Tan southwest homes gave way to desert as Interstate 10 took us out of Phoenix, and I couldn’t help but dwell on the voice mail greeting I’d recorded the day before from my desk in Crystal Lake, Illinois. “I will be out on assignment ….”

It’s a phrase I’d never uttered in seven years with the Northwest Herald, a small paper in McHenry County, Illinois, two of them as the newspaper’s senior reporter. In these trying times for newspapers, talking the editors of a 38,000-circulation daily into two plane tickets and two hotel rooms is worthy of a story in and of itself.

Sitting in the passenger seat on the sunny October 2007 day was Danielle Guerra, a 22-year-old videographer and Vanderbilt University graduate, whose persistence was one of the reasons for the trip. And ahead of us on I-10 was an interview that we both wanted and dreaded to conduct. Waiting in that Phoenix suburb was Joanne Branham, who lived much of her life in the small town of McCullom Lake, nestled in McHenry County, a county northwest of Chicago. She and her husband of 44 years, Franklin, had moved to Arizona after raising five children to spend their sunset years somewhere warm.

But that was not to be—Franklin died in 2004 of glioblastoma multiforme brain cancer, a deadly disease that afflicts slightly more than three people per 100,000. That wasn’t the main reason Danielle and I hopped on a plane. Months after Franklin’s diagnosis, two of his former next-door neighbors in McCullom Lake were diagnosed with brain cancer as well. All three families in April 2006 sued two manufacturers, Rohm and Haas and Modine Manufacturing, located a mile north of their homes in the neighboring village of Ringwood. For decades, consultants had tracked a plume of volatile organic chemicals in the groundwater from their operations.

After more than a year of covering the issue piecemeal, Guerra and I convinced our editors to let us pursue what turned into a six-part investigation full-time, also atypical for such a small-size newspaper. By the day of our trip, 22 current and former residents, all but four with brain and nerve cancer, had sued the companies.

One of my favorite proverbs from a book of sayings that my late father kept in his study was that age and treachery will always overcome youth and skill. But whoever came up with that bromide never examined what could happen if you merged the two—Guerra’s youth and skill and my age and treachery—toward a common goal. The two of us—and the Northwest Herald—banked our reputations on the answer.

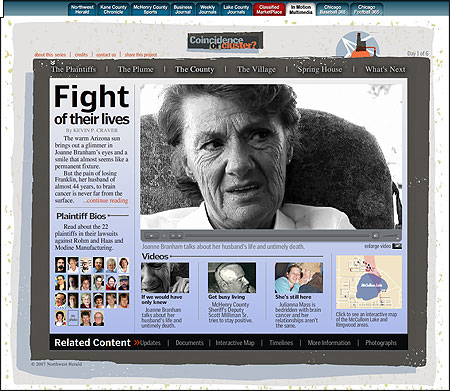

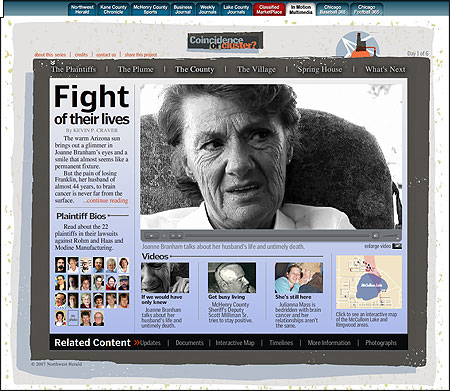

In the multimedia presentation of this story, Joanne Branham expresses profound sadness about her husband’s death from a glioblastoma multiforme brain tumor that she and other families similarly affected believe was caused by industrial contaminants near their home in McCullom Lake, Illinois.

Moving Pictures

I had worked on stories with multimedia components before embarking on this series, but nothing this ambitious. Guerra and I agreed at the beginning that every story in the series would have accompanying video, and I attended almost every interview or shoot that she conducted. I quickly learned of multimedia’s potential—its raw power to reach out and grab viewers by the collar and not let them go.

Arizona’s climate had been good to Joanne Branham. She was healthier than many people half her age, and she had the energy to manage a restaurant, where patrons affectionately called her “Aunt Jo.” Guerra’s camera captured an interview that I could not have conveyed if the editors gave me the entire “A” section and half of Sports. Print could not capture the amazing volume of tears that spilled down her face, or the cracking in her voice as she recalled Franklin’s last moments. Upon his diagnosis, doctors gave him six months to live, but he barely made it one month.

Weeks later, that same camera came along with us to Philadelphia, home of Rohm and Haas’s world headquarters and the attorney who took the villagers’ cases. It captured the crusading style of Aaron Freiwald, a former investigative reporter himself before entering law, as well as the measured tones of Rohm and Haas’s spokesman and the company’s counsel.

