In newsroom argot, “Afghanistan-ism” is shorthand for stories about distant places that editors dismiss as irrelevant. In looking for the roots of 9/11 or our current war in Afghanistan, the dismissive word is now grimly ironic.

The starting point for any such inquiry, Roy Gutman, foreign editor for McClatchy Newspapers, tells us in his book-length exploration, is with our political leaders. In true bipartisanship they adopted the concept of Afghanistan-ism, if not the term itself. President Bill Clinton walked into the White House hoping not to be distracted by foreign affairs. He was, said former national security adviser Zbigniew Brzezinski in 1994, “the most disengaged president in my lifetime.” His administration vaguely understood and never formulated a sophisticated response to Osama bin Laden’s efforts to build a base in Afghanistan for his anti-American jihad.

As we are now painfully aware, the Bush administration was happy getting its hands dirty abroad. Even with this mindset—which assumed so much American power—it did not heed warnings that anticipated al-Qaeda attacks on our home soil. After being attacked and overreaching, the Bush team was outmaneuvered by bin Laden and the Taliban, who retreated into Afghanistan’s rugged mountains.

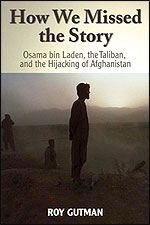

But Gutman does not excuse the press in his aptly named “How We Missed the Story: Osama bin Laden, the Taliban, and the Hijacking of Afghanistan.” The press’s failure, he argues, is “one of the greatest lapses in the modern history of the profession.” As the editor of Nieman Reports suggested when she asked me to write this essay, those lapses lend themselves to a broader discussion of foreign reporting and the increased potential for more of the same.

EDITOR'S NOTE

In the Spring 2007 issue of Nieman Reports, Gutman highlighted information from a chapter entitled “Silence Cannot be the Strategy” as part of the magazine’s collection of articles about the challenges journalists confront in reporting from Afghanistan.Gutman has a distinguished career—a Pulitzer Prize for International Reporting and a George Polk Award for foreign reporting—in covering difficult-to-report stories, such as his “ethnic cleansing” reporting in Newsday after the breakup of Yugoslavia. He uses those same skills in this book to surface poignant examples of news media failure.

One of the most telling is the bin Laden-supported massacre of some 2,000 villagers in Mazar-i-Sharif, a portentous event.Finding out what actually happened was a challenge that almost no journalist took on. One of the very few who did provided Newsweek with a well-documented story that editors squeezed into a brief in the “Periscope” section. In that issue of the magazine, the focus was on Clinton’s problems with Monica Lewinsky.

Foreign Reporting and Government Policy

“News organizations are free agents,” Gutman writes, “able to decide what to cover and how to cover it.” So, why do journalists find it so difficult to use that freedom to challenge government leaders who are reluctant to address pressing issues or, worse, are using all their powers to push an errant policy?

This isn’t a new problem. Basically stated, the executive branch has enormous control over the news agenda in foreign affairs, where public expertise is relatively limited. It sets policy and generally gets the last word in any debate. When the White House and Congress are mostly on the same page, as in the run-up to the Iraq War, journalists are constrained in introducing alternative points of view into their stories. Reporters never have to justify quoting an official. But quoting nonofficial naysayers starts to fall into the category of subjectivity. Why this naysayer and not that one?

Going against the official consensus thrusts journalists into the role of crusaders and, in the case of war, unpatriotic crusaders. “A great newspaper RELATED ARTICLES

"Foreign News Reporting: Its Past Can Guide Its Future"

- Jonathan Seitz

"George Weller Reported on World War II From Five Continents"

- Jan Gardneris to some extent a political institution,” former New York Times Managing Editor Turner Catledge once said. “To maintain its power it must use it sparingly.”

Journalism has inspiring examples of those who’ve bucked authority. One is the Times’ Harrison Salisbury with his reporting on the United States bombing of North Vietnam. His Pentagon-rattling stories revealed that, contrary to government pronouncements, the bombs hit civilian targets and that this only stiffened the enemy’s resolve. But Salisbury had to fight headwinds in his own organization and was denied a deserved Pulitzer Prize because he was seen as a traitor.

To understand why it might be more difficult now to deviate from the government line, it is useful to draw a comparison with the years between the world wars. Then, a wide range of media had an interest in foreign news—magazines, newspapers, several news services and, by the end of the period, fledgling radio. Correspondents, many of them freelancers who earned good livings, stayed overseas for years, acquiring expertise and operating with a great deal of independence. One of the best correspondents of this era was Vincent Sheean. In foreseeing the impending World War II, Sheean observed, “International journalism was more alert than international statesmanship.”

