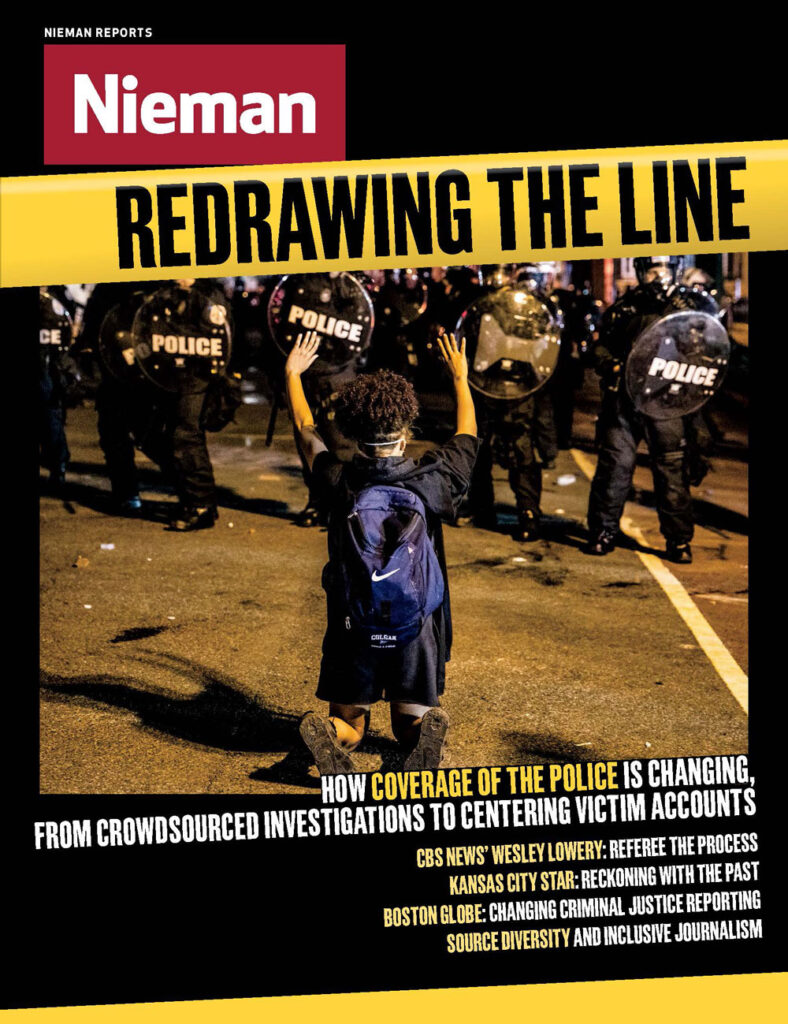

In the wake of the police killing of George Floyd and the increased prominence of the Black Lives Matter movement, editors across the country have made a concerted effort to hire more Black reporters, include more Black authoritative voices, and recount the real life experiences of people of color impacted by systemic racism.

Increasing the diversity of the sources we use and the people we feature is the first and most significant step in creating journalism that paints a more complete picture and is more relevant to audiences. News organizations like NPR and MPR were well ahead of the game. They, along with reporters groups like the Open Notebook and the Database of Diverse Sources, curated by editors of color for experts of all kinds, have been curating open source lists of diverse experts for years. An increasing number of news organizations are following suit.

Since last March, as part of a journalism fellowship from the Donald W. Reynolds Journalism Institute, I’ve been developing a training curriculum on ways to make reporting more reflective of the communities we cover. But when I started, I had no idea how timely — or how challenging — this project would be.

When I proposed my diverse sources project, I believed the biggest obstacle would be getting newsrooms and journalists to accept that this was a worthwhile investment of scarce resources. That turned out to be the easy part, however. Most reputable news organizations understand that being more inclusive is not only the right thing to do, it is also good for business.

But including new and/or different authoritative voices in our reporting, particularly women and people of color, is not as easy as one might think. In fact, my biggest hurdle was convincing them to participate as sources. I was turned down for a variety of reasons. If we are to overcome the barriers to increasing source diversity, we must understand what those barriers are, why they exist, and how we can overcome them.

