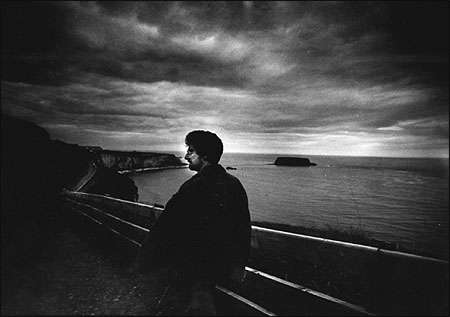

“People in Northern Ireland are frightened and fearful their identity is going to be lost,” says Martin O’Brien of the Committee on the Administration of Justice. In a land where justice is often one-sided, O’Brien works for all sides. Photo by Stan Grossfeld, courtesy of The Boston Globe.

For the past five years, I’ve had the rare privilege and burden of being the only staff American news reporter in Northern Ireland. When the unexpected strikes the peace process here—cease-fire breakdowns, late night riots, surprise political shifts—The Associated Press occupies the inside track compared with other U.S. media outlets. That’s partly because of the network of local sources I built up before the peace process began. Just as often, it is because few other U.S. reporters have ever paid much attention to the undercurrents of backwater Belfast, so by the time the story hits the rapids, my competition is often still trying to get through Heathrow.

Back in 1990, when I landed here to do a master’s degree in Irish history and politics and to cut my teeth as a foreign correspondent, most of my friends thought I was making a foolish decision. The place was mired in a medieval holy war that had little, if any, relevance to the outside world: That was the conventional wisdom. But my student wanderings through Northern Ireland during the late 1980’s had already convinced me that this wasn’t right, and that U.S. newspapers’ spotty coverage of life here rarely rose above confused caricature, and the spot story itself was primed to take off.

Even so, I’d wrongly presumed that the AP had well-established correspondents—bureaus, even!—in Belfast and Dublin. I only accidentally discovered this wasn’t the case while I was completing my master’s thesis and starting to carve a niche as a Belfast-based freelance writer. The first two newslean winters meant a struggle to keep the project alive. I drove a junkyard car, complete with a Flintstones-style hole in the floor; typed with gloves on rather than waste money on coal for the fire, which I was never very good at lighting anyway, and tapped my credit cards to the max in hope that things would come right.

Thankfully, the bureau chief and news editor at AP London gave me increasingly regular assignments to test what I could deliver. Success begot success and I gradually wrote my way out of debt. Soon I was working full time for the AP, initially in London. After doing tours in Rwanda and Croatia, in 1995 I became the agency’s first-ever Ireland correspondent, filing stories daily on events in both Northern Ireland and the Irish Republic.

These days, I have an office in my Belfast home that looks like the Ulster wing of the Library of Congress, with files and books from floor to ceiling. And thanks to mobile phone modem cards for my laptop, when the story moves outside Belfast I can file copy to the appropriate editing desks in London and New York just as fast. When summertime street confrontations over Protestant marches spark rioting in Northern Ireland, my newspaper competitors go to bed at their Belfast hotels. Meanwhile, I am camping in my car, filing leads on the latest casualties and destruction, driving warily through broken glass and past menacing youths and fretting about keeping my batteries charged through the “cigie” lighter. This redeye work usually appears only as insert material under other people’s bylines in the reputedly most authoritative newspapers; the rest of America’s press, more honestly, just runs the AP story directly.

At times my job of covering both parts of Ireland, simultaneously and round the clock, has seemed like asking a one-person bureau to report concurrently on Israel and Egypt. Though Irish nationalists may want the whole island to be united under one government, the contemporary reality is of two quite different worlds. There is the north with its headline-grabbing spasms of violence, set against a backdrop of rival British Protestant and Irish Catholic demands. And there is the south with its less reported development into one of the most economically dynamic, outward looking, and culturally stimulating nations of Europe.

For a wire service supplying subscribers in Europe as well as the United States, there’s no such thing as a day when Ireland doesn’t produce at least one story. I’ve probably made the 100-mile drive between Belfast and Dublin a few hundred times, sometimes earning bylines from both datelines in the same news cycle.

The peace process that began in Northern Ireland in 1993 has dominated my life, with 1998 the most exhausting year. A gun attack on a Catholic pub at midnight on New Year’s Eve of that year turned out to be a signal of what was ahead. As the champagne went flat at our Belfast home, my four-months- pregnant wife and I toasted in the New Year behind police scene-of-crime tape, talking with stunned survivors and watching forensics officers picking spent bullet cartridges off the pavement.

