How are great journalists made? Often, it’s pieces of great journalism that help form them, influencing their lives or careers in an indelible way. To celebrate the Nieman Foundation for Journalism’s 80th anniversary in 2018, we asked Nieman Fellows to share works of journalism that in some way left a significant mark on them, their work or their beat, their country, or their culture. The result is what Nieman curator Ann Marie Lipinski calls “an accidental curriculum that has shaped generations of journalists.”

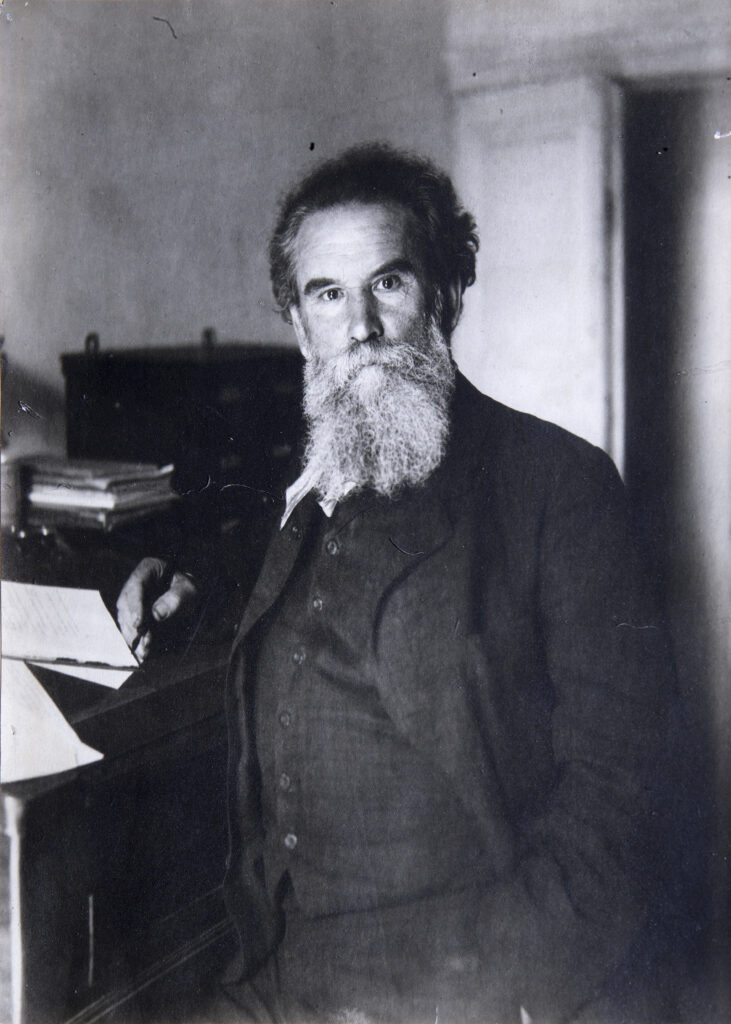

When I think about what influenced me as a journalist, a classic example of excellent Russian journalism—which is, I believe, extremely relevant now—comes to mind.

In an undergraduate class on the history of Russian journalism, I discovered the works of Vladimir Korolenko, a prominent journalist and human rights advocate during the early 20th century. I was particularly impressed by his series of publications on the high-profile anti-Semitic Beilis trial in 1913. In this trial, initiated by extreme nationalists and based on popular anti-Semitic sentiments, a Jewish man from Kiev, Menahem Mendel Beilis, was accused of the ritual murder of a child. Korolenko investigated the case and took a public stand in defense of Beilis. He also wrote an open letter titled “Call to the Russian People in regard to the blood libel of the Jews,” which many public intellectuals of the time signed. Korolenko’s actions played a significant role in the acquittal of Beilis.

Why did it strike me so deeply? Because it’s easy to be liberal and pro-diversity when it is mainstream. What is difficult is going against the mainstream. Uncovering a false accusation that has state power and public opinion behind it requires common sense, humanism, courage, and a readiness to go against the current.

Today, politicians and members of society still easily place all kinds of “bad guy” labels on groups of people whom they perceive as threats. And very few journalists have enough intelligence and courage to begin public discussions on whether these accusations are true. Since my student years, Vladimir Korolenko and his coverage of the Beilis trial has been a symbol of the principle that, as a journalist, you shouldn’t blindly accept the mainstream narrative, but instead subject it to verification according to universal human values.

The Beilis Case: The Jury Has Replied

By Vladimir Korolenko

Russkiye Vedomosti, Oct. 29, 1913

These selected excerpts translated from Russian by Alisa Sopova

Excerpt

Amid great tension, the Beilis trial is coming to its end. All the traffic around the court is blocked. Even street cars are not being let through. There are troops of mounted police and rangers on the streets. The requiem for the murdered baby Andryusha Yuschinsky is planned at 4 p.m. in St. Sophia Cathedral, with the bishop expected. From the street on which the court is located, a mob of people gathers at the cathedral. Here and there torches flare up over the crowd. Dusk is falling among an ominous disturbance.

The mood in the court grows even more tense, spreading out to the city.

Around 6 p.m. the reporters race out. The news spreads lightning fast that Beilis is acquitted. All of a sudden the mood on the streets changes. Multiple groups of people can be seen congratulating each other. Russians and Jews merge in common joy. The threat of a pogrom near the cathedral fades away