Latino Voices: Journalism By and About Latinos

How is the rapid increase in Hispanic American population affecting communities? What are the economic, social, cultural and educational benefits and hardships brought about by this significant demographic shift? Will the numbers and force of Hispanic voters alter the nation’s political landscape? The questions to be raised and stories to be told vary as greatly as do people portrayed by the word “Hispanic.”

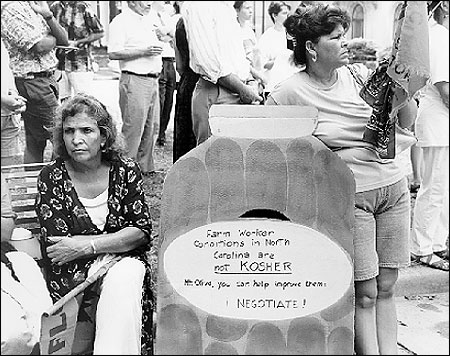

Photo by Chris Johnson.©

Last year, while covering the U.S. presidential election, I definitely entered territory that was unfamiliar to me as a journalist. As a worker in the news business, I am accustomed to asking questions, to seeking information, and to making stories out of what happens to others. Recently, however, I’ve seen some of my colleagues in the Spanish-language media become the story. And it’s happened to me, too. I’ve seen them be interviewed and called for information, just as I have been sought out and questioned by others in the media.

Why have we become a story? It’s because we are caught in the long overdue awakening of the sleeping giant, the slow but certain social and political empowerment of the Latino people living in the United States. As journalists, we are sometimes regarded as people who can speak for all Latinos who, despite being so vast and varied—many with roots planted in this land for generations—have yet to emerge as central participants in the nation’s political arena. Being thrust into this role is difficult and uncomfortable for many journalists, especially those schooled in the traditions of U.S. journalism in which objectivity is considered paramount, and we work to keep distance from our stories.

Journalists are not supposed to be activists. But at times some of us walk a very thin line, particularly when we engage in our craft with some measure of civic and social responsibility.

As an immigrant from Venezuela and a journalist working for La Opinión, a Spanish-language newspaper, I confront very different dilemmas than those of my Latino counterparts who work in mainstream media. I write in Spanish for a readership comprised mostly of immigrants who are not totally proficient either in the language, the culture, or the politics or civic organization of the country in which they now reside. Beyond their need for news about their homelands, our readers often look to us for help in navigating the troubled waters of assimilation and, sometimes, for assistance in defending themselves from difficulties they find along the way.

Back when this “awakening of the sleeping giant” started a few years ago in California, I was covering the immigration beat. At one point, this beat was considered the most important subject for our newspaper. Almost every day I wrote about issues of immigration laws and policies and how they impacted many in the Latino community. I became such an expert in the intricacies of those laws that colleagues joked with me about opening up one of those paralegal services where I could make a better living. My office phone would ring constantly with calls from readers seeking my advice on immigration matters. I often spent much of my time at work trying to steer people away from fraud schemes that offer “amnesty” for a few thousand dollars. I would tell people that there was no such program. This exchange of information with readers became as much a part of my job as reporting and writing.

Instead of feeling conflicted by this role, I often felt great satisfaction at being able to serve people in a way that was a lot more tangible than just writing a story and going home. Sometimes I was pleased to learn that what I did or said make a difference in somebody’s life. Readers would call me with the good news that they had gotten their green card or their citizenship or that they were able to legally bring their spouse and children to this country. That is the best feeling I’ve ever experienced in my few years as a journalist. And these conversations also refreshed my list of story ideas, constantly giving me new angles to report on for the paper.

Something similar happened when Proposition 187 [an initiative to take away the right of undocumented immigrants to attend public schools and receive basic medical care] came along in 1994, and a whole wave of anti-immigrant hysteria emerged out of the political opportunism of California’s then-Governor Pete Wilson. Surrounding this proposition were issues even more divisive than the basic rights that were at risk; the very visible and emotional statewide campaign brought fear to the surface of the debate which revolved around the tremendous population growth of the immigrant community—the so-called “browning” of the state. This initiative passed overwhelmingly in the middle of a recession, but then it failed when it was taken into the courts.

La Opinión, along with other Spanish- language media, took sides in this campaign, and not only on its editorial pages. It was quite clear that we could not be just a passive recorder of information but that we had an obligation to stand on the side of our readership. Most Latinos, including those who were born in this country, understood the racism involved in this political proposition and voted against it.

As a journalist covering the controversy from beginning to end, I always tried to be as fair and objective as I could. But as a reporter for a newspaper that was read by people whose lives would be adversely affected by this inhumane law, I often felt as though I was being pulled and tugged by competing forces in my coverage of this story.

I recall attending a press conference in 1996 after the large wave of new Latino voters reacted to Proposition 187 by helping to put Republicans in the minority of the legislature, and the mainstream media had started to portray Pete Wilson as the main culprit of this political turnaround. I questioned Governor Wilson about his responsibility in having his party now be labeled as anti-immigrant. My question upset him so much that he pointed his finger toward me and said that it was the Spanish-language media that were to blame for the rise in this sentiment.

“You are responsible for spreading false information that I am anti-immigrant. I am only against illegal immigration,” Wilson said. I have to confess that I never felt better about having a politician accuse me of bias. I was biased on this point: I thought Wilson’s electoral strategy was beyond contempt, and I was delighted that he thought of us as having made a difference in letting it be known.

Now a new chapter of Latino empowerment is being written about each day in our newspaper. Millions of immigrants who before were ineligible or unwilling to become naturalized citizens have done so and become registered voters. Presidential candidates—and now a president—are speaking Spanish and want to give interviews to Spanish media. This was unheard of just a few years ago. When I started covering Los Angeles city hall in the early 1990’s, it was hard for me to get most politicians to return my calls, except the very few Latino elected officials. Most mainstream candidates didn’t think it was important to talk to La Opinión or Univision. They figured they couldn’t get very many votes from an interview because our influence reached only to those who spoke Spanish. The conventional wisdom was, “Why bother?” since Spanish-speaking people didn’t or couldn’t vote.

Now that change is occurring so rapidly, the relevance of our newspaper—and of my own work as a journalist—seems directly proportional to the empowerment of the Latino community. Now that the Latino vote is worth fighting for, Latino journalists who work in the Spanish-language media are able to get their questions answered by the very people who, a few years ago, used to ignore us.

I am asked often why I don’t try to find work in the English-language media. I am, after all, proficient in the language and a trained journalist with experience in covering many news areas. The answer is very clear to me: Working where I do, I can make a difference for a community I care about—my own. Yes, the line separating what I do from who I am is sometimes very thin. But that’s an indication to me that I am doing something that matters. And that’s why I became a journalist in the first place.

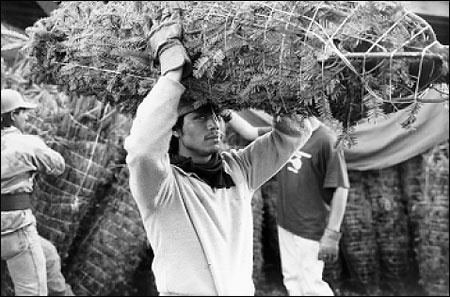

Photo by Chris Johnson.©

Pilar Marrero is political editor for La Opinión newspaper in Los Angeles, California.