Recent media analyses have found that there is a trust deficit between Blacks and the media, as well as opportunities for improvement and trust building. An August 2019 Pew Research survey found that 80 percent of Black adults expect that national new stories will be accurate. But a 2020 study from the Center for Media Engagement at UT Austin’s Moody College of Communication revealed they aren’t nearly as trusting about how the media portrays Black communities. This distrust is largely due to the lack of continued engagement.

Reporters who parachute into a community to cover a volatile situation, without any established ties or understanding of that community, are likely to encounter indifference at best and hostility at worst. When people and communities are only news because they are in crisis, this paints an incomplete and/or one-sided portrait.

Christopher Baxter, founding editor of Spotlight PA, a collaborative nonprofit investigative news site covering the Keystone State, says much of the distrust is because journalism historically has failed to provide an accurate and equitable view of certain communities. One of Spotlight PA’s first endeavors was to build a database of diverse expert sources. Of the 400 people invited to be included, about 100 agreed. Baxter sees that as a good start, given the history of state and local media with this population.

“Pennsylvania has not done a good job reflecting communities of color or reporting on the issues that are important to them,” says Baxter. “Thus, we don’t have much of a trust connection or institutional muscle to message to those communities effectively.”

Last summer’s social justice protests prompted a sustained media focus on the ways systemic racism plays out in many sectors of American life, including police brutality, healthcare, employment and education. Researchers who had been studying and writing about these issues for years, with little interest from mainstream media, suddenly found their dance cards full.

Even those who had been denied space or a voice in established institutions and academic publications were suddenly bombarded with requests for media interviews, opportunities to participate in think tank forums, or asked for guidance about what steps to take to correct past wrongs. These entreaties from well-funded organizations and white reporters mostly came without any offer of compensation.

One academic described it this way to me: “We’ve been toiling in this vineyard for decades trying to get somebody to pay attention to social justice and these systemic racism issues, but no one cared. Now that it’s a hot topic, you want to come in, pick my brain, and get the benefit of all my hard work for free. No, thanks.”

ABC News senior producer Jasmine Brown—who is working on crowdsourcing a database of diverse sources, Diversifying Journalism, for a 2021 visiting Nieman fellowship project—has seen this dynamic play out. “In the days after the Floyd incident, you saw a ton of Black academics but there is also burnout,” she says. “When you’re an expert on this issue, and you have been living it and reviewing it every single day of your life, that can be hard. But there’s also a feeling that this is a moment, and you need to capture it.”

Factors like these can make diverse sources reluctant to engage with journalists, as I discovered in an article exploring how the coronavirus impacted kidney disease and transplant procedures. In developing the piece, I realized that, although Blacks are three times as likely to suffer from the disease as whites, my reporting included no authoritative Black voices.

This led me to seek the opinion of a Black female researcher and epidemiologist with extensive experience in this field. The PR gatekeeper was excited about the opportunity but later said the epidemiologist couldn’t meet my deadline. I offered to extend the deadline and reiterated that I only needed about 30 minutes. Her answer was still no.

It took some prodding, but the rep eventually came clean with me: The epidemiologist simply refused to participate because she viewed it as tokenism and objected to being “used.” A couple of months earlier, the rep told me, the epidemiologist’s employer had created a video series designed to recruit more students from underrepresented groups into its bridge program. Only after the video was complete did someone realize that the dozen people featured were all white. They tried to remedy this after the fact by including her at the last minute. She refused to be “tokenized.”

This backstory explained why she believed my interview request was merely performative.

Former Charlotte Observer associate editor Mary Newsom believes experts and academics, especially people of color, are reluctant to share their opinions in the media because they worry about backlash. “It’s a real concern that a public statement by a Black person is going to risk a lot more blowback, and a lot of people just don’t want to be a target,” says Newsom. “There’s enough backstabbing going on in academia that if you’re feeling somewhat vulnerable anyway because you’re a person of color or a woman, you may not want to get anybody’s hackles up.”

