I didn't set out to be a journalist. When I went on paternity leave from my doctoral program for the spring 2003 semester, I planned to write a dissertation—with my baby son strapped to my chest—about Gertrude Stein's impact on American poetry. But other interests took over. In time, my impulse to reconnect with my father's life in the civil rights movement gave me a new role to play—as a blogger, then journalist—unearthing stories from his time, untold until now.

My father Paul A. Greenberg died in 1997. For the next five years, I spent what extra time I had researching his life. This meant collecting recordings and chasing down details about the life of jazz trumpeter Frankie Newton, my father's dear friend and mentor, and exploring the times in the 1950's and '60's when my father was involved with the labor and disarmament movements and as special assistant to Martin Luther King, Jr. with the civil rights movement in the Southern Christian Leadership Conference.

It didn't take long for Stein—and my academic ambitions—to be eclipsed by this expanding journey into my dad's past. By 2004, I had accumulated thousands of pages of Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) documents from Freedom of Information Act requests. I had also begun reading blogs. That February, one of my favorite bloggers, the pseudonymous Jeanne D'Arc, posed a series of questions and shared links to what she was reading about the ouster of Haiti's president, Jean-Bertrand Aristide. As her questions evolved into an analysis of the developing situation, it struck me that blogging offered a different structure than writing a book or for a magazine. With its open-ended and incremental format, a writer could present the process of making sense of new information; it was a perfect way for me to explore what I was learning about my father.

Soon, my blog, Hungry Blues, was born.

Visibility and Community

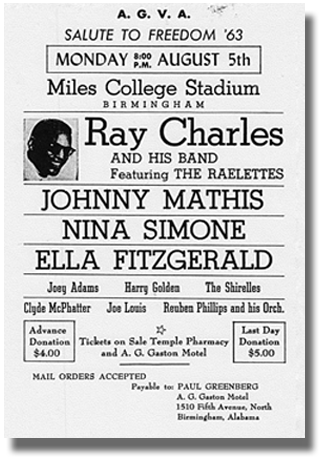

It wasn't long before one of my father's colleagues, Robert Adamenko, found a blog post I'd written about the August 5, 1963 benefit concert my father helped organize to raise money for locals to attend that summer's March on Washington. Held on the campus of the historically black Miles College, just outside of Birmingham, Alabama, where no venue would allow an integrated civil rights movement event, the show was headlined by Ray Charles, Nina Simone, Johnny Mathis, and Ella Fitzgerald.

"Ben, I came across Hungry Blues online and my past was coming out of my head, what a wonderful time I had with Paul in Birmingham. Your dad was my mentor and friend," Adamenko wrote in his e-mail to me. He also sent me negatives of photos he took of the show.

My first year of blogging in 2004 also led to my first investigation, a case that still haunts me. That summer I noticed someone on a listserv for civil rights movement veterans posting a link to a brief article in the Montgomery Advertiser about a 29-year-old black man named Winston "DeRoyal" Carter, who on August 13 had been found dead, hanging from a tree on County Road 65 in Tuskegee, Alabama.

I sensed that the person on the listserv knew more about the story than what had been published. She and I began corresponding. Turns out that her husband, also a veteran civil rights activist, had gone to Tuskegee to investigate. Despite the suspicious circumstances, the case was dismissed as a suicide even before the police investigation was complete and autopsy findings had been disclosed. The news needed to spread beyond Alabama or Carter's story would soon be forgotten.

Recalling how bloggers had drawn national attention to United States Senator Trent Lott's racist demagoguery in 2002, I reached out to about 20 bloggers. Soon this story darted around the Internet. One of my blogger friends had gone to school with Carter. A member of Carter's family contacted me and we began sharing information. I filed a public records request for the autopsy report. But as local officials stonewalled Carter's family members, they, in turn, pulled back from talking with me. With no resources for travel, no newsroom behind me, and no access to sources, I had to step away from the case.

More and more I was looking not just at my father's story but also at the unfinished business of the civil rights movement. In June 2005, after 41 years of impunity, notorious Klansman and preacher Edgar Ray Killen was charged with the June 21, 1964 murders of civil rights workers James Chaney, Andrew Goodman, and Michael Schwerner. Veterans of the civil rights movement had taken notice of my blogging about the case and invited me to the annual memorial service in Mississippi.

As I made plans for the trip, I called my mother to tell her.

"You're not going," she said.

