Commemorative Double Issue

What you [see] here is a collection which reflects the substance of the first 53 years of the conversation journalists have engaged in about their rights and responsibilities in the pages of Nieman Reports. At times you will find an article that opened a new argument or ended an old one. Throughout you will hear the voices of journalists committed to their work challenging colleagues to raise the standards of discovering, reporting, writing and editing the news in a context meaningful for navigation within a free society. – Bill Kovach

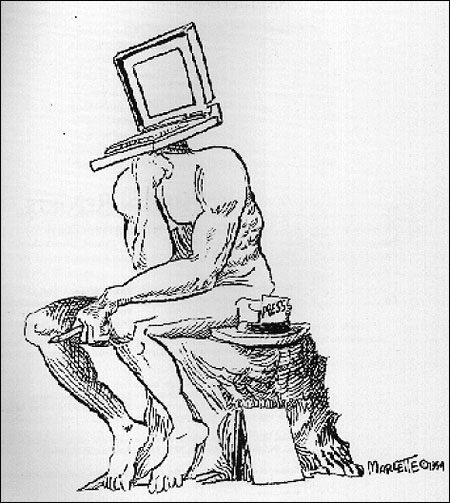

Cartoon courtesy of Doug Marlette.

[This article originally appeared in the Spring 1994 issue of Nieman Reports.]

How can a news company survive and prosper, given the current communications free-for-all? What’s the right choice? Anybody who claims to know for sure is either a fool or a salesman. To judge from the announcements of new divisions, mergers and experiments, every company involved in journalism is suddenly searching for the answer.

Unfortunately, it may not be the right question.

Certainly the convergence of technological and market forces in the late 20th Century has created a historic turning point for journalism in this country. But newspaper publishers, editors, reporters and broadcasters tend to frame the problem solely in the most narrow economic terms—how can my company grab a piece of the action?

Early in this century, newspaper journalists dominated the flow of information in their communities. News, raw data, advertising messages, communication to and among the citizens—newspapers were in the business of publishing them all, and the distinctions were not particularly important. They were all part of the same manufactured product. A journalist, meanwhile, was a person who had access to an audience through this one-way mass distribution system.

This world has virtually disappeared, of course, as control has passed to audiences and advertisers. Local journalists no longer monopolize the megaphone. New competitors proliferate, exploding the old newspaper business into many parts. News has become a commodity, available from CNN 24 hours a day. Computer-based on-line systems deliver raw data on demand. Television, radio, print niche competitors and the Post Office have segmented the advertising market. Citizens can talk back on radio call-in shows and online systems—when the plentiful entertainment and leisure options don’t drown out all public discourse. In the age of “America’s Funniest Home Videos” (not to mention the video that eventually caused Los Angeles to erupt), just who is a journalist and who is a publisher is up for grabs.

We’ve hardly begun to adapt to these changes. Now comes the interactive, multimedia world—in some as-yet-to-be-determined form. When newspaper publishers haven’t been tossing and turning in the night, they’ve been busy exploring personal communications, entertainment and transactional services—the products expected to drive change in the new communications environment. Or they’re taking old forms and formats and retrofitting them for use on line, trying to adapt the strengths of an old medium to a new medium no one yet understands. As anyone who has studied the media will tell you, that won’t be enough.

But what will be enough? Nothing less than re-imagining what it means to be a journalist in a democratic society, with these new tools at our disposal. Journalism companies won’t have a future (at least as journalism companies) unless journalism itself has a future. Who, what, when, where, why and how are the urgent ethical and practical questions we need to ask about journalism itself.

Given the new technological and economic realities, when will journalists get in the way of democracy, and when will we be essential to it? What are the new opportunities for journalists to connect with citizens and citizens with their governments? Who is a journalist and what is journalism, in a world where data, information and raw video will be plentiful and where everyone with access to a computer and a telephone will own their own press? What will make professional journalism valuable?

These are the sorts of fundamental questions anyone concerned about journalism’s survival needs to ask. The industries driving the changes in the new communications systems—telephone and cable TV companies, computer and entertainment companies—aren’t going to ask these questions, let alone answer them. The business sides of newspaper and broadcasting companies may not ask them, because they don’t obviously relate to the short-term bottom line. Indeed, the business people—for all the hype surrounding their decisions—are often as clueless as the rest of us. I sometimes wonder whether the frenzy of media mergers has been fueled by the search for a partner who understands what the hell is going on.