Today, there are few Sheeans. Correspondents go abroad in smaller numbers and tend not to stay as long. Some have great expertise, but the number of those who do is relatively smaller than it was. As important—and this development has not received enough attention—correspondents operate on a much shorter leash.

Until recently, The (Baltimore) Sun was one of many newspapers with distinguished if modest-sized foreign services. Part of the tradition, embodied in one of its well-respected managing editors, Buck Dorsey, was that correspondents were on their own. He typically responded to requests for guidance this way: “Please stop asking me to write letters. Love, Dorsey.” This attitude of giving foreign reporters a freer rein was typical of many newspapers.

Correspondents considered such editorial independence a perk and affectionately remembered the editors who granted it. In reality, though, editors had little choice. They could not have controlled correspondents if they had wanted to. International telephone lines did not work well enough.

The New News Cycle

Now, with modern satellite communication and the ability to file stories instantly, correspondents can be in touch with the home office all day long, if the editor wants them to be— and typically they do. “We now live in a nanosecond news cycle,” David Hoffman, assistant managing editor for foreign news at The Washington Post, explained to me recently. Reporting from afar now means being an “information warrior.” The Post’s correspondents write first and often for the Web and then for the paper. In view of space shortages in the newspaper, stories destined for print must be carefully crafted. Unless the news from overseas demands scarce real estate in the next day’s paper, Hoffman has to plan to get foreign news into the paper. Each day he tries to have phone conversations with two of his correspondents. And he expects a Monday memo outlining their plans, which he will modify. It’s not like the old days, he said, when whatever a correspondent sent in was published.

The result is that the agenda for correspondents is more frequently set by editors, whose agenda is set by other news media (“quick, match that”) and is collectively more in tune with Washington than, say, Kabul. The Washington Post’s Jonathan Randal described how, during the first Iraq War, his paper’s “top brass … convinced themselves they had a better overall grasp of events than their men on the spot and wrote the overall lead story from Washington,” among other things overstating the accuracy of so-called “smart” bombs.

“I unashamedly pine for the old cable office or the telex in the Third World that shut down at nightfall in the 1950’s and 1960’s and allowed me to get drunk or read poetry without fear of an editor’s intrusion until the next morning,” Randal added. “That free time also allowed me time to meet and read about the people I was covering.”

The improved ability to communicate has pluses. Editors create better-coordinated packages of foreign reporting. No longer do they need to worry that free-roaming correspondents will trip over each other, as happened during the 1950s when three of the Sun’s foreign correspondents assigned themselves to cover the same Geneva summit meeting. Better communication also has facilitated the rise of new types of correspondents who offer some promise for improving the flow of news. A prime example is GlobalPost, a Boston-based enterprise that recently began to deliver articles, photographs, video and audio over the Web by drawing on contract correspondents on the ground around the world.

Some of these freelancers are foreign journalists, which is part of another trend. With increasing frequency, traditional and new media are relying on local journalists who have deep knowledge of their country. But it is far from a given that these new approaches will automatically override the power of editors to manage news to fit a preconceived agenda. To make a decent living, freelancers and stringers need to be particularly sensitive to editors’ expectations.

The problems presented by improved communications are as old as the telegraph. In the mid-19th century, William Howard Russell foreshadowed the laments of modern reporters who must first write quickly for the Web. “I cannot explain to you,” Russell wrote his editor at The Times of London, “the paralyzing effects of sitting down to write a letter after you have sent off the bones of it by lightning.” Speed and efficiency, a hallmark of assembly-line production, do not produce the most profound journalism.

Foreign news reporting is not predictable in the way White House news briefings are. Gathering news entails a trial-and-error process of ferreting out facts and impressions. Having independence and the time to exercise it are especially critical for foreign correspondents whose job is to make sense of a wide range of issues, bearing in mind the cultural and political context of the place and time, and then figure out how to convey this information to an American audience. It is essential—really a matter of national security—for correspondents to test government assumptions by independently gathering facts and analyzing trends that policymakers might have missed or may ignore.

“Obscure, faraway conflicts have given rise to the evils of this era … as well as the seeds of far bigger wars,” Gutman warns in writing about the perils of Afghanistan-ism. The precipitous decline in the number of correspondents reporting for traditional news media should concern us, but as Gutman’s book reminds us, it is also the content of this reporting that has been worrisome in recent years. As we look ahead, those journalists sending foreign news to an American audience—whether they work for newspapers, TV, radio or digital media—need to do their work independent of pressure from political forces back home. What serves us best is when these men and women are not domestic reporters working abroad but true foreign correspondents.

