My photographic journey into the lives of black youth in Baltimore began in an accidental way. The newspaper I worked for sent me to photograph a young woman for a column called “Candid Closet,” and she was supposed to represent one of the most fashion conscious people in the city. Known for her Sunday-best dress hats, she had inherited part ownership of her family’s successful funeral business in Baltimore.

As I was photographing her, I was having a hard time finding a good location with the kind of light I wanted. I backed into a large room, filled with daylight, turned around, and found myself staring into the face of a dead 13-year-old boy. He was dressed in an off-white suit and his tiny frame squeezed tightly into a narrow casket. He seemed ready to open his eyes at any moment.

Sweat was rolling down my arm and, after a long moment of silence, this woman said, “That’s nothing new. It’s happening all the time.” She began to tell me about all the young people being killed and killing each other. She said that youngsters in the city had grown accustomed to death, to seeing its face up close, to visiting their friends in funeral homes, and talking about it as they might a social outing. It was one more party to dress up for, another occasion to wear black.

Her words shook me. It was after this experience that I began what was to become a five-year photographic journey into black neighborhoods of Baltimore, Chicago and New Orleans trying to understand and convey through images what was happening to their young.

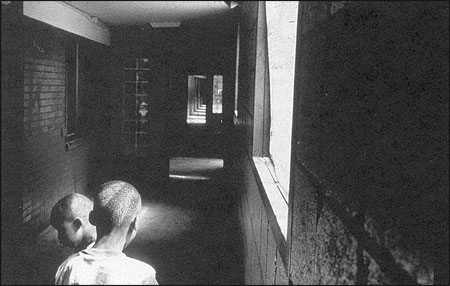

Robert Taylor Homes projects in Chicago. Photo by Andre Lambertson.©

These youngsters endure the harsh realities of deprivation and racism. Many of these children attempt to shield themselves from an environment they find profoundly threatening. Beneath their stony exteriors there is trauma that outsiders rarely know. I was familiar with the work of some photographers who had tried to portray the poverty and despair within some black communities, but I didn’t feel the photographs conveyed insights deeper than the obvious circumstances. I wanted my work to help me and others understand why these neighborhoods continued to devour their children, how children who lived there saw themselves, and where they found hope. Most deeply, I wondered how I could help. After all, I was drawn to photojournalism because I felt it was a tool I could use to bring about positive change in people’s lives.

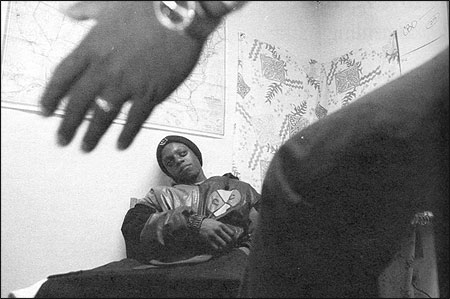

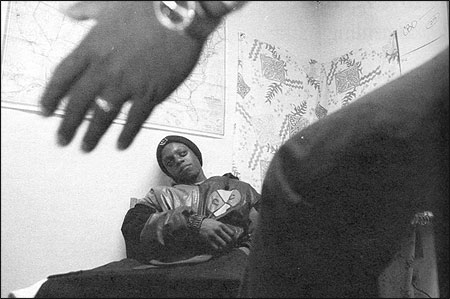

With a counselor from Gang Peace, a young man talks about available jobs.

I think that the best journalist is seldom subjective. Any journalist with enough curiosity and heart can tell any story if he asks the right questions of himself. To tell the best stories, he relies on his heart. He uses what he knows, often his own experiences, to get inside a story, to find its walls and penetrate them. Being black and adopted, I wondered how I would have fared in one of these communities. A loving and strong parent had helped me to find my path and stay out of harm’s way, and perhaps this made me want to tell these stories about children who didn’t have someone to do this for them. The biggest question I asked myself as I documented these children’s lives was why people don’t care more about why they are dying so young.