Journalists, therefore, have got to get a whole lot more sophisticated about understanding what’s going on and what it means—to journalism, to the political system, to the public, and to the old and new businesses that sell journalism under the protection of the First Amendment. Then we’ve got to ask ourselves what we need to accept and what we need to do, before it’s too late.

Here are some ideas about where to start, individually and collectively.

1. Launch a massive technological literacy campaign for journalists.

We’re making progress here. Many individual journalists are teaching themselves, and organizations such as Investigative Reporters and Editors are providing better and better training opportunities. Recent Pulitzer Prizes have showcased the difference computer-assisted reporting can make.

Still, given that personal computers have already been around for more than a decade, it’s shameful how slowly we’re still moving to take advantage of the new tools for reporting, thinking, communicating and telling stories. The nation’s newsrooms are full of reporters and editors who have no idea how to mine the vast resources of the online world—much less how to prepare themselves to produce journalism for interactive, multimedia formats. It’s as though a whole generation of journalists and journalism educators secretly believe that they’ll be able to retire before having to relearn their jobs.

For their part, many publishers talk a good game about the central importance of the information franchise, arguing that substance and content—not delivery systems—will drive the future. That’s good news for journalists. Yet the big investments go into new delivery systems and mergers, rather than into the hiring, training and equipping of the people who gather information.

We can do better, much better. And we must, before our ignorance kills us. The communications marketplace is already full of information providers who spotted the new opportunities traditional journalism companies have missed. Nexis and CNN spring immediately to mind.

People at the top of the profession, in a position to negotiate for resources, need to provide more aggressive leadership, inspiring their colleagues and their companies to adapt old values to new realities. Reporters and editors need to be given time and the equipment to learn new skills and imagine how to do their jobs better. Newsrooms need to be energized by the possibilities, not immobilized by fear.

Proposed innovations need to be funded and rewarded as experiments that will increase the learning curve.

We also need to insist that the journalism schools train their students for the future, not the past. Nobody should graduate from a journalism school now without sophisticated computer skills, a broad introduction to working in various media, and the understanding that their jobs may require them to work well in teams.

Journalists in the future will be asked to perform new functions, in new jobs, in new market niches. Will we be ready?

2. Educate ourselves about the ethical, economic and political issues surrounding the “information highway”—and cover them aggressively.

The hype about any new technology always races ahead of serious questions about the moral and social implications. Certainly that has been the case so far about the multimedia, interactive future, which has been covered in the mainstream press as a business story, a feature story, and a subject for grumpy Luddite columnists. This failure is due, in part, to the ignorance just discussed, not only of technology but of history as well. Important technology stories are waiting to be discovered in the schools, museums, libraries, hospitals and governments. But too many reporters and their editors don’t know where to look or what questions to ask.

The restructuring of the communications system is an enormous story. So far, the agenda has been shaped by the big industries most affected, especially telephones and cable television. The nation’s press could do a big service by helping frame the debate in broader terms—not as a business story, but as a public policy story that will affect every citizen for decades to come. If access to the information highway will mean access to the democratic system, as many experts believe, what protections need to be built-in to make sure that no one is left out, that not just the elite benefit?

Educating ourselves about these changes will have an important side effect: a deeper understanding of the stakes for journalism. If huge, new companies are allowed to control both the conduits and the content that moves through them, what are the dangers? If the system develops as pay-per-view, what are the implications for news programming?

These are urgent questions in a year when major communications reform bills are moving through Congress.

3. Make the case that journalism is worth saving—then sell it to the public.

Technology and economics aren’t the only challenges we face. Indeed, one might argue they aren’t even the greatest ones. Our own performance has led to a deepening credibility problem, which in turn feeds the desire some people have to bypass mainstream journalism and search for other information sources.

We’re arrogant, we’re ignorant, we’re destructive. If citizens are disengaged from politics, our cynicism is partly to blame. This litany from critics inside and outside the profession is familiar—and mostly ignored in the nation’s newsrooms.

It’s not just that journalists failed to report well on such major stories as the S&L crisis and the massive redistribution of wealth that took place during the 1980’s. The problem extends deeply into the journalistic norms that favor drama, conflict, celebrity and toughness when it comes to defining news.

