How are great journalists made? Whatever your image of an inspired origin story, it is unlikely to feature a young reporter sitting on the floor of her apartment reading a weekly from Omaha. But that was Dolly Katz in 1972 when the Omaha Sun broke an investigation of Boys Town, a charity for the homeless and troubled. After months of quiet investigation, the small paper published an eight-page report calling Boys Town a “money machine” that worked harder at growing its endowment than its programs. The Sun’s stories, which came on a tip from new owner Warren Buffett, would win a Pulitzer Prize, the first for a weekly newspaper.

Katz, then a young reporter at the Detroit Free Press, was inspired by the story out of Omaha, some of the first investigative journalism to carefully examine charitable spending. The work “demonstrated that the main ingredients for good journalism are a supportive publisher, energetic and determined reporters, and a commitment to exploring the full story,” she recalls. “The series was not a ‘gotcha’ moment; it was nuanced and fair.” More than four decades later, the 1977 Nieman Fellow remembers still the impact it had on her.

Great journalists are formed by great journalism, excellence being a catalytic force for good. For the Nieman Foundation’s 80th anniversary, we asked alumni for examples of journalism that influenced them, their beat, their country, or their culture. Katz and others responded with 80 extraordinary stories, photos, books, podcasts, cartoons, and more—the elements of an accidental curriculum that shaped generations of journalists and their work, in some cases Nieman-to-Nieman. Former curator Bill Kovach, NF ’89, writes that after reading I.F. Stone’s crusading reporting he abandoned plans to become a marine biologist. Some years later, Kovach’s influential book “The Elements of Journalism,” co-authored with Tom Rosenstiel, would in turn be discovered by Indonesian reporter Andreas Harsono, NF ’00. Harsono would help to arrange its translation and the book is now required reading in many journalism schools in the region, “helping to nurture journalists in Indonesia.”

Among the joys of reading through these accounts are the vivid recollections from Niemans of where they were when they discovered the work that would change them. So much media is disposable, designed to serve us for a day, an hour, a moment as we scramble to the next breaking news alert. But these encounters had a rare indelible quality—journalism that endured.

Alison MacAdam, NF ’14: “I still remember where I was when I heard this story. It was night. I was driving alone—the best time to listen to the radio.”

Georg Diez, NF ’17: “I was sitting in a smelly hotel room somewhere in Vietnam, it was the early ’90s and I had met these lovely Israelis whom I joined on the path up North. I was lonely, I wasn’t happy. And I read Michael Herr’s ‘Dispatches.’”

Nina Bernstein, NF ’84: “I was then a reporter for New York Newsday, and I remember striding across Midtown Manhattan to the newsroom clutching the paper, galvanized by the explosive headline—‘The Death Camps of Bosnia.’”

Christopher Weyant, NF ’16: “I was a teenager prowling around in the back of a dusty used bookstore searching for cartoons. Sandwiched in the art section were two small shelves that held books of cartoons…It was there I stumbled upon a small collection of [Pat] Oliphant’s work, covering the first term of the Reagan administration. I fell in love.”