John Maxwell Hamilton is a longtime journalist and dean of the Manship School of Mass Communication at Louisiana State University. His latest book, “Journalism’s Roving Eye: A History of American Foreign Reporting,” was published in September.

The starting point for any such inquiry, Roy Gutman, foreign editor for McClatchy Newspapers, tells us in his book-length exploration, is with our political leaders. In true bipartisanship they adopted the concept of Afghanistan-ism, if not the term itself. President Bill Clinton walked into the White House hoping not to be distracted by foreign affairs. He was, said former national security adviser Zbigniew Brzezinski in 1994, “the most disengaged president in my lifetime.” His administration vaguely understood and never formulated a sophisticated response to Osama bin Laden’s efforts to build a base in Afghanistan for his anti-American jihad.

As we are now painfully aware, the Bush administration was happy getting its hands dirty abroad. Even with this mindset—which assumed so much American power—it did not heed warnings that anticipated al-Qaeda attacks on our home soil. After being attacked and overreaching, the Bush team was outmaneuvered by bin Laden and the Taliban, who retreated into Afghanistan’s rugged mountains.

But Gutman does not excuse the press in his aptly named “How We Missed the Story: Osama bin Laden, the Taliban, and the Hijacking of Afghanistan.” The press’s failure, he argues, is “one of the greatest lapses in the modern history of the profession.” As the editor of Nieman Reports suggested when she asked me to write this essay, those lapses lend themselves to a broader discussion of foreign reporting and the increased potential for more of the same.

EDITOR'S NOTE

In the Spring 2007 issue of Nieman Reports, Gutman highlighted information from a chapter entitled “Silence Cannot be the Strategy” as part of the magazine’s collection of articles about the challenges journalists confront in reporting from Afghanistan.Gutman has a distinguished career—a Pulitzer Prize for International Reporting and a George Polk Award for foreign reporting—in covering difficult-to-report stories, such as his “ethnic cleansing” reporting in Newsday after the breakup of Yugoslavia. He uses those same skills in this book to surface poignant examples of news media failure.

One of the most telling is the bin Laden-supported massacre of some 2,000 villagers in Mazar-i-Sharif, a portentous event.Finding out what actually happened was a challenge that almost no journalist took on. One of the very few who did provided Newsweek with a well-documented story that editors squeezed into a brief in the “Periscope” section. In that issue of the magazine, the focus was on Clinton’s problems with Monica Lewinsky.

Foreign Reporting and Government Policy

“News organizations are free agents,” Gutman writes, “able to decide what to cover and how to cover it.” So, why do journalists find it so difficult to use that freedom to challenge government leaders who are reluctant to address pressing issues or, worse, are using all their powers to push an errant policy?

This isn’t a new problem. Basically stated, the executive branch has enormous control over the news agenda in foreign affairs, where public expertise is relatively limited. It sets policy and generally gets the last word in any debate. When the White House and Congress are mostly on the same page, as in the run-up to the Iraq War, journalists are constrained in introducing alternative points of view into their stories. Reporters never have to justify quoting an official. But quoting nonofficial naysayers starts to fall into the category of subjectivity. Why this naysayer and not that one?

Going against the official consensus thrusts journalists into the role of crusaders and, in the case of war, unpatriotic crusaders. “A great newspaper RELATED ARTICLES

"Foreign News Reporting: Its Past Can Guide Its Future"

- Jonathan Seitz

"George Weller Reported on World War II From Five Continents"

- Jan Gardneris to some extent a political institution,” former New York Times Managing Editor Turner Catledge once said. “To maintain its power it must use it sparingly.”

Journalism has inspiring examples of those who’ve bucked authority. One is the Times’ Harrison Salisbury with his reporting on the United States bombing of North Vietnam. His Pentagon-rattling stories revealed that, contrary to government pronouncements, the bombs hit civilian targets and that this only stiffened the enemy’s resolve. But Salisbury had to fight headwinds in his own organization and was denied a deserved Pulitzer Prize because he was seen as a traitor.

To understand why it might be more difficult now to deviate from the government line, it is useful to draw a comparison with the years between the world wars. Then, a wide range of media had an interest in foreign news—magazines, newspapers, several news services and, by the end of the period, fledgling radio. Correspondents, many of them freelancers who earned good livings, stayed overseas for years, acquiring expertise and operating with a great deal of independence. One of the best correspondents of this era was Vincent Sheean. In foreseeing the impending World War II, Sheean observed, “International journalism was more alert than international statesmanship.”

Today, there are few Sheeans. Correspondents go abroad in smaller numbers and tend not to stay as long. Some have great expertise, but the number of those who do is relatively smaller than it was. As important—and this development has not received enough attention—correspondents operate on a much shorter leash.