Often when I'd ask her about my father's past, she said things like, "I was raising your two sisters and keeping the home together. I couldn't focus on the details of what he was doing."

I saw this was only partly true. The truth was that she had been traumatized. My father went off to Alabama to fight in the civil rights wars. Back home, we were the freedom soldier's family suffering the uncertainty of whether he would ever make it back home. Now, nearly five decades later, I went to Mississippi, saw life in the Deep South, confronted silence, fear, resistance. There was no question I'd make it back home—and no question that the region's history had me in its grasp and that I would return.

Blogger to Journalist

One of the first bloggers to encourage my work about my father was College of New Jersey journalism professor Kim Pearson, blogging then as Professor Kim. In October 2005, her blog led me to a post by Spencer Overton on www.blackprof.com about the Federal Emergency Management Agency's refusal to give the Louisiana secretary of state the temporary addresses of Hurricane Katrina evacuees. The official wanted to mail them absentee ballots for upcoming elections in New Orleans.

The implications were staggering. Most of the estimated 300,000 evacuees were black, and there was no clear way to get them absentee ballots. A friend helped me to pitch this story to In These Times, and with its publication I became the first in the national press to identify, investigate and analyze the black voting rights crisis facing these Katrina survivors. Several months later my article was cited in Congressional testimony before the House Judiciary Committee in support of the continuation of the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

By then, I was a guest editor for the special issue Dollars & Sense magazine did in the spring of 2006 about the Gulf Coast after Hurricane Katrina. I hadn't planned on going there until Gayle Tart, a black attorney in Gulfport, Mississippi, insisted the only way I could understand the Mississippi situation well enough to cover it was to come there and see it for myself. During that week in Mississippi, Tart and other local activists guided me through the region and helped me set up interviews with more than 20 storm survivors, primarily blacks. It's disappointing—though perhaps sadly predictable—to realize that my article along with interviews I did with two Mississippi Gulf Coast activists are still among the few comprehensive news reports describing post-Katrina life for blacks in Mississippi. While there, I also launched the Dollars & Sense Blog to provide updates from the Gulf Coast; the blog remains a strong hub of the magazine's online presence.

In the summer of 2007, I returned to Mississippi to look into violence that had taken place near Woodville in the southwest part of the state. After I interviewed an NAACP official, a black woman in her early 70's who owned a shop in the town center stopped me on the street. "You a reporter?" she asked. Before long, she and her husband were sharing stories of violence against blacks in Woodville in the '50's and '60's. They asked if I had ever heard of Man Walker whose given first name was Clifford or Clifton. He was shot in his car on Poor House Road and they thought his children lived nearby in Louisiana.

Since I was on my way to Hattiesburg to do research in the McCain Archives at the University of Southern Mississippi, I couldn't stick around to learn more. Yet at the archives, I found a number of Mississippi Highway and Safety Patrol reports on the Clifton Walker case. The reports were riveting. I had to investigate.

I've located a number of Walker's family members and have been working closely with three of his children since 2008. One daughter, Catherine, has joined me in questioning those with possible involvement in her father's murder. On one occasion there was a surprising moment of reconciliation between Catherine and a member of a white Woodville family. Walker's murder had allegedly been planned at this family's truck stop, and at the end of the interview with the elderly business owner and his daughter, Walker and the other daughter hugged. Catherine had not expected to meet whites from Woodville willing to talk about the murder. This small but significant step toward the closure that she and her siblings need gave us a taste of what might be possible for her family and for this small backwoods Mississippi community that is still largely committed to silence and to protecting murderers.

In August 2010, just five days after I blogged about the FBI's failure to contact Walker's children, an agent assigned to the case contacted me to ask for help in reaching family members. Though the FBI reached Catherine in 2010, more than a year later no meeting with the Walkers has yet been scheduled.

Through my association with the Civil Rights Cold Case Project I've found steady camaraderie, advice and information from my colleagues, as well as some funding, as I've worked from Boston. Even before publishing my feature-length story about Walker's murder, my blog posts, social media presence, and the visibility of my work on the project's website have brought attention to an otherwise little-known, 47-year-old murder case, now actively under investigation by the FBI with a possibility of being solved.

Moving along this path I started down in 2003, I couldn't know then where it would take me nor foresee what would happen when stories shadowed by silence are brought into the light.

Ben Greenberg is a freelance writer and photographer based in Boston. He blogs at hungryblues.net.