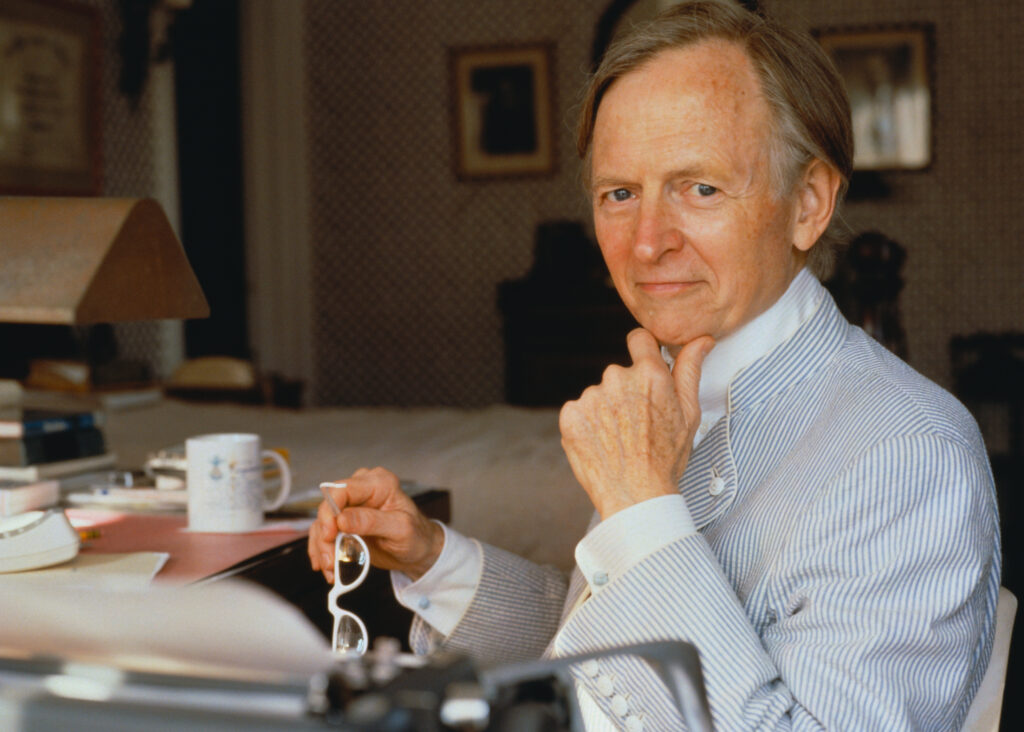

Alex S. Jones, NF ’82: “It was the mid-’60s and I was in college and … [Tom Wolfe] was coming to speak… I was mildly interested as I had some writing aspirations, and almost without thinking I showed up to hear what he had to say. …It was life-changing because his writing was so new, so different, so not like anything else journalistic!”

The discoveries weremore than just memorable and for many signaled the start of professional transformation. It’s as if in reading a book, viewing a documentary, or seeing a photograph, a threshold was crossed and there was no retreat. For some, change was immediate. Anita Harris, NF ’82, saw “Harvest of Shame,” the legendary Edward R. Murrow documentary on migrant workers, and recounts, “That night, I resolved to become a journalist.” For others, exposure to new forms revealed dramatic new possibilities.

“Growing up in Nepal under the autocratic monarchy I did not know that journalists could tell stories about underdogs,” writes Subina Shrestha, NF ’17. Then, while studying in India, she came upon Palagummi Sainath’s “Everybody Loves a Good Drought” and her world shifted. “I had never seen a journalist with such passion for finding stories of the people who had been systematically silenced… I realized that I did not even know my country.”

Reading books by Cahuilla Indian editor and author Rupert Costo, recalled Tim Giago, NF ’91, “made me understand more deeply that we, the Indian People, had to write our own books in order to bring out the parts of American history that were suppressed.”

Great journalists are formed by great journalism, excellence being a catalytic force for good

