As a reporter in the 1960’s and 1970’s, Philip Meyer pioneered the use of social-science methods in daily newspaper journalism. Using extensive polling, counting and statistical techniques, he tunneled deeply into issues of crime, poverty and education. One of his early stories, which appeared in the Detroit Free Press in 1967, analyzed the backgrounds and attitudes of the city’s rioters. His stories challenged conventional wisdom and demonstrated the degree of alienation among the city’s young black residents. In 1973 he published his influential book, “Precision Journalism,” which opened the door of quantitative methods to a generation of journalists who have investigated innumerable local and national issues from police corruption to airline safety.

Now, 50 years after entering the newspaper business as a reporter and with fears for its future, Meyer has written a new book, “The Vanishing Newspaper: Saving Journalism in the Information Age.” In it, he turns his prodigious skills of analysis back on the newspaper industry itself. “Journalism is in trouble,” he says in the opening. “This book is an attempt to save it.”

The mission he initially set for himself was to show that money spent on putting out a good newspaper could be justified on the basis of achieving a stronger market position and bigger profits. At first glance this hardly seems a controversial idea. It’s difficult to imagine other manufacturers arguing over whether consumers would respond to better-made cars, clothes or refrigerators. Isn’t the pursuit of quality how Japan came to dominate the auto industry?

In the newspaper industry, though, especially in the past two decades, the concept of increasing the investment in editorial quality, or even moderating the impulse to cut newsroom budgets, has become a battlefield. On one side: editors with a blind faith in the power of potent journalism to win readers and improve society. On the other side: business-oriented managers with an unbending commitment to controlling costs and hitting the numbers that reward investors.

University of Missouri press recently released an updated second edition of Philip Meyer's "The Vanishing Newspaper: Saving Journalism in the Information Age." The new edition applies the original premise from 2004, that newspapers' main product is influence, to the events that have transpired over the last 5 years.

While the marketplace is typically left to settle these disputes, the practice of journalism—like public health and education and unlike the manufacturing of automobiles—has implications for the welfare of society that make it a matter of public concern. The failure of newspapers would have a more damaging effect on our nation than, say, the loss of the shoe industry or the flight of textiles to China.

In a period of declining circulation and public trust, it is a commentary on our times that budgets have become the key point of contact between editors and publishers (or corporate CEO’s). Most other issues—winning new readers, leading editorial crusades, or developing new editions or services—have been subordinated to secondary status as endless hours are spent on head count, evaluating the costs of overlapping wire services, or trimming freelance expenditures. As anyone who has been close to these matters knows, editors and their budgets have not fared well for quite some time. In fact, because the momentum toward leaner staffs and smaller budgets is so well established, and even accepted, the entire topic has become a little tired. It has come to feel like a settled issue, not unlike the annexation of Texas. Many of the editors who fought against the trend have departed with severance packages or escaped to academia, taking with them years of experience and idealism and reservoirs of talent and energy. Most who remain have reconciled themselves to the new order. In the meantime, newspaper circulation continues to decline, and swaths of the public are uninformed about important world and national events.

The Value of Quality Journalism

It is into this state of affairs that Meyer steps. So in the context of what has happened in the nation’s newsrooms and where journalism seems to be heading, his book amounts to a kind of “Hail Mary” pass in the final minutes of the game. To demonstrate empirically, and in quantitative terms, that quality journalism pays would cause an awful lot of beleaguered journalists to stand and cheer. Meyer is an estimable journalist and scholar who occupies the Knight Chair in Journalism at the University of North Carolina. He had a long career with Knight Ridder, both as a journalist and corporate executive, before entering academia, and his research has been widely published in scholarly journals and trade magazines. He is particularly well prepared to argue the case for an investment in journalism.

In the end, Meyer’s book turns out to be less an argument than a prayer. Its most persuasive chapters, unencumbered by numbers, are a recounting of the industry’s transition from private to public ownership and an elegy to a gallery of leaders from the past—philosopher-kings, he calls them—who acted, in large part, on the idea that good journalism was important to the lives of their communities. The nostalgia is there, though Meyer tries mightily to resist it.