Events grew in intensity with each week.

- A spree of revenge killings.

- Round-the-clock negotiations that produced the Good Friday peace accord.

- An island-wide referendum to confirm sufficient public support for the deal.

- A far more problematic election to form a provincial legislature from which the new Catholic-Protestant administration was supposed to be drawn.

- A week of rioting that ended after three young Catholic boys were burned to death in their Protestant neighborhood.

- A car bomb planted by IRA dissidents that killed 29 people, the bloodiest attack in three decades of conflict.

Somehow in the midst of all this, I followed the Tour de France around the south of Ireland, the Pogatchniks shifted to a new office-home, and Jan gave birth to our first child, David.

Too much of the time, the sheer demand to produce copy as quickly as possible means reporting is done from the desk and over the phone. This was particularly true during the run-up to the Good Friday accord when, working alone, I often could beat the hundreds of reporters encamped idly outside the negotiating venue by phoning the politicians inside, directly on their mobiles, before they held their set-piece press conferences on live TV.

When a story is developing in Belfast, the deadlines keep coming and the phone keeps waking the baby. I rise to the seven a.m. radio news and soon am typing up the day’s first lead, bound for morning newspaper deadlines in Europe and afternoon deadlines in America. I try to get my breakfast by lunchtime, because by then it’s time to prepare a story for the U.S. morning papers. On those occasions when Belfast is locked in late night riots or negotiations, this story must be led and revised past midnight, when it becomes time to produce a fresh story for a new world-members cycle bound principally for Asia. On and on this cycle continues, complicated by an editing process that stretches across the Atlantic to Manhattan. Requests come in, too, from AP Radio in Washington to explain the latest news: “So, Shawn, understand there’s been some trouble in Ireland. You have a minute?”

At times I’ve looked with envy at my wire service competitors in Reuters, who usually have two to five reporters in Ireland covering the same beat and for better pay. They take turns and get to sleep more regularly than I do. But the fact that I had primary responsibility for producing the Belfast copy worked to AP’s advantage. While I could remain focused on producing a single story, wrapping together breaking political and paramilitary events, members of the Reuters team were often filing competing stories that their news desk either had to spend time combining or, more often, simply passed along in a non-publishable fashion to subscribers.

It would have been impossible for me to build a deep-seated list of sources under the pressure of recent times. Fortunately, I’d already built one during my happy wilderness years in Belfast starting in 1991, when I socialized freely in Belfast, camping out on people’s living room sofas after hours of increasingly candid talk and a few too many shots of Bushmills. These days spent with people from all walks of life—industrialists, politicians, soldiers, cops, paramilitary outlaws, ordinary decent criminals—provided me a network of intimate acquaintances that, though not bulletproof (five good sources have been killed, two others died accidentally), proved priceless once the bud of Northern Ireland’s peace process unexpectedly appeared seven years ago.

As a result, I’ve not been reliant on the official channels of information within the British and Irish governments, police and party press officers, who are often deliberately kept as the last to know anything. Instead, I can make well placed calls to quickly stand up or knock down almost any story, then follow up with official ports of call if necessary. At one practical level, this has allowed me to confirm details of a bomb blast or a killing hours before they’re officially released, essential in developing angles for the story.

Whereas the AP’s spot coverage on Northern Ireland was once marked by by-the-numbers naiveté—“Police wouldn’t say if the victim was Catholic or Protestant” and “No group claimed responsibility for the shooting/bombing” were favorite newsy-sounding admissions of failure—confidence in my sources allowed me often to scoop the competition. For instance, just after midnight on February 1, I was first to confirm publication of an arms decommissioning report that, because of its negative findings, would bring down Northern Ireland’s new power-sharing government. Competition on confirming this development was severe. Yet the official sources continued to deny its publication for several crucial hours. During this time, U.S. papers were going to print and Reuters kept leading with official denials as its Irish-based reporters didn’t find independent confirmation of the report’s existence.

The U.S. competition is usually farther behind, or absent entirely. After one particularly traumatic overnight clash involving cops and Catholics in 1997, I’d already been knocked out by a brick, revived and filed three leads by the time The New York Times arrived on scene—and, to my professional disgust, began interviewing me about what had happened, notepad in hand.