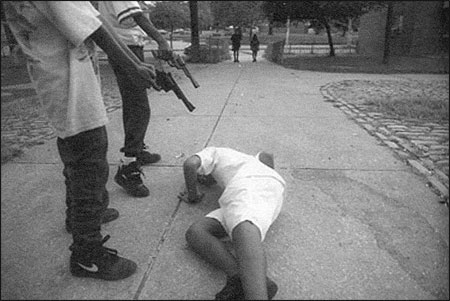

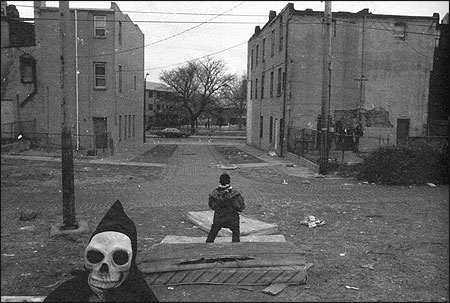

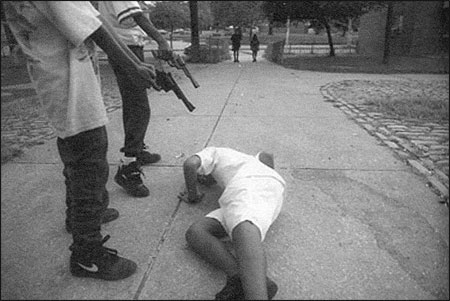

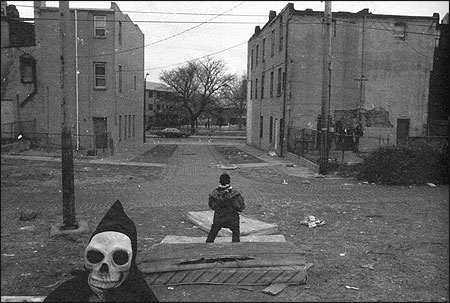

Boys playing cops and robbers at LexingtonTerrace, West Baltimore.

When I mentioned this idea of photographing these children and their communities, my editors back at the newspaper told me simply ‘Kids killing kids is nothing new. The story has been done.’ But I feel that it is the job of journalists to tell stories again and again in new and creative ways. By bringing a deeper, more complex way of examining the issues of juvenile violence, I wanted to shed light on the complicated conditions and issues that embraced these children. No one was born a killer. What happened along the way to make them do this? And I wondered how the mainstream press would have reacted if these children were white. Would this be considered an epidemic? Of course, this was before Columbine happened.

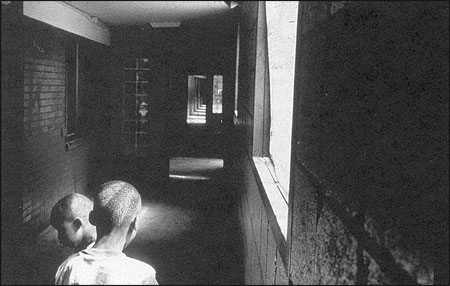

Cabrini-Green projects in Chicago.

My burning desire to be a photojournalist was fueled largely by my desire to be seen and heard and to give voice to those who aren’t heard. The apathy toward this story that I heard from my editors pushed me harder to do it. I wanted to show dimensions of these youngsters’ lives that would portray them in more sensitive ways. I felt the mainstream press often demonizes these youth.

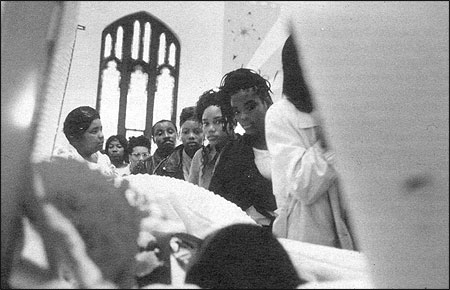

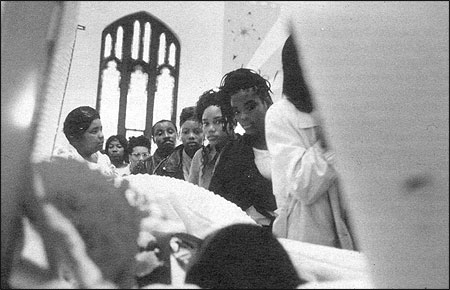

Funeral for a 13-year-old boy killed in a drive-by shooting.

The work I produced during these years often left more questions than answers. Indeed, there was light to be shed, but there was darkness, too. During the first year, I kept an eye out for reports of shootings or stabbings among youth. If I found an incident, I’d show up at the funeral and, with permission from the family, begin photographing. Some people wanted no part of me; others welcomed my presence as a way to bear witness to their pain and grief. One mother, unable to cope with the loss of her 12-year-old son, dove headfirst into the casket, knocking the body to the floor. To deal with this level of sorrow, I needed to cross into people’s inner depths of pain. The ability to do this is only accomplished through intense documentary work, and this involves a great deal of time.

