The world belongs to you. |

Few events of the 20th century have so dramatically engulfed such a large proportion of humanity as the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution. Millions suffered and an untold number of others died, yet the Cultural Revolution remains only barely understood. There is little agreement on when it began (1964 or mid-1966), how long it lasted (three years, 1966-69, or a decade, 1966-76), what it was about (culture, revolution, power struggles, or Mao Zedong’s monomania), or what it achieved (a true Marxist-Leninist revolution, the prelude to the reform era, or just a meaningless period of political zealotry and chaos).

This time in China’s history presents serious challenges to conventional historians, who work primarily with words. But for documentary filmmakers the challenge is greater, for we rely on images to render the past. One of the most difficult problems we faced in making “Morning Sun”—a film about the Cultural Revolution—was the lack of archival footage from this period. And what was available (with few exceptions) told the story from a single perspective—that of the government. At that time, there was no film equipment in private hands, and cameramen working for state-owned studios were required to register the film stock they took and return every roll of film after their job was done.

In making “Morning Sun,” we grappled constantly with the issue of how to tell complex stories with limited visual data. We made choices that maximized the strength of film as a medium to convey history. “Morning Sun” is, therefore, not a chronological and comprehensive recounting of political events of the period (most of which left very little visual record), but rather an inner history of the age of the Cultural Revolution. We weave together diverse personal stories with period footage, relying heavily on cultural productions of that time to chart the psychological and emotional topography of high-Maoist China. We provide a multiperspective view of a tumultuous period as seen primarily through the eyes of people who came of age during the 1960’s, and we reveal the complex motivations behind their actions.

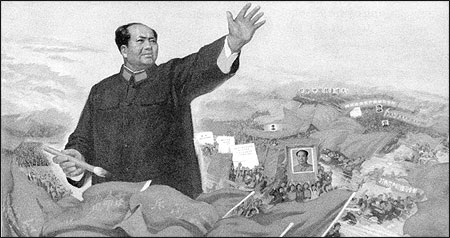

This is a 1967 poster celebrating a short essay Mao Zedong circulated within a major Party Conference in August 1966, entitled, “Bombard the Headquarters: My Big Character Poster.” In the essay, he directed scathing criticism towards “certain party leaders” for suppressing the masses and obstructing the Cultural Revolution. Although Mao didn’t write the essay with a brush but scribbled it on the margins of an old Beijing Daily, the image of Mao wielding a brush and changing the course of history captured popular imagination. Numerous posters, woodcuts, oil paintings, and traditional Chinese style paintings portrayed Mao in this heroic pose.

Two Films Frame the Mental Landscape

Throughout “Morning Sun” we use feature films from the 1950’s, 60’s and 70’s, to echo the mental landscape of the young generation that participated in the Cultural Revolution. We use two films, in particular, to act as a framing and commentary device. In addition to representing specific historical events in “Morning Sun,” these two films— “The East is Red” and “The Gadfly”—serve as historical metaphor and provide a narrative structure for our film.

“The East is Red” is a film version of a musical extravaganza that was produced in 1964 for the 15th anniversary of the founding of the People’s Republic of China. It featured Mao as the singular, ever-victorious and unassailable leader of China’s 20th century revolutionary struggle, eclipsing all other leaders in its colorful narrative. A significant milestone in the ascendancy of the Mao cult, it foreshadowed the ever more blatant rewriting of history by those in power in the ensuing years. While it was being staged another revolution was getting underway.

Young audiences who watched “The East is Red” would go on to become Red Guards. They wanted to re-enact the kind of revolution that was depicted in that movie. Those we interview in our film speak of the profound impact the film had on them, as they sought to give their lives meaning by connecting with something larger than themselves. For them, revolution, as part of the Marxist concept of “the law of history,” was tantamount to religious faith. “Morning Sun” repeatedly returns to scenes from “The East is Red” as it follows personal stories of these young people, evoking the complex relationship between the fictional stage and the historical stage, between play actors and historical actors.

“The Gadfly,” a 1955 Soviet film that was dubbed into Chinese, was based on the novel of the same name by the English author Ethel Lilian Voynich, published in 1897. The novel, also translated into Chinese, enjoyed an unrivalled place in the hearts and minds of young participants in the Cultural Revolution. Almost everyone we interviewed named “The Gadfly” as one of the two or three most influential books during their formative years. The innocent and wide-eyed romantic, Arthur, who becomes a battle-scarred revolutionary, the Gadfly, struck a profound chord with the adolescents of China.

