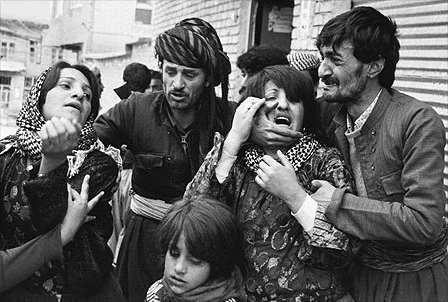

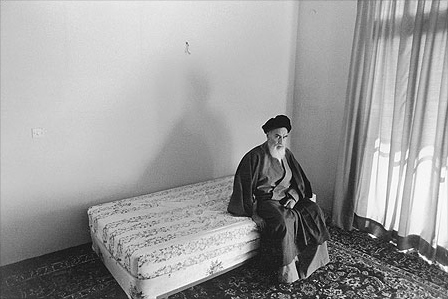

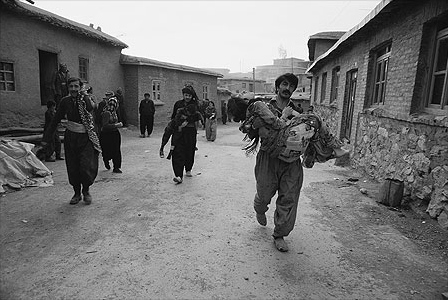

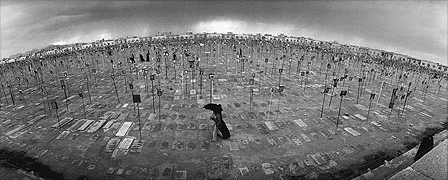

In the mid-1960’s, Reza Deghati taught himself the principles of photography as a 14 year old living in Tabriz, Iran. During the early 1970’s, his pictures were of rural society and architecture, which he then studied at the University of Tehran. The Islamic Revolution in 1979 shifted Reza’s focus to the city, where he covered the conflict for Agence France-Presse and Sipa Press. Reza, who uses only his first name, then photographed events in Iran for Newsweek until 1981, when he fled Iran after being forced into exile. In the nearly 30 years since then, Reza has traveled throughout the Middle East and Asia, and into Africa and Europe, and had his work published primarily in National Geographic. “I have been using my camera as a tool to bear witness,” he writes. In Afghanistan, Reza founded a nonprofit organization, Aina, through which he has supported the development of independent media and fostered cultural expression. In 2008, National Geographic’s Focal Point published “Reza War + Peace: A Photographer’s Journey,” and Reza has generously contributed photographs he took in Iran in 1979 and 1980 to our project. His words accompany the photos that follow.