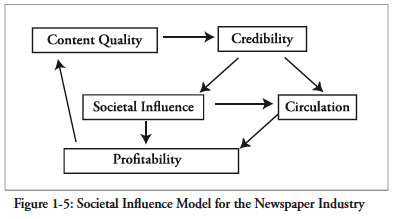

The frame for Meyer’s brief is what he calls the “Influence Model,” a way of seeing and managing the newspaper business that he traces back to Hal Jurgensmeyer, a former (and now deceased) vice president at Knight Ridder. At the time of his meeting with Jurgensmeyer in 1978, Meyer had just left his job as a reporter to become Knight Ridder’s first director of news research. Jurgensmeyer, a business-side executive, gave Meyer a briefing and sketched out his view of the business. Meyer explains: “A newspaper, in the Jurgensmeyer model, produces two kinds of influence: societal influence, which is not for sale, and commercial influence, or influence on the consumer’s decision to buy, which is for sale. The beauty of this model is that it provides economic justification for excellence in journalism.” It’s an approach that strikes the perfect pitch for an organization such as Knight Ridder: a reasonable, cool, pragmatic and noneccentric statement of mission. It’s a mission that wears a suit and sits comfortably at meetings of the board of directors.

(Note of disclosure: Like Meyer, I’m a former Knight Ridder employee, and I continue to own a small amount of its stock. Soon it will be sold to pay for my son’s final semester of college.)

The Jurgensmeyer model is a tidy formulation, but one of the problems with it (leaving out the entire matter of the junk-mail industry’s ability to achieve phenomenal financial success without a shred of social influence) is that it lacked a quantitative underpinning. As stated in the 1970’s, it was an elegant and appealing concept on which the gentlemen (and occasional gentlewomen) of Knight Ridder could agree. How much influence was necessary to sell advertising, and how much should the organization be willing to spend to maintain or extend it? These were matters that were left uncalculated, and they would not become consequential for another decade when the financial rules of the newspaper business began to stiffen. By then, most editors were already on the defensive.

Much of “The Vanishing Newspaper” is an attempt to provide the numbers to support the logic of Jurgensmeyer’s model. Meyer’s approach to the data deficit is to establish correlations between the markers of journalistic quality and surrogates of business success, especially circulation performance. One of the marvels of Meyer’s creative and analytical genius is his ability to assemble these surrogates. One of the more interesting and useful is what he calls “penetration robustness.” It is essentially an index of a newspaper’s ability to maintain its penetration of households against the forces that are eroding it. Since circulation penetration, especially in the newspaper’s home county, is as good a sign of a franchise’s health as one is likely to find, it is a credible stand-in for profitability over the long-term.

Armed with these markers and surrogates, there’s no end to what Meyer finds to measure. He finds relationships between credibility and circulation, credibility and advertising rates, readability and circulation, staff size and circulation, and even positive copyeditor attitudes and circulation. Most of this cannot be read without concluding that this book is also a wise old professor’s hymn to the very process of measuring and analyzing data. Consider this:

“When we use regression methods, we are trying to explain variance around the mean of the dependent variable. We do it by looking for covariance—the degree to which two measured things vary together. If we know a lot about these variables and the situations in which we find them, we might even start to make some assumptions about causation. But correlation is not by itself enough to prove cause and effect. No statistical procedure can do that. In the end, we are left with judgment based on our observations, knowledge and experience with the real world. We still have stuff to argue about. But with the discipline of statistics, as Robert P. Abelson has said, it is ‘principled argument.’”

In one astonishing section, a digression into the alleged benefits of civic journalism, Meyer shows that newspapers with strong civic journalism reputations enjoy long-standing community-focused organizational cultures. How did he establish that these nascent civic-journalism impulses existed in the newspapers’ pasts? He created two “dictionaries,” one of words that show a business focus (“profit,” “efficiencies,” “cash,” etc.) and another of words that show a community focus (“awards,” “integrity,” “quality,” etc). Then he collected 179 annual reports going back to 1970 from 19 publicly traded companies. He and his graduate students ran the CEOs’ messages to shareholders from the reports through an optical scanner and used a computer program to count the word hits against the two “dictionaries.” The companies that scored high on community focus, it turns out, are the same ones that have been pursuing civic journalism agendas in recent years. While this effort could be seen as almost medieval in its fixation with counting, it does make an important point: There are few quick fixes when it comes to changing a newspaper’s culture. A company’s history predicts its future.

