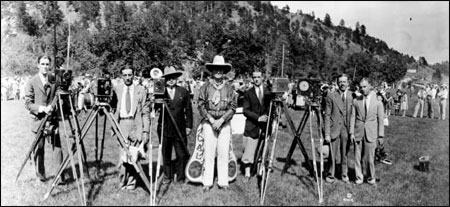

President Calvin Coolidge in cowboy outfit with press photographers. Photo courtesy of the Library of Congress.

[This article originally appeared in the September 1964 issue of Nieman Reports.] The press conference as an organized biweekly meeting was instituted by Woodrow Wilson, fell into disrepair under Harding, and was reinstituted in a very limited form by Mr. Coolidge. Press relations of earlier Presidents had been individual, informal, unconstitutional, down through Theodore Roosevelt and Taft. Mr. Wilson, with his concern for open covenants, wanted to maintain a public dialogue through the press. But the World War closed in on him and cut it off, not before he was glad to be rid of it.

Warren Harding’s flamboyant vocabulary of "normalcy" did not lend itself to clear channels of communication, and he seldom bothered to be informed. So Secretary of State Hughes had at times to take a hand to straighten things out the day after a press conference. After one gaffe that stirred international complications, Harding restricted the conference to written questions submitted in advance. Harding’s skin, also, was too thin to take press criticism; when scandal mounted in the unhappy later part of his administration, he let the press conference wither away.

Mr. Coolidge further restricted the limited form that Harding tolerated. The President could not be quoted. There would be no oral questions, nothing spontaneous. Correspondents would submit written questions in advance and use such replies as the President vouchsafed, only as background information. "There ought not to be any reference to the fact that there is a news conference here," he admonished the correspondents.

On the authority of Lyle Wilson of the United Press, who was there through the whole period, the editors say Mr. Coolidge approached these conferences relaxed, with no preparation. When he picked up the little pile of questions he was seeing them for the first time. Incredible as this seems, internal evidence bears it out. Often enough his answer was that he had no information on the subject, and this was announced without the slightest intimation that he meant to find out. None of this: "We’ll have that for you next time, make a note of it, Pierre." No, the President was making himself available to the reporters, insofar as convenient, to satisfy their curiosity about such matters as had fallen to his attention.

It was always a matter of intense curiosity what was on the little slips he let flutter down on the desk as he shuffled through to find one he chose to answer.

"I haven’t any information about the action of the Federal Reserve Board in lowering the re-discount rate," or "We have got so many regulatory laws already that I feel we would be just as well off if we didn’t have any more."

The slips had already had a cautious screening by his secretary, C. Bascomb Slemp, who was the kind of Republican who could survive as a congressman from Virginia. His relations with the press were built on mutual suspicion. Slemp went on to be Chairman of the Republican National Committee.

It never happened when I was there, but Lyle Wilson says that on occasion Mr. Coolidge would go through the whole pile of questions and find none to his liking, then blandly announce, "I have no questions today," and the press corps would troop out, newsless.

This was a different era. Correspondents were a different breed. Mr. Coolidge refers frequently to his desire to be helpful to the press. He wants to give them all the information he can. He always talks as though this was a personal favor he was doing them.

"I haven’t seen the Muscle Shoals Bill and know little about it. There is nothing I can say in relation to a new arms conference. It has no relation, as far as I can see, to any discussion about our debts am a good deal disturbed at the number of proposals that are being made about the expenditure of money."

These arid comments might be lightened by bits of humor or wry needling of the reporters.

"The Secretary of War has not resigned. I don’t expect he is going to, and I hope that for the sake of his peace of mind that his resignation will not be reported in the future oftener than once in two weeks. I don’t want to restrict the reporting but I think that would be often enough."

"I don’t recall any candidate for President who ever injured himself very much by not talking."

"I haven’t any specific reports about any states [in the campaign of 1924]. My reports indicate that I shall probably carry Northampton [his home town]. That is based more on experience."

