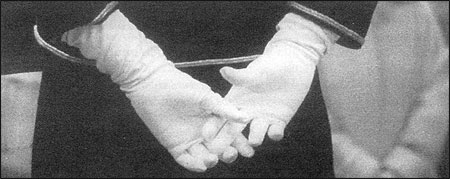

Jackie Kennedy’s gloved hands as seen in “Primary.”

In the early 1950’s, with television in its infancy, the ability to capture real-life moments as they happen and use those images to tell a story was little more than an idea of what the documentary approach on this new medium might become. I’d spent 10 years at Life as a correspondent and editor and experienced firsthand the powerful force that candid photography of real life can produce. And from my work on a magazine show for NBC, I knew that improving photography, writing and editing would not make the difference in creating this kind of effect on television.

What had to evolve was an editorial approach that valued reality captured with the intimacy of the still camera and the technology to allow this to happen in motion pictures. But once that happened—and we knew it would—those of us wanting to pursue this new type of reporting would need to know how to transform these sounds and images into documentary television.

During my Nieman year in 1955, I focused on two questions: Why are documentaries so dull? What would it take for them to become gripping and exciting? Looking for answers, several Harvard mentors steered me towards an exploration of basic storytelling. So I studied the short story, modern stage play and novel, and watched how some of these forms came across on TV.

By the time I felt I knew the answer, I was embarrassed at how long it had taken me to realize it. What I finally saw was that most documentaries were audio lectures illustrated with pictures. I watched Edward R. Murrow’s “See It Now,” but did so without sound, simply watching the picture. Its progression disintegrated. Then I turned the picture off and listened to the sound; the program tracked perfectly. Later, these TV programs were printed in book form and read very well.

The storytelling problem was beginning to sort itself out for me. Stories could be told in different ways, using different means of communication, but each medium had its unique strength for doing this. And its unique strength was, not surprisingly, its best. TV documentaries were dull because they misused the medium. The kind of logic that builds interest and feeling on television is dramatic logic. Viewers become invested in the characters, and they watch as things happen and characters react and develop. As the power of the drama builds, viewers respond emotionally as well as intellectually.

It was also becoming clearer to me that journalism is not relegated to one medium or another. It is a task to be combined with the means to communicate that which is discovered. And in TV the nightly news, for example, is one “medium,” doing what it does best, which is to summarize the news, often by lecturing with picture illustrations.

The prime-time documentary ought to be different. What it adds to the journalistic spectrum is the ability to let viewers experience the sense of being somewhere else, drawing them into dramatic developments in the lives of people caught up in stories of importance.

As my Nieman year progressed, my mission was becoming clear: convey experience. Leave the rest, the exposition, analysis, elucidation, to others in the media better suited to those tasks. Then, one evening, Omnibus presented a TV documentary, “Toby in the Tall Corn,” about a traveling tent show, that conveyed feeling and experience that was strong enough to overcome an inane narration.

I flew to New York and asked the executive producer, Bob Saudek, why “Toby” was so powerful. “Because I assigned Russell Lynes to write the narration,” he said.

I asked Russell Lynes the same question. “Because I focused the narration on the economics of the tent show,” he replied.

I found cameraman-director Richard Leacock at a moviola in the basement of a townhouse. Hardly looking up from his editing, he responded, “Because Russell Lynes wrote the narration.”

Leacock and I went out for coffee. I wanted to know how he’d been able to make this film look like it had been photographed candidly and spontaneously, when the bulky equipment and mistrained talent available to him made this nearly impossible to do. What we discovered that day was our mutual interest in making the impossible possible.

My Nieman colleagues, all of them newspaper people, were not shy about offering me a challenge. Often we debated into the night the question of what, if anything, all of this stuff about storytelling had to do with journalism. Back then, for me, storytelling was about trying to envision a new television journalism that allow the documentary to do what it does best. This meant leaving to other media what they can do best. The right kind of documentary programming should raise more interest than it can satisfy, more questions than it should try to answer.

When my year ended, I wrote an article for Nieman Reports entitled, “See It Then,” setting forth my ideas about this journey on which I was about to embark. It would take me five more years to conceive and develop the editing techniques, assemble the teams, reengineer the lightweight equipment, and find the right story to produce for my first TV documentary.

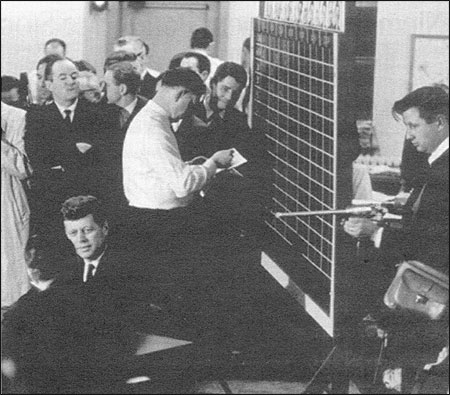

Finally, in 1960, with the camera hefted by Richard Leacock and the tape recorder carried by me, we set out to tell the story of a young man who wanted to be President. His name was John F. Kennedy, and our drama focused on his tough primary fight in Wisconsin. Though burdensome by today’s standards, the equipment made it possible for the first time for us to move the sync sounds camera-recorder freely with characters throughout a story.

The film was called “Primary” and is regarded as the beginning of American cinéma vérité.

Robert Drew, a 1955 Nieman Fellow, is an award-winning documentary producer. As an editor at Life, Drew specialized in the candid still picture essay. Among some hundred Drew films, those that established cinéma vérité in America include “Primary,” “On the Pole,” “Yanki No!,” and “Faces of November.”

Robert Drew holds the microphone.

“For five days and nights we recorded almost every move the candidates made, the sights and sounds of the campaign, and the way the public responded. For one sequence at a senstive time, Leacock and I split up. He filmed alone the tension in Kennedy’s hotel room as election returns came in. Four cameras converged on Kennedy’s victory. With twenty hours of candid film in hand, I was able to plan the editing of a story that would tell itself through characters in action, with less than two minutes of narration.”—Richard Drew

Richard Leacock holds the camera.