As we traveled down the back roads of eastern Pennsylvania, multimedia helped capture the curious tale of Spring House, a Rohm and Haas research campus where 15 or so employees, five of them in one hallway, have developed brain cancer. Moving pictures again told a thousand words as former corporate executive Tom Haag gave us a tour in his car, pointing out who died in which part of which building.

And while the interview of widow Joan Szerlik didn’t have the raw grief of Branham’s—it had been 14 years since Szerlik lost her husband, who worked at Spring House, to brain cancer—it caught how perplexed she was at the company’s conclusion that the 15 cases were coincidence.

The story’s true test came when Editor Dan McCaleb sat down at Guerra’s computer to watch the first video of the series, which featured Branham’s heart-wrenching tale. Through the corner of my eye, I noticed the boss tearing up a bit, which is no small feat if you ask any journalist. The verdict was in, although unspoken—the time and money spent on the project was more than worth it.

Digging Up Buried Information

But what kind of investigative work could a newspaper with the limited resources of the Northwest Herald hope to execute? I was an army of one writer—no bright-eyed college interns, no gofers, only me. Six stories averaging 100 inches, not counting sidebars, based on numerous interviews and tens of thousands of pages of data, requires the Melinda Mae approach. (Melinda Mae was the little girl in a Shel Silverstein poem who decided to eat a whale. She did it in 89 years, which I didn’t have.)

Melinda Mae did it one bite at a time. Likewise, all I could do was begin to pore over everything—one page, one question at a time. But doing so required a flurry of FOIA requests to local, state and federal agencies, as well as about $1,500 worth of legal dockets downloaded from the U.S. District Court where a class-action lawsuit on behalf of McCullom Lake residents had been filed.

This deliberative strategy paid dividends. The information I received showed, for starters, that the former owners of one of the factories knew about the pollution a decade before reporting it to environmental authorities. Private e-mails from the environmental consultants who mapped the water pollution showed they had serious concerns about the accuracy of their data.

For me, the bigger question was just how the McHenry County Department of Health had done its research to reach its conclusion that nothing was wrong, when it found that the defendant manufacturers were not responsible for these cancers. Just one month after the first lawsuits had been filed, county health officials had pronounced before worried village residents that local cancer rates were not above average and presented maps showing the contamination far from village wells. But the cancer data the county relied on were from years before nearly everyone involved in these lawsuits had gotten sick. More ominously, many of the maps that the county trotted out to calm the masses stated in small letters, “Provided by Rohm and Haas.”

Curious as to whether the county appointed a fox to guard a chicken coop on the taxpayer’s dime, I acquired every e-mail, document or cocktail napkin in which county officials referenced the brain cancers, as well as attorney Freiwald’s deposition of the county epidemiologist. What I found was the crowning achievement of our series, as our watchdog journalism enabled us to publish evidence of government failing the people.

The series revealed that, aside from relying on out-of-date data and maps provided by the defendant companies, the epidemiologist depended on college textbooks, class notes, and Web sites to hastily assemble the study. The study had no protocol, ignored accepted standards for researching disease, and its authors privately ran it by Rohm and Haas executives before showing it to the public.

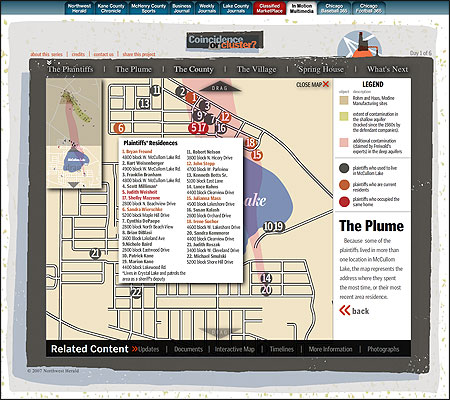

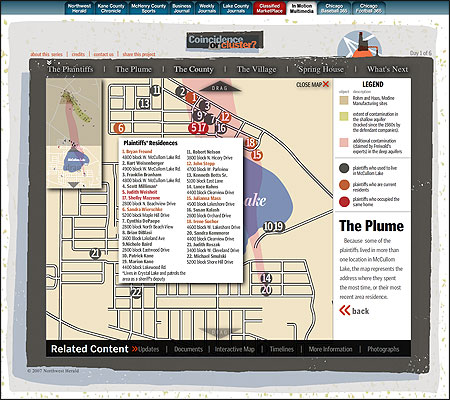

This interactive map gives users the ability to see where cancer patients lived in proximity to one another and to the factories and the alleged water contamination. Map courtesy of the Northwest Herald.

