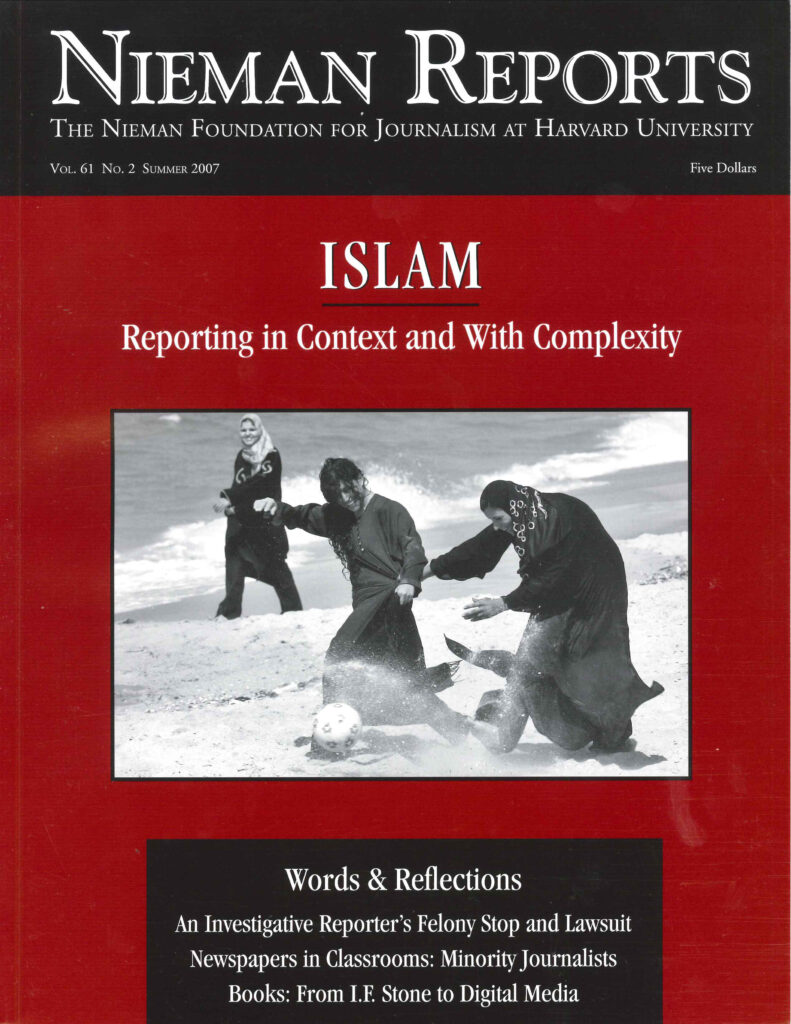

Iraqis seek cover as British tanks open fire on Iraqi Army positions in the outskirts of Basra. March 30, 2003. Photos by Anja Niedringhaus.

During this 2003 battle for Basra, the second largest city in Iraq, the outskirts of the city saw heavy fighting. (Coalition troops eventually took the city on April 6th.) Even the International Red Cross wasn't allowed into the city's center. In a lull in the fighting, civilians sought refuge by leaving Basra. I had crossed from Kuwait earlier that month, hidden in a Kuwaiti fire brigade truck that had been sent to help extinguish the burning oil fields around Basra. Once in Iraq, I covered the fall of the city with my Associated Press colleagues. I remember watching a fierce battle around the city's university. Shells started to land nearby, and most journalists left the scene. I had just put on my bulletproof vest when another shell landed so close to me that it injured three of my colleagues. I escaped with bruises and was able to drive them to safety in our Jeep, even though it was also hit, and two of its four tires were flat. One of my colleagues, a Lebanese cameraman, had shrapnel close to his heart and was immediately operated on by a British Army doctor in a makeshift tent. We were flown out to Kuwait for further treatment. Three days later I returned to Iraq in a rented Jeep from Kuwait. I called it "Toyota Sheraton," and it became my home until I reached Baghdad six days later.