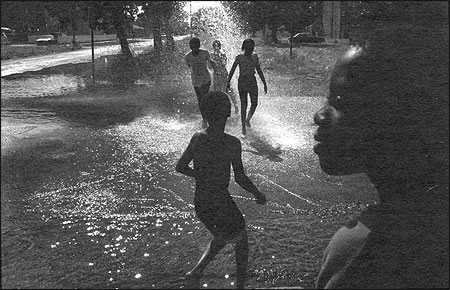

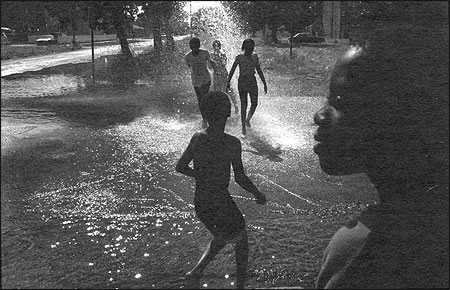

Two boys play at the Lexington Terrace public housing projects in West Baltimore.

After a year of working on this project, I had images attesting to the unrelenting violence, but another question lingered. What was producing it? I had befriended a young man who I knew had a drug problem. One day I asked him if he could take me into his community, a very tough project in West Baltimore. Through him, I met people who lived there. Often, when we’d arrive, we’d bring food from an organization I knew that collected food for the homeless. Neighbors began seeing my friend as someone other than a junkie, and they also began to trust me. Soon, they opened their doors—and their lives—to me. Deep documentary work is about sharing heart to heart. During this time I was with them, I was able to see and capture a much deeper perspective of their lives in this tough place. I understood that without light, without hope, dreams vanished. Love from someone, from anyone, remained the key.

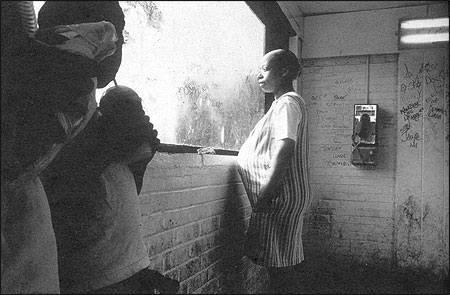

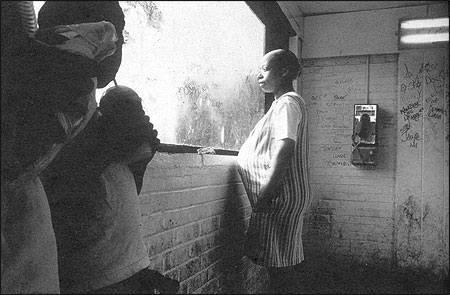

A pregnant woman looks out the window at the Robert Taylor Homes projects in Chicago.

In the end, I felt this project became a prayer. For me, it was a daily vigil to remember the amazingly painful lives that a small community in this country bear. That suffering is a part of our lives, too, because everyone is touched. I’ve made a conscious effort to keep returning to these communities and doing my work there, trying to shed light on those who have had hardship in their lives but have found their way. Their lives show hope. I want people to meditate on life and to understand that answers are often found in places of complete darkness. To show the light among us sometimes means grappling with the dark as well.

Andre Lambertson is a photographer based in New York City with the photo agency Saba Press and is a contract photographer with Time magazine. He has received several awards, including a Crime & Communities Media Fellowship from the Open Society Institute to continue his work on children and programs involved in the juvenile justice system. He is also working on a book, “Ashes,” a study of juvenile violence.

As I was photographing her, I was having a hard time finding a good location with the kind of light I wanted. I backed into a large room, filled with daylight, turned around, and found myself staring into the face of a dead 13-year-old boy. He was dressed in an off-white suit and his tiny frame squeezed tightly into a narrow casket. He seemed ready to open his eyes at any moment.

Sweat was rolling down my arm and, after a long moment of silence, this woman said, “That’s nothing new. It’s happening all the time.” She began to tell me about all the young people being killed and killing each other. She said that youngsters in the city had grown accustomed to death, to seeing its face up close, to visiting their friends in funeral homes, and talking about it as they might a social outing. It was one more party to dress up for, another occasion to wear black.

Her words shook me. It was after this experience that I began what was to become a five-year photographic journey into black neighborhoods of Baltimore, Chicago and New Orleans trying to understand and convey through images what was happening to their young.