My father Paul A. Greenberg died in 1997. For the next five years, I spent what extra time I had researching his life. This meant collecting recordings and chasing down details about the life of jazz trumpeter Frankie Newton, my father's dear friend and mentor, and exploring the times in the 1950's and '60's when my father was involved with the labor and disarmament movements and as special assistant to Martin Luther King, Jr. with the civil rights movement in the Southern Christian Leadership Conference.

|

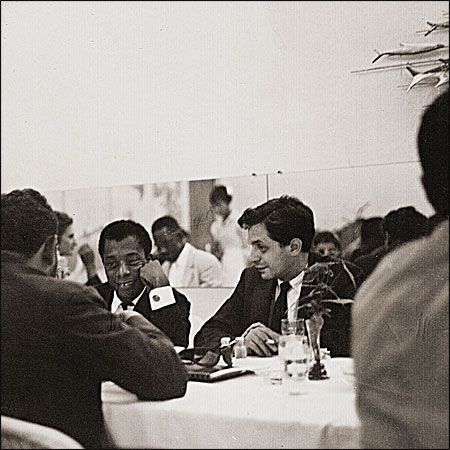

| James Baldwin, left, and Paul A. Greenberg helped with the 1963 Salute to Freedom benefit concert near Birmingham, Alabama. Photo by Robert Adamenko. |

It didn't take long for Stein—and my academic ambitions—to be eclipsed by this expanding journey into my dad's past. By 2004, I had accumulated thousands of pages of Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) documents from Freedom of Information Act requests. I had also begun reading blogs. That February, one of my favorite bloggers, the pseudonymous Jeanne D'Arc, posed a series of questions and shared links to what she was reading about the ouster of Haiti's president, Jean-Bertrand Aristide. As her questions evolved into an analysis of the developing situation, it struck me that blogging offered a different structure than writing a book or for a magazine. With its open-ended and incremental format, a writer could present the process of making sense of new information; it was a perfect way for me to explore what I was learning about my father.

Soon, my blog, Hungry Blues, was born.

Visibility and Community

It wasn't long before one of my father's colleagues, Robert Adamenko, found a blog post I'd written about the August 5, 1963 benefit concert my father helped organize to raise money for locals to attend that summer's March on Washington. Held on the campus of the historically black Miles College, just outside of Birmingham, Alabama, where no venue would allow an integrated civil rights movement event, the show was headlined by Ray Charles, Nina Simone, Johnny Mathis, and Ella Fitzgerald.

"Ben, I came across Hungry Blues online and my past was coming out of my head, what a wonderful time I had with Paul in Birmingham. Your dad was my mentor and friend," Adamenko wrote in his e-mail to me. He also sent me negatives of photos he took of the show.

My first year of blogging in 2004 also led to my first investigation, a case that still haunts me. That summer I noticed someone on a listserv for civil rights movement veterans posting a link to a brief article in the Montgomery Advertiser about a 29-year-old black man named Winston "DeRoyal" Carter, who on August 13 had been found dead, hanging from a tree on County Road 65 in Tuskegee, Alabama.

I sensed that the person on the listserv knew more about the story than what had been published. She and I began corresponding. Turns out that her husband, also a veteran civil rights activist, had gone to Tuskegee to investigate. Despite the suspicious circumstances, the case was dismissed as a suicide even before the police investigation was complete and autopsy findings had been disclosed. The news needed to spread beyond Alabama or Carter's story would soon be forgotten.

Recalling how bloggers had drawn national attention to United States Senator Trent Lott's racist demagoguery in 2002, I reached out to about 20 bloggers. Soon this story darted around the Internet. One of my blogger friends had gone to school with Carter. A member of Carter's family contacted me and we began sharing information. I filed a public records request for the autopsy report. But as local officials stonewalled Carter's family members, they, in turn, pulled back from talking with me. With no resources for travel, no newsroom behind me, and no access to sources, I had to step away from the case.

More and more I was looking not just at my father's story but also at the unfinished business of the civil rights movement. In June 2005, after 41 years of impunity, notorious Klansman and preacher Edgar Ray Killen was charged with the June 21, 1964 murders of civil rights workers James Chaney, Andrew Goodman, and Michael Schwerner. Veterans of the civil rights movement had taken notice of my blogging about the case and invited me to the annual memorial service in Mississippi.

As I made plans for the trip, I called my mother to tell her.

"You're not going," she said.

