“I, and scores of my fellow American foreign correspondents, had been tracking stories about al-Qaeda and its allies for more than a decade. But we rarely reported what we knew on network television news—because, much of the time, our bosses didn’t consider such developments newsworthy.” —Tom Fenton

In his sobering new book, Tom Fenton, long overseas for CBS News, has a new twist on an honored tradition, memoir writing by foreign correspondents. Instead of reliving what he has seen and explaining what it all meant, his central theme is what might have been—if only his bosses had the wisdom to care enough about foreign news, if rating- conscious news consultants didn’t have so much influence, if the Federal Communications Commission had not dropped the requirement for public service broadcasting, and if journalists themselves did not fear offending one special interest group or another.

Instead of celebrating foreign reporting in the time-honored way, he eulogizes it. “On some nights prior to 9/11,” Fenton writes, “the network news shows featured no foreign news at all.”

Fenton’s book is doing just what he professes to want to do—stir up debate on the subject and possibly provoke change. “I would like to give back something to my profession—the sense of responsibility to the public that we seem to have forgotten,” he writes early on in the book.

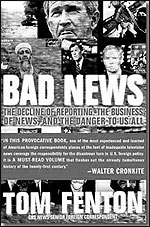

Already I have praised Fenton’s hardhitting book in a review I wrote for The (Cleveland) Plain Dealer. In “Bad News,” Fenton powerfully and usefully dramatizes an urgent problem: Will Americans be equipped with the facts they need to deal with an increasingly interdependent and hostile world? In this more reflective piece, however, it might be worth pondering one aspect of Fenton’s argument that seems not to be getting the attention it deserves: the glorious past to which he alludes.

Changes in Foreign Correspondence

The true golden age of foreign correspondence was not the cold war years, as Fenton and others who did their work then often claim. Rather it was the time between World Wars I and II, also a period when memoir writing by foreign correspondents crested. The most perceptive correspondent of the time was Vincent Sheean, described by a colleague as “reporter, writer, philosopher and prototype of the dashing, almost legendary foreign correspondents of the old ‘I was right there on the spot’ school.” Sheean’s “Personal History,” published in 1935, begat a number of other best selling memoirs by foreign correspondents.

Those memoirs, which were really extended reports of what correspondents were seeing on the ground, warned of the coming global conflict. They also had remarkable literary quality. “To me the most impressive feature of the story,” said critic Malcolm Cowley of “Personal History,” “is that besides being an extraordinarily interesting personal document, it is also, by strict standards, a work of art.”

This golden age did not come about simply because Sheean, Dorothy Thompson, Paul Scott Mowrer, Negley Farson, John Gunther, Edgar Snow—the list goes on and on—were blessed with talent. Every age has talent. The difference was the conditions in which those correspondents worked—conditions that do not exist today. Here are a few examples of what was and is no longer:

- The Saturday Evening Post, Collier’s, Look, Liberty, Life and many other magazines fielded their own overseas reporters and made extensive use of freelancers like Sheean. Likewise, the North American News Alliance and the Consolidated Press, to name just two specialized news services at the time, flourished. Those media, which paid correspondents well and let them write at length, are gone. Likewise, the newspaper that pioneered the concept of a comprehensive supplementary foreign news service, The Chicago Daily News, is gone, as are our other newspapers that fielded superb corps of correspondents.

- Technology had not yet reached the point at which correspondents were in touch with the home office all the time. On a long leash, correspondents enjoyed a high degree of independence to roam and take their time on stories.

- The relative cost of living abroad was significantly cheaper than it is today. A young reporter who wandered into Beijing in the mid-1930’s lived in “Oriental luxury for as little as $60 a month.” In the countryside, it was said he needed only half that much. Even adjusting for inflation, there are few places in today’s homogenized world where one can live decently on little.

- In addition to being liberated by the strong dollar, correspondents—like much of the rest of America—were not yet fully acculturated to the benefits of corporate life. In 1940, some sort of health plan covered less than 10 percent of Americans. Fifty years later, with the costs of health care escalating, it was just the opposite, and most people acquired that insurance through an employer.

- Finally, Americans were well liked, and this gave correspondents an advantage in seeking news. One of the greatest scoops ever by a foreign correspondent was Edgar Snow’s “Red Star Over China,” which revealed in the mid-1930’s that the Chinese Communists were not mere red bandits, but a viable political force. It came about because he was allowed to visit the Communist-held areas. It was unimaginable the Communists would have invited a French, British or German journalist to check them out. Leaving aside all the questions about whether the United States should still be admired today, we are now viewed the way those imperial nations were half a century ago, as an aggressor.