Over the years, however, as they experienced the revolution for themselves, the meaning of the book changed. In their earlier, simpler reading, the Gadfly’s eventual rejection of the Catholic Church and his dedication to the revolutionary cause fit well with the teachings of the Communist Party. Later, however, they began to see parallels between the Catholic Church (exemplified by the ambitious and unprincipled Cardinal Montanelli, the closeted father of Arthur) and the Communist Party (and the ultimate father figure of the Chinese revolution, Mao Zedong). The same heroism embodied in the figure of the Gadfly now became an inspiration that sustained many young people in their resistance against the tyranny of the Party.

The theme of parent and child is also played out on another level through a 20-year saga of rejection and reconciliation between Li Nanyang and her father, Li Rui, Mao’s one-time secretary who was denounced and sent into exile when his daughter was nine years old. One key element of “Morning Sun” is its tracing of a parallel narrative of the personal and the cultural-political trajectories of the Cultural Revolution era. We do this by using the Gadfly’s story as a multifaceted metaphor.

Through using “The East is Red” and “The Gadfly,” as well as many other film and stage productions, “Morning Sun” demonstrates the cultures and convictions that created the language, style and content of a mass movement. The films and plays, the music and ideas, the frustrations and fantasies, as well as the rhetoric and the ideologies are at the heart of a story about a new revolution that attempted to remake revolution itself. It is a film about the promise of a secular form of the sublime and how that promise and its frustration have created the China of the 21st century.

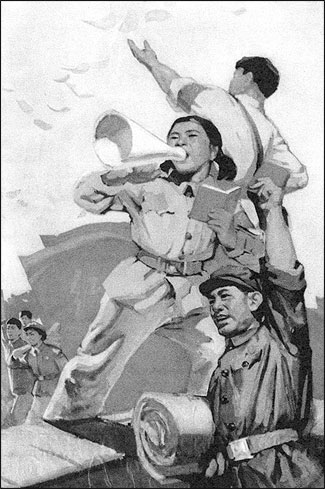

This is a 1967 poster depicting Red Guards speaking through a megaphone and distributing leaflets. Their poses are part of a standard iconography that run through many different forms of revolutionary art, including films, plays, paintings and sculpture. This type of pose became the body language that was embraced by many young enthusiasts during the Cultural Revolution, in a process of life imitating art.

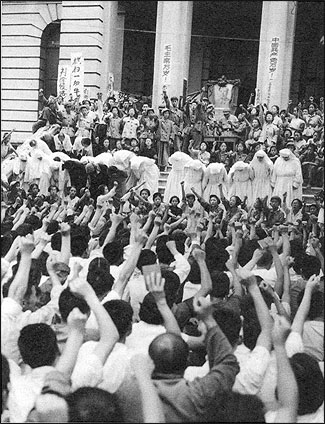

Red Guards denounce a group of Franciscan nuns in front of their desecrated church in late August 1966. The nuns were expelled from China with great fanfare a few days later. These nuns had remained in China after the Communist victory in 1949. They ran an English school, which many children from Western embassies attended. During the Cultural Revolution their presence in China became evidence to the Red Guards that the revolution was not thorough enough.

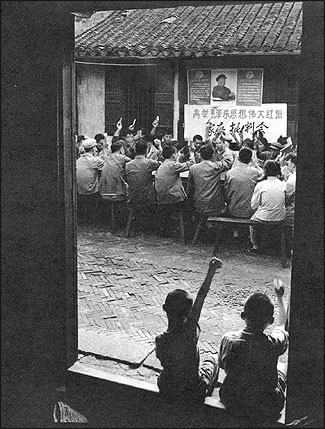

In a 1967 photograph, workers of the Shanghai No. 3 Steel Mill attend a meeting held in their neighborhood to denounce “China’s Khrushchev,” the term used to describe head of state, Liu Shaoqi, before the official press printed his real name in denunciation pieces. The banner behind the table reads, “Family Repudiation Meeting.”

Carma Hinton, who produced and directed “Morning Sun” with Geremie Barmé and Richard Gordon, was also the interviewer (in Chinese) for the film. She was born in Beijing in 1949 and lived there through the early years of the Cultural Revolution. Her other films include “The Gate of Heavenly Peace” (with Gordon and Barmé), which won a George Foster Peabody Award, “Abode of Illusion,” and a three-part series, “One Village in China” (with Gordon.) This essay is based on contributions made by all three directors of “Morning Sun.”