos of Iraq. And it made my decision earlier that spring to spend a year in the ivory tower seem especially well timed.

Our arrival in Cambridge late last August was indeed a satisfying moment. For the first couple of weeks, as I watched the Harvard campus come alive and threw myself into a dizzying cornucopia of lectures, seminars and other events, I was grateful to have put distance between me and the tortured part of the world where I’d spent four years. Yet perhaps not surprisingly, adjusting to the academic life hasn’t been as smooth as I’d expected.

On the positive side, being on sabbatical at Harvard has offered me a much-needed perspective. I’ve found it refreshing and stimulating to be in an environment bubbling over with intellectual ferment. On any given day at Harvard, I can segue from an analysis of management shake-ups at The New York Times to an ethical debate over embryonic stem cell research to a discussion of the relevance of the 1965 Italian film “The Battle of Algiers” to 21st century counter-insurgency. Especially worthwhile has been my contact with the other Nieman Fellows, whose range of backgrounds and nationalities has further catapulted me out of the “tunnel vision” I sometimes experienced in the Middle East. And, of course, there’s the joy of reconnecting with my culture, whether by taking my son trick-or-treating along Oxford Street on Halloween, apple picking in Harvard, Massachusetts, or joining in the wave at the Harvard-Yale football game.

Yet I can’t deny that I feel a certain edginess and a sense of loss as well. I’ve spent a dozen years boarding planes at a moment’s notice, parachuting into crisis zones, observing and writing about societies in tumult. You don’t get that out of your blood so easily. In November I found myself fighting the impulse to fly to Israel to be on hand for the funeral of Yasir Arafat in Ramallah. And despite the nightmarish associations that Fallujah has for me, I can’t say there wasn’t a certain feeling of disappointment that I wasn’t embedded with the U.S. Marines during the dramatic invasion. After investing so much of my life and so much emotion reporting and writing about these places, it has been sometimes difficult to disengage, especially at such critical junctures. But, of course, that’s the fate of the foreign correspondent: The story rarely “ends” when one leaves a place, and one has to find a way of moving on.

My next move remains unclear. At Harvard I’ve spent some of my time

researching my third book, a historical nonfiction narrative related to the great earthquake that destroyed Tokyo and the cosmopolitan port of Yokohama in 1923. I’ve found that burrowing through archives, uncovering obscure primary materials that bring the past to life, can be a highly satisfying endeavor. At the Boston Athenaeum Library I stumbled onto a sheath of wonderfully vivid letters from an American survivor of the disaster that hadn’ t been looked at since they came to the collection in 1924.

Yet I can’t imagine writing books full time; for one thing, only a lucky handful make a living at it. For another, I’ve also realized while doing my research that foreign correspondence remains my first calling. So I’m contemplating a move to Cape Town, where I’ve been offered the post of roving correspondent at large for Newsweek. Harvard has allowed me to take a step back, to savor America and the academic world. But it has also reminded me of what I love most: the thrill and challenge of the reporter’s life.

Joshua Hammer, a 2005 Nieman Fellow, is a foreign correspondent for Newsweek. His Web site is www.joshuahammer.com.