Trauma in the Aftermath

Reporting in the aftermath of tragedy and violence, journalists discover what happens when people survive crippling moments of horror. Pushing past what is formulaic and numbing, they find ways to craft stories where the touch is raw and real. In this issue of Nieman Reports, journalists are joined by trauma researchers and survivors themselves in telling their stories in their own voices. We invite you to listen in.

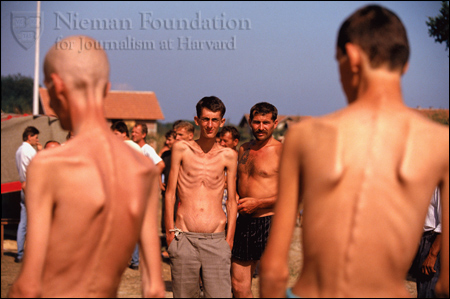

Julia Lieblich, a journalism professor at Loyola University in Chicago, and Esad Boškailo, a psychiatrist and a concentration camp survivor from the Bosnian-Croatian-Serbian conflict, are coauthoring a book about finding meaning after terror. Each spoke about their collaboration on this project during the “Aftermath” conference and vividly described how over time they discovered ways of being able to tell and to hear stories about the horror that Boškailo experienced.

Lieblich: Three years ago a Bosnian man I didn’t know, Esad Boškailo, took a seat in our cramped room at the International Society for Traumatic Stress Studies. I was the lone journalist on a panel on trauma and the media and I was supposed to talk about how journalists should treat their most vulnerable subjects. But after a decade of interviewing survivors in the United States, Asia and Africa, I’d given up pretending that journalists could teach survivors about the aftermath of remembering. An Afghan woman, I explained, could not tell me about the death of her son without enduring weeks of headaches. An amputee in Sierra Leone spoke of a young man yielding a machete only to have nightmares of the attacks. Trauma, he told me, is a special kind of insanity, and storytelling, I believe, is a courageous act [originally rendered as "creative act" due to transcription error].

Esad approached me as soon as the session ended and asked if I wanted to have breakfast with him and his wife the next day. I learned that Esad was both a survivor and a psychiatrist now working in the United States. Fifteen years earlier, he had been liberated from concentration camps and he was finally willing to talk about his ordeal. Would I be interested in coauthoring a book about both our work, he asked, that would benefit survivors of all kinds of trauma? I’m not an impulsive person, but I said yes.

Lieblich explains what happened as they worked to delve into Boškailo’s memories:

Contradictions in accounts were surprisingly rare. More striking were the details Esad had omitted, such as the time men were so thirsty they drank their own urine or how bugs crawled on the skin of prisoners who had not bathed in months.These were no tissues of competing narratives and subjective truth. What mattered were the details that ground true stories—the name of a prisoner who was shot; a guard who brought them figs. The long-term effects of such deprivation were the most devastating to witnesses and perhaps the most compelling evidence of trauma.

We are writing about finding a sense of purpose after trauma, but a close friend of Esad’s told me he could find no meaning after life in the camps. “They take away your soul,” he said.Yet, like Esad, he was willing to take me through those dark nights. The hunger. The sweating. The despair that lasted for months on end. If I was going to write about the first concentration camps in Europe since World War II, he seemed to say, the least I could do was get it right.

Esad Boškailo, a Bosnian refugee who survived 16 months of imprisonment in 10 concentration camps during the Bosnian-Croatian-Serbian conflict, reflects on experiences he’s had with journalists who have approached him to tell his story and what ingredients are necessary for him to find the safety and trust to do so.

Edited excerpts from Boškailo's presentation follow:

I came to the United States directly from the concentration camps in 1994. Somebody said earlier that survivor stories are disorganized, and they are for a reason. I can choose what to talk about. When I talk here about my story it’s difficult. To do so requires safety and trust. If I can give advice to journalists, I suggest it’s all about relationships. One of the first steps in recovery is about reestablishing human relationships and reestablishing how much control you have because during the torture you didn’t have any control. One of the purposes of torture is to take control from someone’s life—control of integrity, identity and humanity.

In the mid-1990’s a Chicago journalist, Michael McCauley, interviewed me for a short piece on NPR. If he’d asked me immediately about my concentration camp experience, I would not have talked to him. Probably. I was very angry after 16 months in those camps. But we talked about my life prior to my trauma, and that I respected.

With me and Julia writing the book, we very carefully built the story in pieces. That was my ability. I couldn’t say the story at once. One of the most important parts is that it was relationship and collaboration; I was able to partially edit the story and say that I don’t want this and I want to expand that. I had that control that I lost completely when I was in the camps.