Brick by brick, number by number, Meyer builds his case for quality. In his demonstration of the link between credibility and circulation, he assembles a list of 20 counties in which he has numbers on circulation robustness (drawn from Audit Bureau of Circulation reports) and credibility scores for the counties’ dominant newspapers. He draws the credibility numbers from a regularly recurring survey by the Knight Foundation of former Knight newspapers. The survey question asks respondents to rate their daily newspaper: “Would you say you believe almost all of what it says, most of it what it says, only some, or almost nothing of what it says?” For the circulation numbers, he uses his “circulation robustness” index, a measure of the paper’s ability to hold penetration against a baseline. A graph that plots the two variables shows a kissing relationship between quality and circulation: “The slope of a straight line defining that relationship is 0.2 percent, meaning that annual circulation robustness—the ability of a county’s newspapers to hold their circulation in the face of all the pressures trying to degrade it—increases on average by two-tenths of one percentage point for each one percent increase in credibility.”

The exercise yielded a second insight: Credibility scores run higher in smaller communities. By working the numbers, Meyer demonstrates that credibility, not market size, stands as the key variable in predicting circulation robustness. This suggests that newspapers in large markets would benefit from strategies that allow them to break their markets into smaller pieces, thereby boosting the credibility that would give them a lever to raise circulation robustness. Zoning is one obvious strategy.

Narrating Newspapers’ Economic Journey

While Meyer’s findings are persuasive, they fall short of definitive proof. There are three problems: His work draws almost entirely on numbers from the Knight surveys of former Knight newspapers, which are not necessarily a broad, diverse or representative sample; the research excludes an analysis of the nation’s largest and most important newspapers, and finally the research shows only correlations between quality measures and business success, it does not show cause-and-effect linkages. Successful newspapers, for example, tend to have larger news staffs. In other words, the two variables are correlated. But what came first, business success or the larger staff? Which is the cause and which is the effect? To oversimplify, this is a little like going to a party and finding that everyone is well dressed and prosperous. One might ask: Are the guests prosperous because they are well dressed, or well dressed because they are prosperous?

Meyer readily admits this problem. “At the outset, I had hoped to produce evidence that a given dollar investment in news quality would yield a predictable dollar return that would more than justify the outlay. That might be possible, and the evidence in this book provides some support for the idea, but at nowhere near the level of precision that would excite an investor.”

Acknowledging the limits of his ability to supply the data to transform the Jurgensmeyer model from concept to equation, Meyer uses “The Vanishing Newspaper” to summarize the story of newspaper economics of the last three decades and put the narrative in a larger context. Here the book begins to shine a more useful light on the current malaise in the business of journalism. It also offers a hopeful if familiar solution: the reinvention of the business of journalism, based on the Jurgensmeyer model, on the Internet.

For decades, Meyer recounts, newspapers were a “tollgate” between retailers and consumers, and they enjoyed a long period of easy money. A cold wind began to blow with competition from new technologies (TV and cheaper offset printing, for example) and declines in readership. Despite these trends, newspaper executives maintained and even increased their historically high profit margins by raising advertising rates. Even though newspapers were losing penetration, they maintained local dominance, which allowed them to squeeze their advertisers. From 1975 to 1990, newspaper ad rates rose 253 percent. In the same period, the Consumer Price Index rose 141 percent. At about the same time, newspaper companies were enjoying big savings that came from their investment in new printing technologies. The money rolled in. There was joy in Mudville.

Clearly, neither of these sources of earnings—steadily rising but unchallenged ad rates and backshop savings—was sustainable in the long run, and the vice soon began to close. In this period, newspaper companies also were moving from private to public ownership, and they were coming to learn that one of the costs of turning to equity markets for capital was the outward flow of power to institutional investors and analysts—to new owners. An important shift would eventually occur. Where the psychic reward of owning a newspaper once had counted as a return, even if it didn’t show up on the income statement, the measure of success now had become strictly financial. If you think of running a newspaper as a board game, it went from being Chutes and Ladders to Monopoly in a hurry.

As managers looked for ways to improve earnings in this tougher-money environment, they turned increasingly to cost cutting. While a dollar added to operating revenues from investment in a new advertising initiative might yield 10-15 cents to net income, every cent of a dollar eliminated from the news department dropped straight to the bottom line. It was the bottom line—reported every 90 days as quarterly earnings—which Wall Street and the new owners of newspapers obsessively watched. At first, the reductions to news budgets came from higher rates of employee attrition as jobs were left “dark.” Layoffs soon followed. News bureaus were closed, copy desks thinned, Sunday magazines eliminated, and news holes trimmed. The capacity to cover news was shrinking.