Asked about a book which he hadn’t read, he was reminded of a reviewer who said he never read a book before he reviewed it, because it might prejudice him.

Asked about a General Hines, he said he wondered if it didn’t refer to a Major Hines. But in that case he was in the position of a man who was asked by a stranger for the location of a macaroni factory. The man asked if it might not be rather the noodles factory. The stranger agreed it could be. "Well, I don’t know where that is either."

These nuggets could not be quoted or ascribed. He kept reminding them of that. "It seems that it is necessary to have eternal vigilance to keep that from being done."

He often makes little jokes about the assiduous correspondents and their hard work. He suggests they ought to be paid more. He quips one day about "a great many questions today, but I find that many are duplicates or triplicates or other cates." He is pleased to find his chore thus lightened. But he is insistent on his anonymity. Stuck with this, the correspondents soon invented a "White House spokesman" as authority for what they gleaned from Mr. Coolidge. But Mr. Coolidge got on to that and scotched it.

"Of course it is a violation of the understanding to say that the spokesman said so and so and put in quotations on that. I think it would be a good plan to drop that reference to these conferences. It never was authorize done might as well say that the President said so and so it is perfectly apparent that when the word [spokesman] is used it means the President."

He then refused to let them use anything about his objection to the spokesman. "It was just said for the information of the conference. That part of the conference we will consider carried on in executive session." Thus he puts off-the-record even a reference to being off-the-record.

When he caught someone taking down his remarks in shorthand, he objected. "What I say here is not to be taken down in shorthand. Otherwise it interferes with my freedom of expression."

He objected at times to the way press conference information was used. "They are not in any sense interviews to be given out by the press, or statements but simply information that I give to the press in order that it may intelligently write reports and comments about the subjects that I dwell on."

He resolutely refused even such an occasional request of an exception as to quote his views on baseball, which must have struck the correspondents as unique.

(Here is Mr. Coolidge on baseball. This is August 1924, an exceptional season, for the Washington Senators are in contention as the pennant race comes down toward the wire.)

President: I suppose the Washington baseball team is the one that represents the whole nation. The others have some local claims. That which comes from the city of Washington, I suppose, represents the nation in its entirety more than any other team. If it should be so fortunate as to secure first place, in that respect I suppose it would be more agreeable to the whole nation than that which could be secured by having any local team win the pennant. I don’t know as I can make any statement about the present condition of our team that hasn’t been made by someone else. I am not an expert on baseball, though I enjoy the game. I haven’t made any plans yet about attending the World Series, but should that be the case I assume that it goes without saying that I would want to see the opening game.

Press: Mr. President, would it be permissible to quote that remark about baseball?

President: No, I don’t think so.

Withal, he claimed to enjoy these press sessions, and one can imagine it was a welcome change of pace, a chance to talk to people who weren’t after something, who were certainly a brighter and livelier crowd than the political hacks left to him by the Harding administration. And they might just happen to hit upon some question a President ought to be hep to.

Sometimes he even solicited their opinion, once when he was looking for a new Secretary of the Navy in place of Mr. Denby, whom he refused to fire for ceding the naval oil reserves to private interests but was certainly relieved to have resign. He told the reporters he wanted a good administrator, out of business. If they knew of one, he’d be glad of any suggestion. The ensuing appointment of Ray Lyman Wilbur was a press conference suggestion, according to the editors.

When he had to go to Gettysburg, he asked the correspondents’ judgment whether by train or car. Told the railroad was a rocky prospect, Coolidge opined that if they knew they had the press on board, the railroad should be apt to be solicitous in its service. As to what he was going to put into his inaugural address: "I don’t know. If any of you think of anything that ought to be covered, I should be obliged if you would suggest it."

Louis M. Lyons, former Nieman Curator, uses "The Talkative President: The Off-the-Record Press Conferences of Calvin Coolidge," as a springboard to write about the President and the press. The book is edited by Howard H. Quint and Robert H. Ferrell, University of Massachusetts Press.