Until recently, The (Baltimore) Sun was one of many newspapers with distinguished if modest-sized foreign services. Part of the tradition, embodied in one of its well-respected managing editors, Buck Dorsey, was that correspondents were on their own. He typically responded to requests for guidance this way: “Please stop asking me to write letters. Love, Dorsey.” This attitude of giving foreign reporters a freer rein was typical of many newspapers.

Correspondents considered such editorial independence a perk and affectionately remembered the editors who granted it. In reality, though, editors had little choice. They could not have controlled correspondents if they had wanted to. International telephone lines did not work well enough.

The New News Cycle

Now, with modern satellite communication and the ability to file stories instantly, correspondents can be in touch with the home office all day long, if the editor wants them to be— and typically they do. “We now live in a nanosecond news cycle,” David Hoffman, assistant managing editor for foreign news at The Washington Post, explained to me recently. Reporting from afar now means being an “information warrior.” The Post’s correspondents write first and often for the Web and then for the paper. In view of space shortages in the newspaper, stories destined for print must be carefully crafted. Unless the news from overseas demands scarce real estate in the next day’s paper, Hoffman has to plan to get foreign news into the paper. Each day he tries to have phone conversations with two of his correspondents. And he expects a Monday memo outlining their plans, which he will modify. It’s not like the old days, he said, when whatever a correspondent sent in was published.

The result is that the agenda for correspondents is more frequently set by editors, whose agenda is set by other news media (“quick, match that”) and is collectively more in tune with Washington than, say, Kabul. The Washington Post’s Jonathan Randal described how, during the first Iraq War, his paper’s “top brass … convinced themselves they had a better overall grasp of events than their men on the spot and wrote the overall lead story from Washington,” among other things overstating the accuracy of so-called “smart” bombs.

“I unashamedly pine for the old cable office or the telex in the Third World that shut down at nightfall in the 1950’s and 1960’s and allowed me to get drunk or read poetry without fear of an editor’s intrusion until the next morning,” Randal added. “That free time also allowed me time to meet and read about the people I was covering.”

The improved ability to communicate has pluses. Editors create better-coordinated packages of foreign reporting. No longer do they need to worry that free-roaming correspondents will trip over each other, as happened during the 1950s when three of the Sun’s foreign correspondents assigned themselves to cover the same Geneva summit meeting. Better communication also has facilitated the rise of new types of correspondents who offer some promise for improving the flow of news. A prime example is GlobalPost, a Boston-based enterprise that recently began to deliver articles, photographs, video and audio over the Web by drawing on contract correspondents on the ground around the world.

Some of these freelancers are foreign journalists, which is part of another trend. With increasing frequency, traditional and new media are relying on local journalists who have deep knowledge of their country. But it is far from a given that these new approaches will automatically override the power of editors to manage news to fit a preconceived agenda. To make a decent living, freelancers and stringers need to be particularly sensitive to editors’ expectations.

The problems presented by improved communications are as old as the telegraph. In the mid-19th century, William Howard Russell foreshadowed the laments of modern reporters who must first write quickly for the Web. “I cannot explain to you,” Russell wrote his editor at The Times of London, “the paralyzing effects of sitting down to write a letter after you have sent off the bones of it by lightning.” Speed and efficiency, a hallmark of assembly-line production, do not produce the most profound journalism.

Foreign news reporting is not predictable in the way White House news briefings are. Gathering news entails a trial-and-error process of ferreting out facts and impressions. Having independence and the time to exercise it are especially critical for foreign correspondents whose job is to make sense of a wide range of issues, bearing in mind the cultural and political context of the place and time, and then figure out how to convey this information to an American audience. It is essential—really a matter of national security—for correspondents to test government assumptions by independently gathering facts and analyzing trends that policymakers might have missed or may ignore.

“Obscure, faraway conflicts have given rise to the evils of this era … as well as the seeds of far bigger wars,” Gutman warns in writing about the perils of Afghanistan-ism. The precipitous decline in the number of correspondents reporting for traditional news media should concern us, but as Gutman’s book reminds us, it is also the content of this reporting that has been worrisome in recent years. As we look ahead, those journalists sending foreign news to an American audience—whether they work for newspapers, TV, radio or digital media—need to do their work independent of pressure from political forces back home. What serves us best is when these men and women are not domestic reporters working abroad but true foreign correspondents.

John Maxwell Hamilton is a longtime journalist and dean of the Manship School of Mass Communication at Louisiana State University. His latest book, “Journalism’s Roving Eye: A History of American Foreign Reporting,” was published in September.