Robert Taylor Homes projects in Chicago. Photo by Andre Lambertson.©

These youngsters endure the harsh realities of deprivation and racism. Many of these children attempt to shield themselves from an environment they find profoundly threatening. Beneath their stony exteriors there is trauma that outsiders rarely know. I was familiar with the work of some photographers who had tried to portray the poverty and despair within some black communities, but I didn’t feel the photographs conveyed insights deeper than the obvious circumstances. I wanted my work to help me and others understand why these neighborhoods continued to devour their children, how children who lived there saw themselves, and where they found hope. Most deeply, I wondered how I could help. After all, I was drawn to photojournalism because I felt it was a tool I could use to bring about positive change in people’s lives.

With a counselor from Gang Peace, a young man talks about available jobs.

I think that the best journalist is seldom subjective. Any journalist with enough curiosity and heart can tell any story if he asks the right questions of himself. To tell the best stories, he relies on his heart. He uses what he knows, often his own experiences, to get inside a story, to find its walls and penetrate them. Being black and adopted, I wondered how I would have fared in one of these communities. A loving and strong parent had helped me to find my path and stay out of harm’s way, and perhaps this made me want to tell these stories about children who didn’t have someone to do this for them. The biggest question I asked myself as I documented these children’s lives was why people don’t care more about why they are dying so young.

Boys playing cops and robbers at LexingtonTerrace, West Baltimore.

When I mentioned this idea of photographing these children and their communities, my editors back at the newspaper told me simply ‘Kids killing kids is nothing new. The story has been done.’ But I feel that it is the job of journalists to tell stories again and again in new and creative ways. By bringing a deeper, more complex way of examining the issues of juvenile violence, I wanted to shed light on the complicated conditions and issues that embraced these children. No one was born a killer. What happened along the way to make them do this? And I wondered how the mainstream press would have reacted if these children were white. Would this be considered an epidemic? Of course, this was before Columbine happened.

Cabrini-Green projects in Chicago.

My burning desire to be a photojournalist was fueled largely by my desire to be seen and heard and to give voice to those who aren’t heard. The apathy toward this story that I heard from my editors pushed me harder to do it. I wanted to show dimensions of these youngsters’ lives that would portray them in more sensitive ways. I felt the mainstream press often demonizes these youth.

Funeral for a 13-year-old boy killed in a drive-by shooting.

The work I produced during these years often left more questions than answers. Indeed, there was light to be shed, but there was darkness, too. During the first year, I kept an eye out for reports of shootings or stabbings among youth. If I found an incident, I’d show up at the funeral and, with permission from the family, begin photographing. Some people wanted no part of me; others welcomed my presence as a way to bear witness to their pain and grief. One mother, unable to cope with the loss of her 12-year-old son, dove headfirst into the casket, knocking the body to the floor. To deal with this level of sorrow, I needed to cross into people’s inner depths of pain. The ability to do this is only accomplished through intense documentary work, and this involves a great deal of time.

Two boys play at the Lexington Terrace public housing projects in West Baltimore.

After a year of working on this project, I had images attesting to the unrelenting violence, but another question lingered. What was producing it? I had befriended a young man who I knew had a drug problem. One day I asked him if he could take me into his community, a very tough project in West Baltimore. Through him, I met people who lived there. Often, when we’d arrive, we’d bring food from an organization I knew that collected food for the homeless. Neighbors began seeing my friend as someone other than a junkie, and they also began to trust me. Soon, they opened their doors—and their lives—to me. Deep documentary work is about sharing heart to heart. During this time I was with them, I was able to see and capture a much deeper perspective of their lives in this tough place. I understood that without light, without hope, dreams vanished. Love from someone, from anyone, remained the key.

A pregnant woman looks out the window at the Robert Taylor Homes projects in Chicago.

In the end, I felt this project became a prayer. For me, it was a daily vigil to remember the amazingly painful lives that a small community in this country bear. That suffering is a part of our lives, too, because everyone is touched. I’ve made a conscious effort to keep returning to these communities and doing my work there, trying to shed light on those who have had hardship in their lives but have found their way. Their lives show hope. I want people to meditate on life and to understand that answers are often found in places of complete darkness. To show the light among us sometimes means grappling with the dark as well.

Andre Lambertson is a photographer based in New York City with the photo agency Saba Press and is a contract photographer with Time magazine. He has received several awards, including a Crime & Communities Media Fellowship from the Open Society Institute to continue his work on children and programs involved in the juvenile justice system. He is also working on a book, “Ashes,” a study of juvenile violence.