Often when I'd ask her about my father's past, she said things like, "I was raising your two sisters and keeping the home together. I couldn't focus on the details of what he was doing."

I saw this was only partly true. The truth was that she had been traumatized. My father went off to Alabama to fight in the civil rights wars. Back home, we were the freedom soldier's family suffering the uncertainty of whether he would ever make it back home. Now, nearly five decades later, I went to Mississippi, saw life in the Deep South, confronted silence, fear, resistance. There was no question I'd make it back home—and no question that the region's history had me in its grasp and that I would return.

Blogger to Journalist

One of the first bloggers to encourage my work about my father was College of New Jersey journalism professor Kim Pearson, blogging then as Professor Kim. In October 2005, her blog led me to a post by Spencer Overton on www.blackprof.com about the Federal Emergency Management Agency's refusal to give the Louisiana secretary of state the temporary addresses of Hurricane Katrina evacuees. The official wanted to mail them absentee ballots for upcoming elections in New Orleans.

The implications were staggering. Most of the estimated 300,000 evacuees were black, and there was no clear way to get them absentee ballots. A friend helped me to pitch this story to In These Times, and with its publication I became the first in the national press to identify, investigate and analyze the black voting rights crisis facing these Katrina survivors. Several months later my article was cited in Congressional testimony before the House Judiciary Committee in support of the continuation of the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

By then, I was a guest editor for the special issue Dollars & Sense magazine did in the spring of 2006 about the Gulf Coast after Hurricane Katrina. I hadn't planned on going there until Gayle Tart, a black attorney in Gulfport, Mississippi, insisted the only way I could understand the Mississippi situation well enough to cover it was to come there and see it for myself. During that week in Mississippi, Tart and other local activists guided me through the region and helped me set up interviews with more than 20 storm survivors, primarily blacks. It's disappointing—though perhaps sadly predictable—to realize that my article along with interviews I did with two Mississippi Gulf Coast activists are still among the few comprehensive news reports describing post-Katrina life for blacks in Mississippi. While there, I also launched the Dollars & Sense Blog to provide updates from the Gulf Coast; the blog remains a strong hub of the magazine's online presence.

In the summer of 2007, I returned to Mississippi to look into violence that had taken place near Woodville in the southwest part of the state. After I interviewed an NAACP official, a black woman in her early 70's who owned a shop in the town center stopped me on the street. "You a reporter?" she asked. Before long, she and her husband were sharing stories of violence against blacks in Woodville in the '50's and '60's. They asked if I had ever heard of Man Walker whose given first name was Clifford or Clifton. He was shot in his car on Poor House Road and they thought his children lived nearby in Louisiana.

Since I was on my way to Hattiesburg to do research in the McCain Archives at the University of Southern Mississippi, I couldn't stick around to learn more. Yet at the archives, I found a number of Mississippi Highway and Safety Patrol reports on the Clifton Walker case. The reports were riveting. I had to investigate.

I've located a number of Walker's family members and have been working closely with three of his children since 2008. One daughter, Catherine, has joined me in questioning those with possible involvement in her father's murder. On one occasion there was a surprising moment of reconciliation between Catherine and a member of a white Woodville family. Walker's murder had allegedly been planned at this family's truck stop, and at the end of the interview with the elderly business owner and his daughter, Walker and the other daughter hugged. Catherine had not expected to meet whites from Woodville willing to talk about the murder. This small but significant step toward the closure that she and her siblings need gave us a taste of what might be possible for her family and for this small backwoods Mississippi community that is still largely committed to silence and to protecting murderers.

In August 2010, just five days after I blogged about the FBI's failure to contact Walker's children, an agent assigned to the case contacted me to ask for help in reaching family members. Though the FBI reached Catherine in 2010, more than a year later no meeting with the Walkers has yet been scheduled.

Through my association with the Civil Rights Cold Case Project I've found steady camaraderie, advice and information from my colleagues, as well as some funding, as I've worked from Boston. Even before publishing my feature-length story about Walker's murder, my blog posts, social media presence, and the visibility of my work on the project's website have brought attention to an otherwise little-known, 47-year-old murder case, now actively under investigation by the FBI with a possibility of being solved.

Moving along this path I started down in 2003, I couldn't know then where it would take me nor foresee what would happen when stories shadowed by silence are brought into the light.

Ben Greenberg is a freelance writer and photographer based in Boston. He blogs at hungryblues.net.