“The blunt truth is that tinkering and half-measures will no longer do the trick,” Washington Post media writer Howard Kurtz said in his book “Media Circus.” “There is a cancer eating away at the newspaper business—the cancer of boredom, superficiality, and irrelevance—and radical surgery is needed.”

Novelist Michael Crichton went further in his speech last year to the National Press Club, labeling us dinosaurs whose ingrained habits for gathering and reporting the news are little more than “a way to conceal institutional incompetence.” Our product, he said, is “flashy but it’s basically junk. So people have begun to stop buying it.”

People also don’t understand why good journalism matters. Public support for government censorship during the Gulf War dramatically illustrated how few citizens understand the difference between propaganda and independent reporting, and therefore the need for a skilled, free press. The popularity of tabloid TV shows deepens the problem, especially when mainstream reporters start behaving like infotainers, promoting every Tonya Harding story into a major international event.

In short, we do not really know how many publics there are. If that is true now, imagine the problems journalism will face in the new world. Who will be our publics? How many are there? What information will they want? In what form? How will they want to get information? When and how often will they want the information? How can we serve such a fragmented market? We cannot decide what we will do until we understand the needs and desires of the segments that make up the market.

If professional journalism is to survive, professional journalists have to be willing to be as tough on ourselves as we routinely are on others. And we need to understand that there’s nothing sacred about how we’ve defined our jobs in the past—which is where the new technologies and economics may provide us with an opportunity.

It is easy to imagine a future in which the newspaper won’t be dropped on the front porch. The “newspaper” can become the community’s front porch. New technologies will make it possible for people to gather, to gossip, to debate, to play a game together, because the “newspaper” has made it possible for them to find each other. Journalists will sit on the porch, too, telling their stories and listening to people’s reactions. Just behind the front porch, through the front door, will lie the world of information and ideas and people. The “newspaper” will help anyone who walks through in search of a fact or a service, whether they’re looking for the most minute detail about the local sandlot league or about desert sands half a planet away.

In this future, journalists can more often be perceived as raconteurs and bridge builders and researchers, not just cynical public prosecutors. Indeed, electronic mail and “real time” forums are already making new relationships with audiences possible.

So we can and should make the case that journalism is worth saving by improving our performance and reaching out to readers and viewers. But we should consider finding other ways of reaching out as well.

We might call for a new Hutchins Commission report for the 21st Century—a blue-ribbon panel of respected Americans who can study the purposes and performance of the press. This group may be precisely the place to sort out the whos, whats, whens, wheres, hows and whys of responsible 21st Century journalism. The commission could, for instance, study the democratic functions of town hall meetings, talk shows, electronic interest groups, and investigative reporting. Facing the future may well mean coming to terms with when journalists aren’t needed, as well as when we are.

Or, as Bill Kovach, the Nieman Foundation Curator, has suggested, journalists might get involved in popular culture, creating scripts and series that tell the story of real journalists doing their jobs.

Whatever the strategy, we’ve got to find some high-profile ways to argue that raw data and video, uploaded and downloaded in every home, can’t substitute entirely for professional journalism in a free society.

4. Advocate for, support and pay attention to serious intellectual work that could have an impact on public interest journalism, including the boldest experiments, no matter who is funding them.

If our job is to help educate the public, we do it, too often, blind. How do ideas spread? Why do some stories have impact and others die? How do people learn from media? What do they retain and what do they forget? What’s the role of fun, and aesthetics, and the ability to talk back? What kinds of stories are best told in print, which in video?

We can’t afford to guess about questions like these. Serious corporate thinking is going on about interactive video advertising messages, sophisticated new computer games, new computer agents to do our information retrieval for us, and lord knows what else. A few journalistic pioneers are out there experimenting with and promoting new ways of getting citizens involved in community dialogues. But we need more high-profile and intellectually rigorous efforts to look at the kind of communication a democracy needs—and how indeed it might need to be marketed.

Listen to this description of the kind of research going on at Xerox’s research facility in California: The head of the facility “envisions a new, dynamic ecology of communications—rather than a static architecture of information.”

That’s just the sort of sophistication we need about news and communication in a political system. We may get some of it from MIT’s Media Lab, where investigators are exploring the possibility that news could become a service integrated into your life, rather than a product you retrieve.