Public Reaction

The series, “Coincidence or Cluster?,” was published in December 2007. It has won at least a dozen awards for investigative and online journalism, but its ultimate accolade is one that Guerra and I strived for from the start—none of what we reported in the series has ever been proven wrong. Not one fact, not one statistic has ever been successfully disputed, though county officials tried—if by “tried” one means that they jumped up and down and screamed about the stories. In a meeting in which they planned to highlight “key facts” we chose to “downplay, spin or ignore,” their defense amounted to the fact that the whole mess was state government’s responsibility.

Our diligence did not end with the series. As with any good investigative effort, “Coincidence or Cluster?” shook other facts loose. For example, we learned that county officials downplayed some critical facts involving their own activity in regard to this public health issue; they obtained some of the bombshell memos in our series a year before it ran, but chose not to read them.

Following our series, one advisor to the county health board told its members, “People’s memories who read the newspapers are short. So maybe in about a year, nobody will remember this.”

Yet again, they were wrong. And the reason is because a small newspaper refused to believe it was too small to tackle such an ambitious project, not only in print, but also with video.

Kevin Craver, senior reporter at the Northwest Herald, got his start in journalism drawing comic strips for the Northern Star, his college newspaper. He and Danielle Guerra were named 2008 Journalists of the Year by Suburban Newspapers of America for their work on “Coincidence or Cluster?.” The series has won recognition from The Associated Press, the Illinois Press Association, the Chicago Headline Club, Washington Monthly, and the Chicago Journalists Association.

It’s a phrase I’d never uttered in seven years with the Northwest Herald, a small paper in McHenry County, Illinois, two of them as the newspaper’s senior reporter. In these trying times for newspapers, talking the editors of a 38,000-circulation daily into two plane tickets and two hotel rooms is worthy of a story in and of itself.

Sitting in the passenger seat on the sunny October 2007 day was Danielle Guerra, a 22-year-old videographer and Vanderbilt University graduate, whose persistence was one of the reasons for the trip. And ahead of us on I-10 was an interview that we both wanted and dreaded to conduct. Waiting in that Phoenix suburb was Joanne Branham, who lived much of her life in the small town of McCullom Lake, nestled in McHenry County, a county northwest of Chicago. She and her husband of 44 years, Franklin, had moved to Arizona after raising five children to spend their sunset years somewhere warm.

But that was not to be—Franklin died in 2004 of glioblastoma multiforme brain cancer, a deadly disease that afflicts slightly more than three people per 100,000. That wasn’t the main reason Danielle and I hopped on a plane. Months after Franklin’s diagnosis, two of his former next-door neighbors in McCullom Lake were diagnosed with brain cancer as well. All three families in April 2006 sued two manufacturers, Rohm and Haas and Modine Manufacturing, located a mile north of their homes in the neighboring village of Ringwood. For decades, consultants had tracked a plume of volatile organic chemicals in the groundwater from their operations.

After more than a year of covering the issue piecemeal, Guerra and I convinced our editors to let us pursue what turned into a six-part investigation full-time, also atypical for such a small-size newspaper. By the day of our trip, 22 current and former residents, all but four with brain and nerve cancer, had sued the companies.

One of my favorite proverbs from a book of sayings that my late father kept in his study was that age and treachery will always overcome youth and skill. But whoever came up with that bromide never examined what could happen if you merged the two—Guerra’s youth and skill and my age and treachery—toward a common goal. The two of us—and the Northwest Herald—banked our reputations on the answer.

In the multimedia presentation of this story, Joanne Branham expresses profound sadness about her husband’s death from a glioblastoma multiforme brain tumor that she and other families similarly affected believe was caused by industrial contaminants near their home in McCullom Lake, Illinois.

Moving Pictures

I had worked on stories with multimedia components before embarking on this series, but nothing this ambitious. Guerra and I agreed at the beginning that every story in the series would have accompanying video, and I attended almost every interview or shoot that she conducted. I quickly learned of multimedia’s potential—its raw power to reach out and grab viewers by the collar and not let them go.

Arizona’s climate had been good to Joanne Branham. She was healthier than many people half her age, and she had the energy to manage a restaurant, where patrons affectionately called her “Aunt Jo.” Guerra’s camera captured an interview that I could not have conveyed if the editors gave me the entire “A” section and half of Sports. Print could not capture the amazing volume of tears that spilled down her face, or the cracking in her voice as she recalled Franklin’s last moments. Upon his diagnosis, doctors gave him six months to live, but he barely made it one month.

Weeks later, that same camera came along with us to Philadelphia, home of Rohm and Haas’s world headquarters and the attorney who took the villagers’ cases. It captured the crusading style of Aaron Freiwald, a former investigative reporter himself before entering law, as well as the measured tones of Rohm and Haas’s spokesman and the company’s counsel.