Some of the London-based correspondents acknowledge my edge and willingness to help with sources by making occasional “So what-cha think’s gonna happen?” calls. The subtext is always: “Do I need to book a flight, or can I stay in London?” Others offer the full-court squeeze over dinner, by the end of which I can feel less like a reporter and more like a source. But as the Northern Ireland story has turned increasingly less violent and more political, the London-based crew have actually hired local journalists to provide them more formal advice on the significance of events.

More and more often these correspondents are producing Northern Ireland stories under London datelines. Sometimes the dateline gap stretches credulity further. During one important juncture in the process last November, when I was interviewing George Mitchell about his unexpected success in brokering a deal between Sinn Fein and the Ulster Unionists, The Washington Post covered the story under datelines of Madrid and Cincinnati! And no, there are no picturesque Irish villages bearing those names.

Building this competitive advantage for the AP has felt rewarding. Yet, as I begin a sabbatical year to write a book about the past decade’s dramatic changes in Northern Ireland, I am also mindful that the crush of breaking events means that many of the more touching, meaningful stories have gone untold. Conversely, most of the 2,000 or so articles I’ve produced have been too superficial and incomplete to have the impact I would have liked. The reason: To report honestly from Belfast for an international audience means winning a high-pressure struggle to reconcile two competing demands. I must present the day’s news in such clear and simple terms that it cannot possibly confuse anyone. But at the same time, I must do this with sufficient context so that readers can form a realistic, fair picture of the environment in which news is taking place.

In practice, within the confines of a 500-word breaking story, these two objectives are often hopelessly at odds. The demand for clarity serves to obliterate any hint of sophisticated presentation. Gray, complex realities become a black-and-white media confection suitable for the least demanding palates.

Every person and thing in the Northern Ireland story must be explained, but there’s no room to explain any of them adequately. So most are regularly chopped out of the portrait entirely. The rest are labeled in a cursory manner—for instance, the IRA-linked Sinn Fein party; the Ulster Unionists, the province’s major British Protestant party; Peter Mandelson, Britain’s minister responsible for Northern Ireland, et cetera. Even this exercise can quickly consume a third of an AP story’s allotted space.

This shorthand labeling can cause all kinds of interpretive problems. Take the most basic one in Northern Ireland, “Catholic” and “Protestant.” It’s been impossible for me to get away from portraying this society as one torn between two religious tribes, because that was the convention established long before my arrival. Reflecting this presumption, editors unfamiliar with the story regularly attempt to characterize the entire toll of the past three decades’ conflict, more than 3,600 dead, as victims of “sectarian violence,” a.k.a. the product of Catholic-Protestant hatred.

Yet the religious labels mislead. At least half of the killings had no clear sectarian motivation behind them. Irish Republican Army activists, only some of whom are practicing Catholics, didn’t seek the denomination of the more than 1,000 soldiers and police they slew. With few exceptions, the killers from all sides weren’t motivated by their take on Christianity—which is the only conclusion a general audience could possibly take from copy that labels protagonists as Protestants and Catholics.

The reality is that, just as with Catholic Croats and Orthodox Serbs in the former Yugoslavia, the conflict in Northern Ireland has been driven by competing nationalists, British and Irish, whose antagonism has been reinforced by many factors, only one of which is religious division. Whereas members of the international media acknowledged the right of Croats and Serbs to hold their national identities and rarely referred to their different religious foundations (I’m not forgetting the Muslims, but that is a different article), most visitors to Northern Ireland from President Clinton on down make the mistake of referring to everybody here as “Irish.” This misconstrues the whole dynamic of the conflict. Not everybody in the Ulster Unionist Party is Protestant, for instance, but they all would consider themselves British. The best compromise I’ve been able to inject into AP copy has been to refer to the province’s “British Protestants and Irish Catholics,” but I doubt this has really changed readers’ perceptions of the place much.

I’m determined to keep on trying. For a long time I just thought of Ireland as my assignment—and it is an incredible assignment. But it’s also become my home, better known to me than my native Washington state. Just as I’ve found it hard to switch off from daily events while working on my book, I can’t imagine ever leaving the place. Not while there are still so many good stories to do.

Shawn Pogatchnik, the Associated Press correspondent in Ireland, is a 2000-2001 Fellow of the Alicia Patterson Foundation.