Ugandan President Yoweri Museveni. Photo by Peter Busomoke/The Monitor.

When I read The Sunday Monitor on the morning of September 21, 1997, my heart skipped a beat. A screaming headline proclaimed: “Kabila Paid Uganda In Gold—Says Report.” The Monitor’s senior reporter, Andrew Mwenda, wrote the story. On that Sunday, Mwenda was just 12 days shy of his 25th birthday. At that early age, he was already clearly the top political reporter in the country.

I met up with the editor of The Sunday Monitor on Monday morning and joked about how his lead story was going to send me to jail. (I am Editor of The Monitor, so under Ugandan law I have legal responsibility for what appears in any edition of the paper.) The story was based on a report in a Paris-based publication, The Indian Ocean Newsletter. That paper had reported that the government of the new President of Zaire, renamed Congo, Laurent Kabila, had paid Uganda in gold for “services rendered” to his rebels when he was fighting to oust the Mobutu Sese Seko dictatorship. “Services rendered” was a reference to the military support that Uganda had given the anti-Mobutu rebels during the war.

My unease was not about the facts. In any case, the story gave prominence to responses from two government officials, one of them a minister, denying that Congo had paid Uganda. It was the politics of it that worried me; the conclusion one was likely to draw was that the Ugandan government had become a mercenary outfit and had helped oust Mobutu not out of a noble aim to take out a dictator, but to earn money from the enterprise.

My fears about being sent to jail were realized a week later. President Yoweri Museveni, speaking at a military parade, went ballistic. He swore that The Monitor would pay for the story and that we must go to jail for it. Uganda is not a conventional democracy. The president still has the powers of an 18th Century king. And what he asks for, he gets.

Two days later, the police came to our offices to take statements. On October 24, Mwenda and I were served with criminal summons to appear in the chief magistrate’s court. Though we drove ourselves to court, immediately upon our arrival we were bundled off to filthy holding cells near the court, which were overcrowded with common criminals.

After about an hour, we were taken out to a rather bizarre court session. We were charged with “publication of false news” under Section 50 (1) of the Penal Code. This is punishable upon conviction by two years in jail. Our lawyer was the city’s most well-known “new breed” of lawyer, but nevertheless the magistrate asked him to produce his law certificate. Thirty minutes went by before the certificate was brought from our counsel’s office. The hours were ticking perilously close to 5 o’clock, when the courts closed.

We pleaded innocent. Among other things, the magistrate slapped a record bail of $2,000 on each of us. That is a lot of money in a country where the per capita income is $300. More significantly, it was the highest bail ever demanded for a misdemeanor, and the prosecution hadn’t even “opposed” bail. (In Uganda, the accused applies for bail and the prosecution can either oppose the application or choose not to contest it. It is extremely rare for a magistrate to impose a cash bail in instances where the prosecution hasn’t raised objections.) Our $2,000 bail was even higher than had been set for anyone who had been granted bail for rape, defilement, theft and, in a few cases, murder. The magistrate must also have known that hardly anyone carries that amount of money in cash. And though The Monitor could raise $4,000 for the two of us, the banks had closed three hours earlier.

In a strange request, the magistrate ordered that the people who stood as our sureties produce legal documents indicating that they were residents at the addresses they had given. As it was a Friday, it seemed a common trick pulled by the government was working itself through this partisan magistrate. The conditions of the bail were so stiff that it was unlikely that we would meet them in the 30 minutes that were left before the court closed. The result would then have been a weekend in jail before we appeared in court Monday morning. When courts close, the prisoners—and all people like us whose cases are not concluded for the day—are herded under heavy security into buses and vans and driven off to a sprawling “maximum” prison in the suburbs of the city.