Marines from the 1st Division raid a house in the Abu Ghraib district of Baghdad, Iraq. November 2, 2004.

For the first time I was embedded when I joined a unit of Marines—Lima Company—weeks ahead of their major assault on Fallujah. The occupation of Iraq from a soldier's point of view was very different. I had only worked with Iraqis before, getting to know their families, and tried to understand the situation through their eyes. What struck me most was how young the Marines were—just out of school, young boys. One day I joined them on a house raid in the Abu Ghraib district of Baghdad. It was the house of a local city council chairman. The Marines started to search for weapons while the women and children took refuge in the kitchen. I sensed that my presence during the raid—since I wasn't wearing a military uniform and being a woman—helped the women and children feel safer. Perhaps they felt that a nonmilitary person, a journalist, would help keep them safe. I felt only sadness and embarrassment when the Marines found an old, rusty, small gun in the garden and arrested the city council chairman.

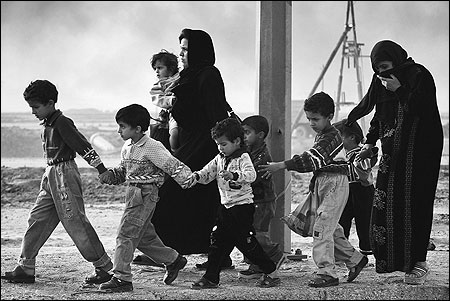

A head of a child's doll is mounted on a stick at a checkpoint leading into the heavily guarded city of Fallujah, Iraq. February 6, 2005.

Two months after a major assault on Fallujah, civilians returned to the city. They faced several checkpoints set up by U.S. Marines and the Iraqi Army. After covering the initial attack, I embedded again with Lima Company to see what had happened to the city. Very few civilians had returned. Troops surrounded the area, and heavy weaponry was still in place. Lima Company's base was a hospital on the outskirts of the city. I was glad to see the Marines I'd come to know again. The assault had been difficult and dangerous, and a bond had grown between us. I wouldn't say they were friends, but I cared about them.

Bosnian Muslim men attend a funeral ceremony at sunset to be more protected from sniper fire. Sarajevo. July 20, 1993.

Sarajevo was besieged for more than four years with sectarian violence dividing the city into Muslim and Serb-orthodox parts. Shelling and sniper fire from surrounding buildings became a kind of normality. Many times funeral ceremonies came under sniper fire with people taking cover in ditches next to coffins. At this funeral, three Muslim family members—two brothers and their mother—were to be buried. The men arrived at sunset and placed the coffins on the street next to Sarajevo's Lion Cemetery since the surrounding buildings gave more cover against sniper fire. After the funeral ceremony, the coffins were buried in darkness.

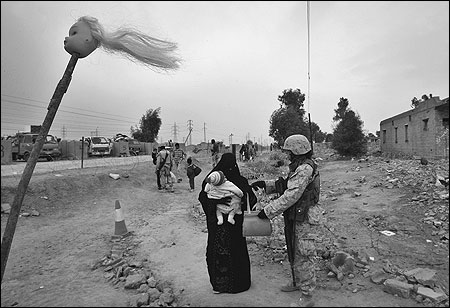

A Palestinian man reads the Qur'an during the last day of Ramadan at the beach outside Gaza City. December 4, 2002.

Gaza is a narrow strip of land that hugs the coast. It's one of the most densely populated areas of the world. The refugee camps are so depressing and sad, but this beach always held something special for me. It's like a refuge from surrounding chaos: quiet, with the bluest of blue water, and soft sand. Often I would go there in the morning to watch the young men fish as they balanced on boats not much bigger than surfboards, casting their nets deftly into the sea. This seemed one of the few signs of normal life in Gaza. It was on the last day of Ramadan that I saw this man saying his midday prayers; he sat a little further up the beach where no one else was near.