As we traveled down the back roads of eastern Pennsylvania, multimedia helped capture the curious tale of Spring House, a Rohm and Haas research campus where 15 or so employees, five of them in one hallway, have developed brain cancer. Moving pictures again told a thousand words as former corporate executive Tom Haag gave us a tour in his car, pointing out who died in which part of which building.

And while the interview of widow Joan Szerlik didn’t have the raw grief of Branham’s—it had been 14 years since Szerlik lost her husband, who worked at Spring House, to brain cancer—it caught how perplexed she was at the company’s conclusion that the 15 cases were coincidence.

The story’s true test came when Editor Dan McCaleb sat down at Guerra’s computer to watch the first video of the series, which featured Branham’s heart-wrenching tale. Through the corner of my eye, I noticed the boss tearing up a bit, which is no small feat if you ask any journalist. The verdict was in, although unspoken—the time and money spent on the project was more than worth it.

Digging Up Buried Information

But what kind of investigative work could a newspaper with the limited resources of the Northwest Herald hope to execute? I was an army of one writer—no bright-eyed college interns, no gofers, only me. Six stories averaging 100 inches, not counting sidebars, based on numerous interviews and tens of thousands of pages of data, requires the Melinda Mae approach. (Melinda Mae was the little girl in a Shel Silverstein poem who decided to eat a whale. She did it in 89 years, which I didn’t have.)

Melinda Mae did it one bite at a time. Likewise, all I could do was begin to pore over everything—one page, one question at a time. But doing so required a flurry of FOIA requests to local, state and federal agencies, as well as about $1,500 worth of legal dockets downloaded from the U.S. District Court where a class-action lawsuit on behalf of McCullom Lake residents had been filed.

This deliberative strategy paid dividends. The information I received showed, for starters, that the former owners of one of the factories knew about the pollution a decade before reporting it to environmental authorities. Private e-mails from the environmental consultants who mapped the water pollution showed they had serious concerns about the accuracy of their data.

For me, the bigger question was just how the McHenry County Department of Health had done its research to reach its conclusion that nothing was wrong, when it found that the defendant manufacturers were not responsible for these cancers. Just one month after the first lawsuits had been filed, county health officials had pronounced before worried village residents that local cancer rates were not above average and presented maps showing the contamination far from village wells. But the cancer data the county relied on were from years before nearly everyone involved in these lawsuits had gotten sick. More ominously, many of the maps that the county trotted out to calm the masses stated in small letters, “Provided by Rohm and Haas.”

Curious as to whether the county appointed a fox to guard a chicken coop on the taxpayer’s dime, I acquired every e-mail, document or cocktail napkin in which county officials referenced the brain cancers, as well as attorney Freiwald’s deposition of the county epidemiologist. What I found was the crowning achievement of our series, as our watchdog journalism enabled us to publish evidence of government failing the people.

The series revealed that, aside from relying on out-of-date data and maps provided by the defendant companies, the epidemiologist depended on college textbooks, class notes, and Web sites to hastily assemble the study. The study had no protocol, ignored accepted standards for researching disease, and its authors privately ran it by Rohm and Haas executives before showing it to the public.

This interactive map gives users the ability to see where cancer patients lived in proximity to one another and to the factories and the alleged water contamination. Map courtesy of the Northwest Herald.

Public Reaction

The series, “Coincidence or Cluster?,” was published in December 2007. It has won at least a dozen awards for investigative and online journalism, but its ultimate accolade is one that Guerra and I strived for from the start—none of what we reported in the series has ever been proven wrong. Not one fact, not one statistic has ever been successfully disputed, though county officials tried—if by “tried” one means that they jumped up and down and screamed about the stories. In a meeting in which they planned to highlight “key facts” we chose to “downplay, spin or ignore,” their defense amounted to the fact that the whole mess was state government’s responsibility.

Our diligence did not end with the series. As with any good investigative effort, “Coincidence or Cluster?” shook other facts loose. For example, we learned that county officials downplayed some critical facts involving their own activity in regard to this public health issue; they obtained some of the bombshell memos in our series a year before it ran, but chose not to read them.

Following our series, one advisor to the county health board told its members, “People’s memories who read the newspapers are short. So maybe in about a year, nobody will remember this.”

Yet again, they were wrong. And the reason is because a small newspaper refused to believe it was too small to tackle such an ambitious project, not only in print, but also with video.

Kevin Craver, senior reporter at the Northwest Herald, got his start in journalism drawing comic strips for the Northern Star, his college newspaper. He and Danielle Guerra were named 2008 Journalists of the Year by Suburban Newspapers of America for their work on “Coincidence or Cluster?.” The series has won recognition from The Associated Press, the Illinois Press Association, the Chicago Headline Club, Washington Monthly, and the Chicago Journalists Association.