Our magistrate was, however, foiled by a piece of modern technology and wiliness of journalists. We had been escorted out of court and were sitting in the cells waiting for the guards to come. It was nearly 6 p.m., and the bus should have left an hour back. Everyone was puzzled about the delay. It turned out that dozens of journalists had come to the court and, through means that we are bound never to reveal, caused the delay of the bus’s departure. And as soon as we had left the courtroom, our colleagues and lawyers went to work on their cell phones to contact bank managers. The $4,000 in cash was brought to the court just after five and paid into the cash office.

On Monday, we began to fight back. We petitioned the High Court against the outrageous bail. Our argument was simple. To publish something that annoys the President cannot be worse than murder and rape. We won and got our money back. The bail was lowered to $200 for each of us.

Then we took the unprecedented step and petitioned the Constitutional Court. The Constitutional Court is a very awesome place, and there have been times in the past when it did not receive a single petition for two years. Our petition argued that the laws in the Penal Code that made criminal the act of publication were archaic and a violation of the democratic principles set out in the new constitution (1995).

Our audacity paid off. The Constitutional Court met to hear our voluminous petition. But we emerged with only a half-victory. It refused to hear our arguments, arguing that our human rights had not yet been violated, since the lower court had not disposed of our case. In other words, until the magistrate’s court had sent us to prison or acquitted, we had no case. And unless we went through the trial, we could not complain that we shouldn’t have been tried. The consolation was that they agreed to hear our petition once the lower court was done, whether or not we lost the case.

We had never understood why the “court system” was so dreaded until we entered it. On our next court appearance, the chief magistrate who had been given so much trouble was not on the case. A new one had been assigned. Then, on our third appearance, we found the case had again been reassigned.

In the end, it went through five magistrates. In a court system where there are no juries, who sits as the magistrate is critical. And what it meant in our case was that no single magistrate could acquire an overall picture of the case, nor receive firsthand testimony about the evidence. Each successive one would have to rely on reading about the endless evidence. Also, if the state has a bad time during some points in the trial, it can salvage its case by putting together a powerful summation. This would be far more influential for a magistrate who came in at the tail end and has had none of the previous argument, than it would for one who had been with the case all the way. Worse, it throws the defense in some disarray by forcing it to keep shifting tactics with every change of magistrate.

Between October 24, 1998 and February 16, 1999, when the case before these magistrates ended, we made 33 trips to the court. We therefore had to get 33 bail extensions. Going through that made our lives very difficult. I found that we watched every story we published and every action we did very carefully, lest it lead to an application by the state to cancel our bail or to pile on new charges.

We could not travel outside the city without discussing it with our lawyers. All our travels abroad during that period were built around the next trial. We had to be careful to build in several days to provide for various flight cancellations, just to ensure that we didn’t miss court dates. We lost control of our schedules.

On February, Magistrate Margaret Tibulya acquitted us in a remarkably brave ruling for an officer of the court at that level. Good political judgment, luck, smart defense lawyers, and the traditional difficulties for state prosecutors in handling criminal cases against the media helped our cause immensely.

Early in meetings with our lawyers, we concluded that the best strategy was to lower the political temperature around the story. In order to do that, we chose the risky path of discouraging several international press freedom groups from mounting any protest campaigns against our troubles. This was a slippery plan because in the majority of such cases in the Third World where media freedoms are not well established, international protests by the world press freedom groups have been instrumental in embarrassing anti-free press governments into releasing and dropping cases against journalists.

We also had one of The Monitor’s reporters and an attorney travel to Kinshasa to get more evidence. We were pleasantly surprised to find that a crusading independent newspaper, Le Potentiel, had published a story on September 17, 1997, detailing how much, according to what it alleged were official records, each of the countries that had supported Kabila to take power, including Uganda, had been paid in war reparations. We were also able to get a statement that had been issued by the Congolese mining authority explaining that it was not forwarding enough money to the military to pay the recently victorious soldiers because it was taking care of Kabila allies. Therefore if push came to shove, we would argue truth.