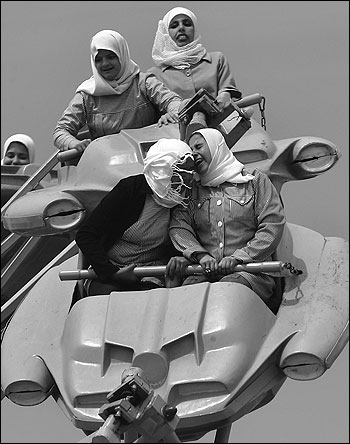

Palestinian girls enjoy a ride in an amusement park outside Gaza City. March 26, 2006.

I'd had a fruitless and boring morning at the Rafah border-crossing waiting for a fifth day to see whether it would open. It did not. On my way back to Gaza City, I saw a group of schoolgirls enjoying a ride at an amusement park. The machinery looked old and rusty, but they didn't care. And when this ride was over, they ran from ride to ride, laughing and giggling with one another.

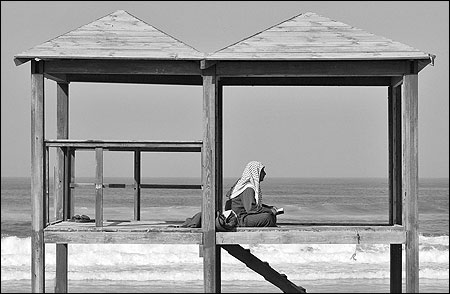

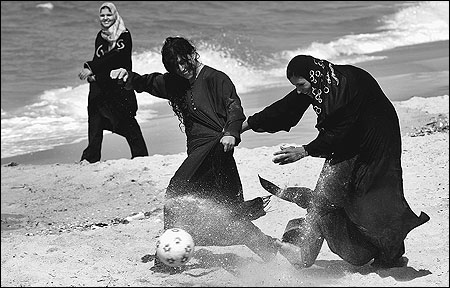

Palestinian women kick a ball at the beach in Rafah, in the southern Gaza Strip. March 22, 2006.

I was traveling down the newly opened coast road near Rafah when I saw women and girls playing joyfully on the sand, something I'd never seen happen before. Palestinians had not been able to use the beach because it was beyond the Gush Katif settlement. But in the summer of 2005 the 8,000 Israeli settlers had to leave as part of the disengagement plan, and Palestinians were able to visit this beach again. After watching these young women enjoying a peaceful early evening, I jumped out of my car and right away a soccer ball came in my direction. I kicked it back, and we played for a few moments before I started to take some pictures. It was such a beautiful evening, and I stayed nearly an hour, chatting with the girls. They were so thrilled to test their English, which they had learned in school, and when I told them that I was from Germany they were eager to learn some German words.

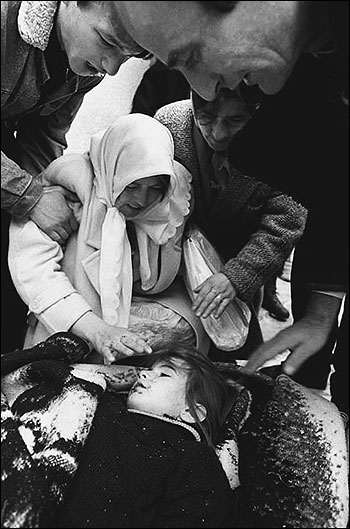

Family members arrive to attend to Emina, a six-year-old Muslim girl, who died after a shell landed near her in Sarajevo. January 11, 1993.

I only learned her name, Emina, and age, six, after she died. I first spotted her while I was walking up a hill to get into an area in Sarajevo that had come under heavy attack the night before. She and some of her friends were riding small wooden sleds down the hill, enjoying a quiet, sunny but cold winter morning. I passed the girls and was touched by how children can cope with war, how they can forget it for a few moments and pretend life is normal as they run and sled and play. When I was on top of the hill, a shell landed where the children were playing in the snow, and I ran down to see what happened. There was Emina lying next to her sled; shrapnel had hit her on the neck and cut the main artery. At this moment, she still looked alive.