Even in that golden age, readership interest was problematic. Foreign reporting, Sheean complained, “was substantially useless because the forces of public opinion and of official power paid so little attention.” Instead of preemptive action abroad, the United States passed neutrality laws.

Foreign Reporting Falters

Fenton suggests we have no data telling us that the public doesn’t care about foreign news. Yet later on, he breezily acknowledges that “The instant an anchor utters the word Azerbaijan or Indonesia, he’s fighting against a ticking meter of declining viewers.”

For an obvious reason, the amount of foreign reporting rises when the United States is involved in wars abroad. Such conflicts are, after all, local stories: Our neighbors’ son or daughter is abroad fighting. But absent U.S. troop involvement in a war, foreign affairs typically occupy a small share of the news hole in most dailies and broadcast reports, as indeed was the case in these earlier interwar years.

In the ups and downs of foreign reporting, Fenton is correct that broadcast media have faltered much more than print. Broadcast news hit its stride at precisely the moment when foreign news became urgent—the outbreak of hostiles in Europe in the late 1930’s. Among the radio pioneers were, in addition to the iconic Edward R. Murrow, William Shirer, Eric Sevareid, and Sheean, to name only a few of the print journalists who moved permanently or temporarily to the airwaves. Their expertise at such a poignant time helped radio achieve an extraordinarily high standard.

The reasons broadcast has fallen so far since is rooted in economics. Unlike newspaper correspondents, Fenton notes, broadcast reporters have agents who secure large salaries for them. In the absence of compelling public interest in foreign news, it simply doesn’t pay to put those expensive reporters and crews in the field, especially when the broadcast audiences that advertisers want to reach most are ones that tend to care the least about foreign news. Don Hewitt, the long-time producer of “60 Minutes,” ABC News anchor Peter Jennings, and former CBS News anchor Dan Rather told Fenton that at one time or another each had offered to forego some of his salary so more money could be spread to other parts of the news operation. “That’s not the way it works,” Rather was told.

This brief look back into journalism history offers no solace for foreign correspondence practiced the traditional way. The only hope for its survival lies in thinking about foreign news differently. And those who really need access to foreign news continue to find ways of getting it, no matter what traditional establishment mass media do. Bloomberg News, for instance, still has scores of reporters abroad; to get news from them, one simply has to be willing to pay a premium. And there is no doubt that the Internet has improved the flow of foreign news for savvy users who rely not only on U.S. publications, but seek out news and commentary from news organizations with local reporters on the ground or from Webloggers.

If old-line mass media are to play a role, their leadership must think in nontraditional ways. Fenton notes that many point to public radio as an alternative model. Public radio is the only U.S. radio news outlet that provides in-depth news, either foreign or domestic. It relies on a mix of subscriber contributions and foundation support, government and corporate funding to support its costly dedication to providing its more comprehensive news programming. This approach needs much more discussion than it is likely to get.

Fenton is less creative in his treatment of news managers, whom he blames for not supporting foreign news more than they do. He dislikes the technique of news packaging in which video shot in Tanzania, for example, is combined with a voiceover report done by a correspondent in London and fashioned into a story for broadcast. Such packaging might not be optimum. But given the economics now at work, more thinking needs to be done about how to use such techniques effectively instead of fruitlessly arguing for a return to days of yore. I believe those executives deserve praise rather than opprobrium for attempting to find solutions to problems shareholders don’t care much about. Similarly, we need to give more credence to the creative approaches newspapers are trying. They are getting much better at using specialized home-based staff to undertake stories with a foreign angle. The Dallas Morning News, for example, sent two special project reporters abroad to track the whereabouts of Catholic priests who were convicted of crimes and fled the country before sentencing. The Chicago Tribune sent a music reporter to do stories in Panama and Cuba. Newspapers are also doing a better, if uneven, job of exploring trade relationships and other links between their communities and those who live abroad.

I wish the golden age of the interwar years still existed. Journalists like Sheean inspired me to go abroad as a freelance correspondent when I was young. But we live in a very different world, and we have to make the best of it if the public is to be equipped to deal with the global challenges that face them. Somebody has to “make the story,” Sheean said of the need for foreign news reporting, “or there is not going to be one.”

John Maxwell Hamilton, dean of the Manship School of Mass Communication, Louisiana State University and a long-time journalist, is at work on a history of foreign news.