Our plan A however was to push the point that whether the Uganda government was paid in gold, or paid at all, was not critical to the case. Section 50 (1) seeks to punish not just false information, but says that it must “also cause public alarm.” Our lawyers held that it was not the intention of the makers of the law to punish all false news. For example, no journalist would be charged with publishing false news if he or she misreported the goals a rival team scored against the national soccer team in an international match—something that might indeed cause a measure of “public alarm.”

The law, according to our lawyers, intended to punish only falsehoods that were “very substantial.” The most important aspect was therefore not falsehood, but public alarm. The prosecution found it easier to prove falsehood than alarming the public, so they concentrated on that. They paid dearly for that tactical mistake. And they made their case worse by relying exclusively on state employees as their witnesses.

Secondly, the charges arose out of two sentences, in a story that had 60 sentences. The prosecution had to prove that the “statement” in issue was false. Our defense therefore argued that the “statement” was the whole story, not just two sentences, and that none of the state witnesses claimed to have read only the two contentious parts. All of them had read the whole story. Therefore if the “statement” was the whole story, then the prominent comments by the government minister and officials that indeed there had been no payment could not be ignored.

Thirdly, our side argued that there was nothing wrong with being paid, as long as the service was not of a criminal nature. The magistrate ruled that the prosecution and its witnesses had proved that there had been no payment in gold to Uganda. She went on to point out that the same point had been made by the government officials who we quoted in the story. However, she ruled that the state had failed to prove that any aspect of the story had caused public alarm. She noted that instead one of the state witnesses, a manager with the central bank, said that if indeed there had been a payment, then she would have been “very happy,” because it would have improved the country’s gold reserves.

Finally, she also found that “handpicked” government employees, who had no option under the terms of their employment except to defend the state, were not credible witnesses in a case in which “public opinion” was supposed to be the benchmark for proof. Therefore she acquitted us.

During the trial, Uganda and Rwanda had turned against President Laurent Kabila, whom they had helped overthrow Mobutu in May 1997. Museveni acknowledged in several statements that Uganda had indeed given Kabila military aid, and he had now become an ingrate who was biting the hand that feeds him. Kabila and his ministers kept denouncing Uganda, claiming that its soldiers had gone bad, and Ugandan troops in DR Congo were no longer liberators but had turned into rogues who were looting the country’s minerals and timber.

This fed a lot of media and public interest in our case, because we were seen as being persecuted for telling the truth. The independent FM stations in Kampala, in particular, followed the trial closely. Beside the news value, they had a selfish interest. The case was a popular subject of radio talk shows and jokes mocking the government, so the stations often covered it in order to supply the raw material for the evening’s phone-ins. In the state media, meanwhile, Mwenda and I were denounced as conniving traitors who had recklessly caused the story to be published in order to become “martyrs.” Overstated, perhaps, but it can’t be denied that we became small stars; we signed quite a handful of autographs, and the service we received in most restaurants where we went was always very good.

We were saved by the fact that the reporter called two government officials—and the Sunday Editor let their denials stand, uninteresting as they were. That was something the prosecutors couldn’t get around.

The lesson here is an old one. It is good journalism to give the other side its say, however little it might seem to add to the story. This could turn out to be the only thing that a lawyer can use to keep you out of jail.

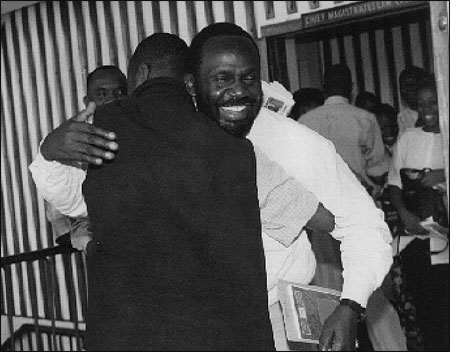

Onyango-Obbo and Mwenda (back to camera) after their acquittal February 16, 1999. Photo by John Nsimbe/The Monitor.

Charles Onyango-Obbo is a 1992 Nieman Fellow and Editor of The Monitor in Uganda.