Meyer sets these trends against larger forces operating in the society. He cites the research of Rakesh Khurana of the Harvard Business School: In 1950, large investors such as pension and mutual funds owned 10 percent of U.S. corporate equities. By the turn of the century, 60 percent of the ownership of corporate equities was in their hands. Ownership through the U.S. economy, Khurana found, had shifted from “family and friends of the founders” to institutional investors. Managers at newspaper companies were not alone in feeling the pressures to produce steadily improving earnings for Wall Street.

The pressures, while beneficial to investors, at least in the short-term, were potentially damaging to employees and consumers. Meyer cites the work of Jane Cote of Washington State University, who argues that financial pressures have damaged professional values across a range of industries. Meyer mentions accounting (the Enron debacle) and medicine (doctors selling their practices to health-care corporations) as professions whose codes of practices face potential distortions arising out of efforts to meet outsized financial demands. The biggest potential threat inherent in Meyer’s book, though, is the eventual demise of newspapers altogether.

Future Strategies

Courageously, Meyer enters the fray on the question of what constitutes a reasonable financial return for an industry whose product quality is consequential to the functioning of the republic. It seems to me, though, he backs out of the discussion early and without a sufficiently rigorous assessment of the current picture. The financial returns remain high and the reinvestment insufficient. What’s the reason?

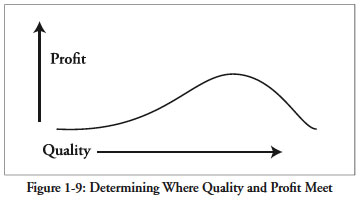

Corporate managers, Meyer writes, face a dilemma. To make his point, he employs the analogy of a goose that lays golden eggs. His explanation goes like this: Today’s newspaper owners (and investors) have made investments based on a goose they expect to lay a golden egg every day. Those golden eggs come in the form of profit margins in the range of 20 to 40 percent. These are the margins necessary to achieve their expected returns on investment. A goose that lays fewer golden eggs, say margins of 10 percent, is a bird worth owning. But it’s not the goose in which they have sunk their investment. So CEO’s are stuck with managing for high margins. The culprit is return on investment, Meyer asserts, and managers are trapped by the numbers.

Now there are a number of ways of responding to this explanation. First is to look at return on investment, which is the term that Meyer employs or, more specifically, to look at return on equity (ROE), which measures the return earned by common stockholders (owners). Some industries make a higher return on equity than newspaper companies, some make lower. For example, Reuters Fundamentals reports these five-year average for some other industries: autos, 18.84; life insurance, 11.08; retail grocery, 17.65; water utilities, 10.21. Historically, returns on common equity for American corporations run between 10-13 percent, though they have been running a good deal higher in recent years. The difference among industries tends to come down to the amount of risk an investor is taking on. Newspapers are not a risky business. Can you recall a dominant newspaper in a community failing? So one would expect returns on the lower end of the spectrum. Gannett’s average ROE over five years has been 18.16, according to Reuters Fundamentals. Other newspaper companies: Knight Ridder, 17.47; Tribune, 17.38; Lee Enterprises, 12.18. For the industry, according to Reuters Fundamentals, the average ROE is 16.81. For S&P 500 corporations, the five-year average is 19.02

A second, and I would suggest better, way of looking at the situation is to begin with a consideration of stock price. Investors place a value on a company when they buy its stock. The current value of stock in a company is based on the expectations of earnings in the future. In other words, investors look forward at earnings rather than back at investment when deciding how much to pay for a share of stock. So, the expected profits and returns are already built into the stock price. Any strategy that reduces those expected returns would lead investors to sell their shares. The value of the stock would fall, probably rapidly. One result of a sharp reduction in stock price would be that the people who hold lots of stock would experience a painful reduction in personal wealth. Another result would be the ability of a new investor to gain control of the company by picking up a big chunk of the lower-priced stock. A new owner might change management and strategy. These are powerful motivations for management to stay on the current path.

It’s worth asking, then, to what extent is the situation a numbers trap or, rather, the stubborn (though understandable) unwillingness of CEO’s to set in motion events that would sweep away some piece of stockholder wealth and result, possibly, in an unfriendly takeover?