So far, the high-profile redefinitions of journalism—The Orange County Register and Boca Raton News, for instance—have advocated viewing readers as customers who need to be given what they want. That’s an important antidote to top-down highmindedness. But it may not go far enough. Maybe, as Tufts’ political scientist Russell Neuman has suggested, we need to start over and ask, what is journalism that serves the people—and how can we fund it?

Since that sort of big project is unlikely to be supported coherently by an industry that has always lacked serious R&D, independent researchers and journalists will probably have to assemble the pieces on their own, by studying bulletin board systems, 24-hour local cable news channels, the computer industry’s R&D, the first interactive television experiments, and much more. We need to be open to learning from innovators, whenever and wherever we find them, inside or outside journalism, inside or outside Big Media-funded projects.

Will the bulletin board systems really make newsrooms more accountable? What kinds of public dialogues work best on line? When is it a good idea for reporters to carry video cams, as we carry tape recorders now, and when is it really a bad idea? What can we learn from the newspapers-on-TV experiments in Chicago and Philadelphia? Will Xerox show how new communication systems can change human relationships? Will the alternative press and specialized magazines show the way, as they so often have during the last 30 years? Should freenets be absorbed by local news on-line systems, or should certain kinds of public information be protected from proprietary commercial interests?

These are the sorts of questions we need to study, while remaining open to the surprising answers we may find. Certainly the early newspaper-funded video text experiments hinted that personal communication, rather than data retrieval, is central to the new on-line cultures. That’s a message that might have set newspapers on a different course much earlier—if they had heeded it.

In short, we need to unlock our imaginations, deepen our knowledge, learn to see the intellectual box we’re sitting in. We need to get beyond what University of North Carolina Professor Donald Shaw has called “analog thinking in a digital world.”

5. Consider whether we need a new advocacy organization for journalists.

Do any of the existing organizations have the muscle and the vision to redefine journalism? Maybe. Or do we need to make a fresh beginning, as the newspaper publishers recently did? New York University Professor Jay Rosen has suggested a Union of Democratic Journalists, dedicated to re-imagining the purposes of the profession.

Journalists, I believe, need to carefully differentiate the stakes we must defend from the stakes of our employers—or even the fate of the particular medium we have preferred to work in so far. The corporate identities and product lines of our employers will change. The media are all going to blend together.

We need to understand that what we have in common is far more important than what separates us, whether we practice our journalism as mainstream reporters, book writers, independent documentary filmmakers, magazine editors, public radio correspondents, television magazine producers, or alternative press columnists. Powerful forces are arrayed in opposition to the quality journalism and dissenting voices a democracy needs.

So we don’t need an agenda for newspapers, or television, or radio—how to save them, how to improve them. We need a new agenda for journalism and perhaps an organization to help us move beyond our lone hero culture.

Such an organization could advocate for the ideas already mentioned on this agenda. It could certainly facilitate communication about innovation. And it could help explore new ways to finance public interest journalism.

The current regulatory fight over the shape of the new communications system is a good place to start. Journalists need to consider joining with librarians, public educators, and public interest groups in lobbying over access and pricing issues. Along with these groups, we have an interest in keeping public information free or cheap, and access open to small competitors, such as journalists who may want to open their own shops. Our employers may well have an understandable interest in protecting their investments by limiting access and charging high prices for easy access to large databases.

Then there are the coming battles over intellectual property. Again, journalists may need to part ways with our employers. We will have an interest in preserving the most open intellectual marketplace possible, where those who generate knowledge can make sure potential readers get access to it and authors get compensated fairly for repeated on-line uses.

In other words, journalists have to find new ways to work together because the huge once-in-a-lifetime story we need to react to, to mobilize our resources for, is journalism itself.

So there you have it—an attempt to address some of the opportunities and threats before us. We need to help each other learn and act. After all, when it comes to facing this complex future, there’s really only one ethical stance for committed journalists: tough-minded hope.

Katherine Fulton, Founding Editor of the North Carolina Independent and a 1993 Nieman Fellow, is teaching courses on media technology and women and leadership at Duke University’s Sanford Institute of Public Policy. She would like to thank current and former Nieman Fellows Melanie Sill, Katherine King, Francis Pisani and Phil Meyer for their contributions to this piece.