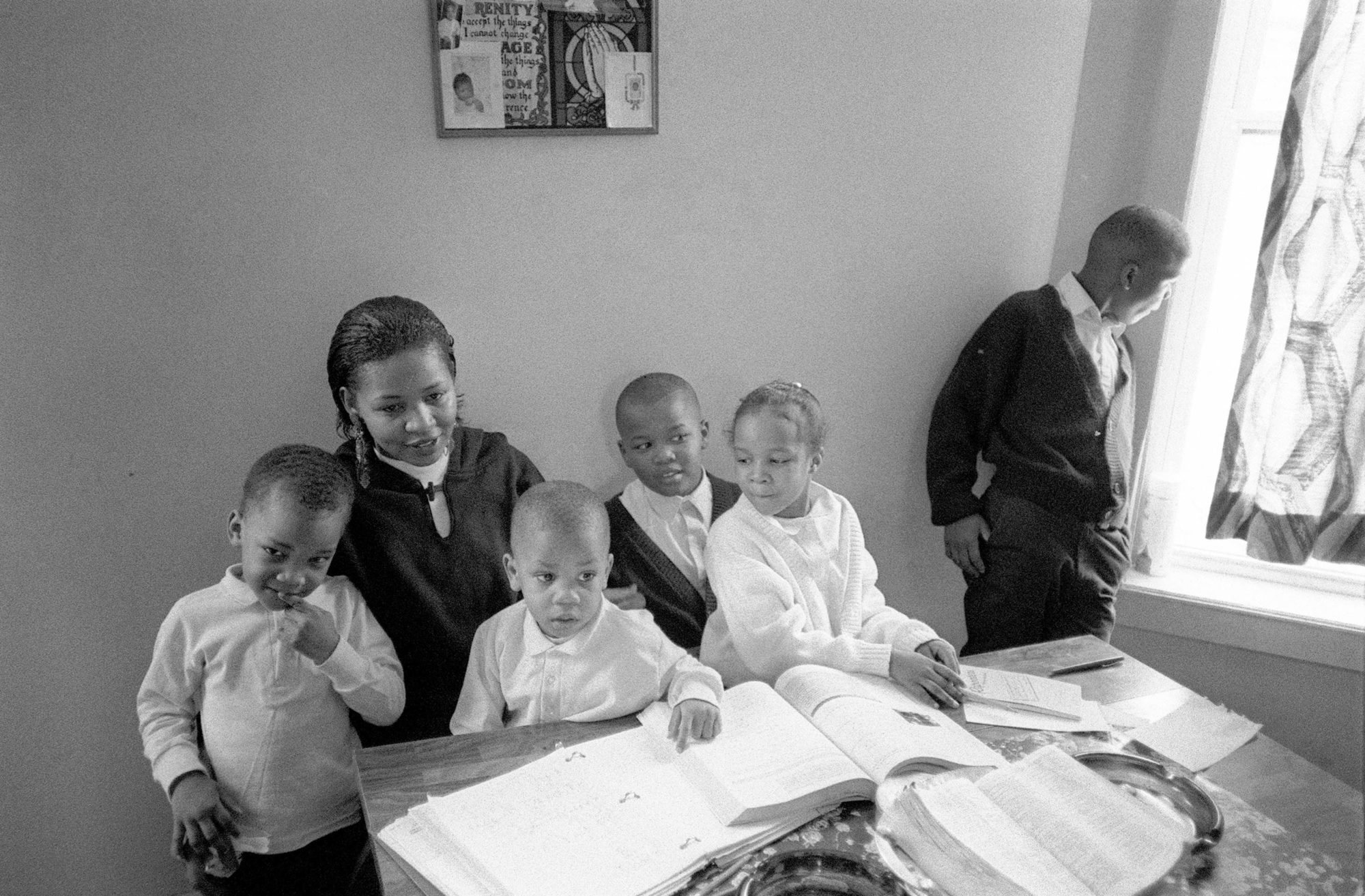

Lolly Bowean, NF ’17, returns “over and over” to an Isabel Wilkerson profile of 10-year-old Nicholas on the South Side of Chicago as a guide to navigating her own journalism in that city. “I read and re-read Wilkerson’s profile repeatedly not only because it is a great blueprint, but it reminds me why I do this work: to amplify the voices of the unheard and to help communities better understand each other.”

Gabe Bullard, NF ’15, was on his Nieman fellowship, feeling “stuck” after years working with audio, when he heard an explosive new podcast by Sarah Koenig and with it a call to action. “When ‘Serial’ blew up, it was like a giant voice granting permission to do something different,” recalls Bullard, “and challenging all us audio journalists to make something great.”

Five years ago, as Nieman marked its 75th anniversary, the explosion of #MeToo stories had yet to be published and the internationally networked Panama Papers investigations had not been written. It is also true that “fake news” was not a weapon wielded from high office while conspiracy web sites masquerading as news found succor.

Reporting moves fast as do its detractors, both with the power to persuade. Somewhere, future journalists are paying attention.