Meyer’s argument is to reverse the existing dominant strategy: to reinvest in news coverage, increase influence, and achieve better business results. The problem, he says, is that newspapers face an additional problem, yet more competition in the form of a “disruptive technology” that may subsume, or seriously harm, its business.

So, he says, the stark choice newspapers face is this:

Take the money by maintaining high margins and not reinvesting. This is a strict liquidation strategy.

Or manage the decline to maintain quality but invest profits in substitute technologies, especially the Internet. Meyer sees some evidence of the former, but advocates the latter and falls back on Jurgensmeyer’s model—a framework, he says, that will work in the future as it has in the past.

A charismatic or committed CEO, who could pitch lower returns to investors as a way to secure the franchise and generate future returns, might be able to maintain investor loyalty as investment is directed to good journalism. In fact, it’s the way that has been charted for the flagship papers by leaders of those public newspaper companies that remain within the control of families such as the Sulzbergers and the Grahams. There are probably many more publishers who would argue for more investment, but investment in non-news areas such as circulation or advertising infrastructure as ways to keep the patient healthy.

In looking ahead, Meyer cites the seminal article “Marketing Myopia” by Theodore Levitt, which encouraged managers to see beyond their products and equipment into the essence of their businesses. His resonant example was the railroad industry. Railroad owners should have seen that their business was transportation and that self-knowledge, the argument goes, would have helped them make the transition to a new world in which railroads were less and less relevant. Because the business of newspapers is influence, Meyer asserts, executives need to maintain high levels of credibility in their brands even as they evolve into new platforms for exercising and selling their influence.

Meyer also quotes the work of Herbert Simon, who noted that in an information economy such as ours the scarce resource is attention. Newspapers aren’t just competing with newspapers or even just other forms of journalism and advertising. The competition includes video games and anything that occupies eyeballs. One way to capture attention is to become a trusted provider. Trust becomes the door that leads to influence and, eventually, through the alchemy of the right business model, profit in a new medium, possibly the online delivery of journalism. The journalism of the future may be a variation of its current form or some new form altogether.

The essential problem with Meyer’s argument, and why the issue remains a matter of open debate, is that journalism is more than a business, and the strongest arguments for quality combine economics and ethics. Of course Meyer knows this, but he keeps his sentiments on a leash. The ethical or social-benefits arguments don’t work with investors. The challenge Meyer has set for himself is to find a solution to the decline of journalism within the rules practiced by today’s publicly traded corporations.

Occasionally Meyer lets his idealism off its leash. There are sections of “The Vanishing Newspaper” that achieve a kind of lyricism that spring from his personal recollections of what he calls “the Golden Age,” when powerful public-spirited proprietors (“philosopher kings”) owned newspapers.

It’s impossible not to hear the thrill in Meyer’s voice as he recalls John Knight’s motto, “Get the truth and print it,” or when he quotes Jim McClatchy describing the mission of his family’s newspapers. To stand up to “the exploiters—the financial, business and political powers whose goal was to deny the ordinary family their dreams and needs in order in order to divert to themselves a disproportionate share of the wealth of the country.” These men were counting the social benefits—what economists would call the “externalities”— as returns. Ego probably played a part as well.

In one of the most profound passages of the book, which goes to the nub of the problem with the current model in which journalism is being practiced, Meyer writes:

“The reason newspapers were as good as they were in the Golden Age was not because of the wall between church and state. It was because the decision-making needed to resolve the profit-service conflict was made by a public-spirited individual who had control of both sides of the wall and who was rich and confident enough to do what he or she pleased.”

For those of us who have had an opportunity to work under the old system and the new, we know the personal satisfaction and public benefit of an enlightened and public-spirited owner. We also know that private ownership is not necessarily a panacea. Lots of private owners managed their papers for personal gain; public service was an afterthought. It came down, as so many things do in life and business, to character. We also know that the old system is not returning for most newspapers. As Meyer rightly and wisely notes, “The world has moved on.” But the need for good journalism remains.

And that takes us back to the argument that an investment in quality must make business sense. Otherwise it is not likely to occur in most organizations. Those of us who have seen the benefits of good journalism believe the quality argument in our guts. Meyer wants to give us the quantitative link. That’s the wall that he keeps trying to scale. Bless him for throwing himself against it so stubbornly.

Lou Ureneck, a 1995 Nieman Fellow, is professor of business and economics journalism at Boston University and the journalism department’s director of graduate studies.