The 1619 Project, a historical analysis of the role slavery has played in shaping U.S. institutions, has been adapted into lesson plans in many schools across the country. But some conservatives labeled it “toxic” and “ideologically poisonous,” directing much of their thinly veiled racist and misogynistic vitriol at Nikole Hannah-Jones, the Black reporter who conceived the project and wrote the introductory essay, which won a Pulitzer.

Being willing to open yourself up to ridicule or harassment takes courage, particularly when it concerns a divisive or inflammatory issue. But this kind of invective is not limited to topics that are obviously about race. In the current climate, every subject — even hard science — is politicized. Those who come down on one side or the other are subject to attack and harassment by those who disagree.

Regardless of their CVs, many people of color, especially women, don’t see themselves as qualified to offer an expert opinion or insight. During a panel at the 2019 International Journalism Festival, Amplifying Women’s Authoritative Voice in Media, Laura Zalenko, senior executive editor of Bloomberg Editorial, said that one obstacle to remedying the underrepresentation of women was women themselves.

An internal audit revealed that just 10 percent of outside guests on Bloomberg TV were women and only 2.5 percent of the top news stories cited a woman expert. Those dismal numbers drove the media company to develop a broader initiative to include more women, but the outlet encountered an unexpected problem. “One of the concerns that we were hearing was that some of the women that we were trying to bring on TV said that they weren’t prepared or comfortable doing that,” said Zalenko.

In my experience, Black women are most reluctant to identify as experts because they’ve never been asked and lack the confidence that they can measure up. Last summer, I asked a Black history professor to comment on the state’s decision to revamp the history textbooks long criticized for the ahistorical view of the Confederacy, Civil War, Reconstruction and Jim Crow. In addition to her impeccable academic credentials, the professor had also attended North Carolina public schools and studied those very history books. She declined to be interviewed because she didn’t feel qualified to discuss the history books. She then suggested I speak with two frequently quoted white male academics, the very situation I was trying to avoid.

“It’s unfortunate that we ourselves will point to a person that is of the dominant group because we don’t feel competent, per se. We don’t have many opportunities, and we don’t want to get it wrong when we do get a shot,” says Brown.

Inclusive reporting may not be easy, but it is essential. Here are a few ways journalists can get around the objections of potential sources.

- Redefine who is an expert. In a pre-training survey I conducted to gauge journalists’ attitudes about source diversity, most respondents said they rely on resumes, credentials, and formal training in a particular area to determine who’s an expert. If we broaden our definition of who qualifies as an expert to include lived experience and people who are impacted by the issues, this greatly expands the number and kinds of voices we can include.

- Lay the groundwork first. If possible, try to recruit new sources before you actually need them in a story to avoid making a cold approach when you’re on deadline. “I found that if it’s someone I know tangentially perhaps through a mutual acquaintance, there’s a bit more confidence in the care they’ll receive,” says Brown.

- Explain the process. Whether they are real people sharing their experiences or subject matter experts, few non-media people know what to expect when they agree to be interviewed. Part of our job as journalists is to explain the processes for a print media outlet versus online versus broadcast. Set expectations by letting them know that an hour-long interview might produce one quote, or they might be left out of the story altogether. This way, when the assignment is over, the source doesn’t feel misled and might be willing to be interviewed again.

- Practice cultural competence. The notion of cultural competence is not just for white journalists, says inclusive media consultant Linda Miller, who helped create the Public Insight Network of diverse sources for American Public Media. “Understanding that different communities have different histories and experiences with the press should be the starting point for every journalist,” says Miller. Fortunately, many newsrooms have created training and outreach activities to help the staff develop the awareness, knowledge, and skills necessary to actually listen, engage and build empathy for someone else’s experiences, the central tenet of cultural competence.

Incorporating new and diverse sources in our reporting is well worth the effort, even if they need some convincing.

The Newsrooms We Need Now

As American society—and American newsrooms—grapple with an unprecedented time in the country’s racial justice movement, Nieman Reports is publishing a series of essays about how journalism should respond to the challenges of the moment, from accelerating journalists of color moving into senior decision-making roles to improving coverage of racism and white supremacy.