Commemorative Double Issue

What you [see] here is a collection which reflects the substance of the first 53 years of the conversation journalists have engaged in about their rights and responsibilities in the pages of Nieman Reports. At times you will find an article that opened a new argument or ended an old one. Throughout you will hear the voices of journalists committed to their work challenging colleagues to raise the standards of discovering, reporting, writing and editing the news in a context meaningful for navigation within a free society. – Bill Kovach

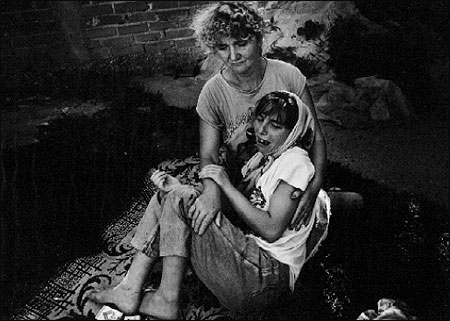

Widow of Muslim man killed in Banja Luka is comforted. Photo courtesy of Michele McDonald.

[This article originally appeared in the Summer 1998 issue of Nieman Reports.]

These photos were taken in August, 1993 in Serbia, Bosnia and Kosovo for The Boston Globe. Reporter Sally Jacobs and I were sent from Boston to do stories that would give Globe readers more perspective and understanding of the chaos in the former Yugoslavia than they could get from the daily reporting of the war.

The photos each tell a specific story, but together I think they give a more powerful glimpse into a terrible time in Balkan history.

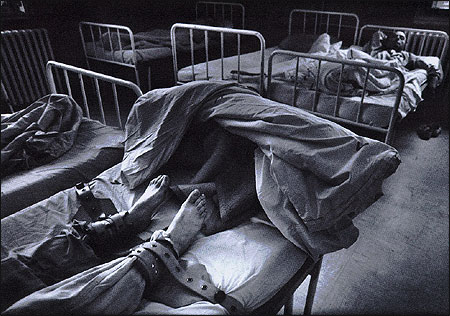

In Belgrade, I photographed a man strapped to a bed in a mental hospital. There were soldiers there who had literally gone crazy fighting the war. The Serbs allowed me access because they wished to show how the world’s sanctions were hurting them. There were no psychotropic drugs left—so they were forced to strap down violent patients. The nurse, who pulled back the sheet to show me this man’s legs, cried.

The story is not so simple, though. The economic sanctions allowed food and medicine into Serbia—but the government had to buy them. The Serb government had money to support the war effort but chose not to buy desperately needed medications.

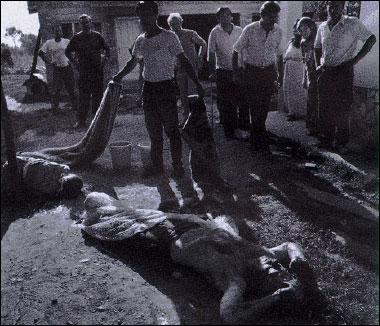

The very first morning we were in Bosnia, we heard of a massacre during the night in a small Muslim village 30 kilometers from where we were staying in Banja Luka. We were in Banja Luka, a stronghold of radical Serbs, to report on what life was like for the region’s remaining Muslims. Although the Serbs, who controlled the roads, told us the village was closed, we drove there and were able to enter because the roadblock was unattended. (It turned out the Serbs were at a meeting with U.N. workers who had also heard of the killings.) The heat and humidity were searing but people in the village had not yet buried the five people, including two elderly women, who were tortured and killed. They were afraid the Serbs would deny anything had happened. I took the photos of the villagers showing us the dead and the mourning widow of one of the killed men here. Sally wrote the story of the year of terror and “ethnic cleansing” of one small village.

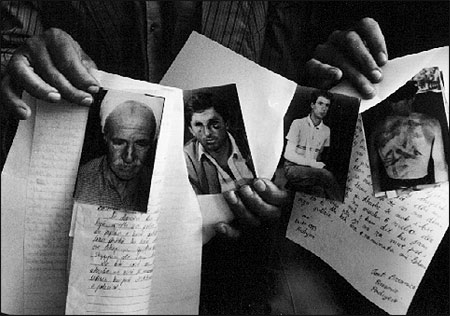

Finally, we visited Kosovo, recently catapulted into 1998 headlines because of the violence erupting there. International human rights monitors had just left Kosovo when we visited in 1993, and the Albanians were attempting to continue to document human rights abuses by the Serbs. Afraid to show their faces, the Albanians showed us photographs and written reports of beatings, etc., of Albanians by the Serbs. The Albanians had established an alternative society with their own President, government, clinics and schools. I photographed the smoking boy when I was out walking in the middle of the day. The Albanians had stopped sending their children to school when the Serbs refused to allow the students to be taught in the Albanian language.

Albanians show reports of beatings by Serbs in Kosovo.

Albanian boy no longer goes to school.

Bodies of the victims of a massacre in Liskovac.

Serbian soldiers in mental hospital in Belgrade.

Photos courtesy of Michele McDonald, a 1988 Nieman Fellow. She is a freelance photojournalist.