Paul Grondahl and Steve Jacobs didn’t expect to be following a funeral march through fields of maize in an impoverished Malawi village in the spring of 2003. They hadn’t imagined the groans of pain echoing off the bare cement floors of a crowded hospital, where patients waited in dark, filthy hallways for someone to die so a plywood bed would become available in a makeshift cholera ward.

Grondahl and Jacobs had each spent almost 20 years working for the (Albany) Times Union, and they knew that foreign reporting wasn’t often a part of the newspaper’s journalistic repertoire. Like most American newspapers, the Times Union recognizes that its franchise depends upon its local reporting. As the dominant daily in New York’s Capital Region, the newspaper also strives for leading coverage of state government and politics.

Why would our newspaper send a team to one of the poorest nations on earth, far away from the community we serve? Why would we publish a full-color, 24-page section featuring these journalists’ reports and devote countless hours to creating an ambitious presentation of this project on our Web site?

Deciding to Report in Africa

The Times Union’s so-called Africa project, “Fourth World/Our World: Lifelines at the Edge of Survival,” emerged as one of the newspaper’s most notable undertakings. When Grondahl, a reporter, and Jacobs, a photographer, were enduring sub-Saharan Africa’s stifling heat, with red mud caked on their boots and in their hair, they couldn’t envision standing in the spotlight in tuxedos at a National Press Club banquet, accepting a national award that recognized their innovative, insightful coverage. Nor could they know how many readers would be awakened to a humanitarian crisis of epic proportions, in a place where 20 million people face hunger and malnutrition, where more than 70 percent of the world’s HIV/AIDS cases are found, and where disease and hardship are expected to kill people before they reach the age of 40.

At the beginning of 2003, most American journalists, if they were looking overseas at all, were focusing on Iraq, where a U.S. invasion loomed. Thinking that the Times Union might embed a team with American troops, I’d sent a reporter and photographer through a Pentagon training program.

But good journalists have a way of finding stories in places where other people don’t happen to look, and that’s what happened when Steve Jacobs went out on a daily photo assignment in early January. He shot photos of Emelita Williams, a local woman who was collecting supplies for a school that was being built in Malawi, not far from where she had been born. Williams had helped start construction of the unfinished school some years before, and she wanted to carry the supplies back and finish the project. Jacobs saw a larger story.

“Emelita will be going back to her homeland in just four weeks to help distribute the most recent supply shipment to the children at the school she helped build,” Jacobs wrote to me in a mid-January memo. “I propose to photograph this story, offering pictures of the Williams family at their jobs, at school, and at home in the Capital Region, as well as to show Emelita’s experience when she gives hope to the young faces in her native homeland, in Africa.”

I wasn’t convinced. One family’s humanitarian effort was a good story, but not so good that I could justify blowing the newsroom’s travel budget for an entire quarter. Jacobs, undeterred, enlisted Grondahl, the newspaper’s most honored reporter. The two had traveled together to Northern Ireland a few years ago, tracking links to our community’s sizeable Irish population, and had collaborated on groundbreaking projects involving state prisons and mental health facilities.

Meanwhile, I had grown uneasy with the notion of embedding anybody from the Times Union in Iraq. I wondered: What unique reporting could we do? Editors at papers the size of the Times Union (about 100,000 daily and 145,000 Sunday) too often send staffers to faraway places more for their own ego enhancement than for journalistic merit. How could I justify spending so much money just to put a Times Union byline on a war story that could be produced just as ably by any of the various sources available on our wires?

Five days after Jacobs’ initial memo, President Bush surprised listeners when in his State of the Union address he called for $15 billion in spending over five years “to turn the tide against AIDS in the most afflicted nations of Africa and the Caribbean.” That, I thought, might focus our readers’ attention on Africa, perhaps giving more relevance to Emelita’s story. Grondahl dropped me a note. “We could do a two-for-one trip,” he suggested, “in which we’d spend a couple days with the Williams family at the new school and the arrival of food and supplies and then branch out and do an AIDS epidemic story.” After talking it over with Managing Editor Mary Fran Gleason, I asked Grondahl to do some preliminary reporting on a single broad project, one that would examine the humanitarian crisis in Africa through the prism of Emelita’s story.

Grondahl’s subsequent memo the next week convinced Gleason and me that this was the kind of foreign reporting worth undertaking. “We propose to tell the epic tragedy of Africa—drought, famine, AIDS, political corruption, and a steady march of death and devastation—through the moving story of a [local] family and its struggle to save a small group of AIDS orphans in a tiny village in Malawi,” it began. He estimated total cost of travel at less than $4,000.

Just three weeks later, as hundreds of other journalists were joining U.S. troops massing for the Iraq invasion, Grondahl and Jacobs took off for Malawi. They stayed for 16 days.

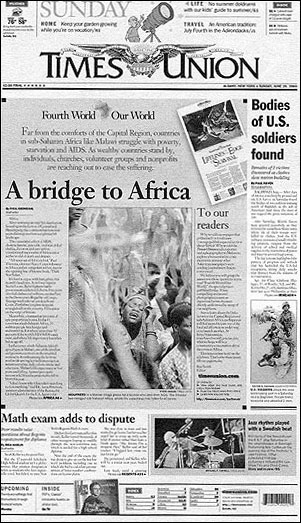

The newspaper's front page for its special section on Africa.

The second page of the Africa reporting, including a map and key facts.

The Web and Newspaper Presentations

We knew these two veteran journalists would come back with plenty of material for whatever kind of project we might want to publish. But Grondahl and Jacobs also had prepared to present their work on www.timesunion.com, our Web site, which for several years has enhanced our newspaper’s storytelling in visually dynamic ways. So they packed among their reporting tools equipment for digital audio and video recording. Experience has taught us that when we plan our Web reporting as an integral part of the overall package, both the print and online versions of the story are strengthened. We weren’t wrong: Each of these presentations offered readers different ways to engage with the information our reporters brought home.

During their pre-trip reporting, Grondahl and Jacobs also had come across a few humanitarian efforts in sub-Saharan Africa that are based in the Capital Region. Those efforts turned out to be an unexpected but major thrust of the project. Not only did those projects, in turn, lead to others that Grondahl and Jacobs visited in Africa, but also in the weeks after the team returned their reporting focused on other Capital Region links to sub-Saharan Africa. The story of Emelita Williams became but one element of the overall package.

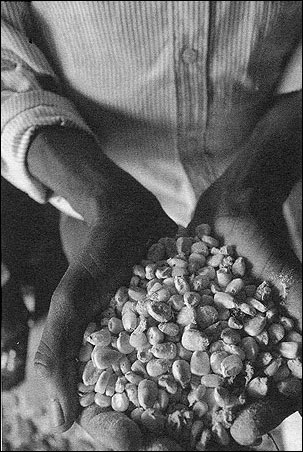

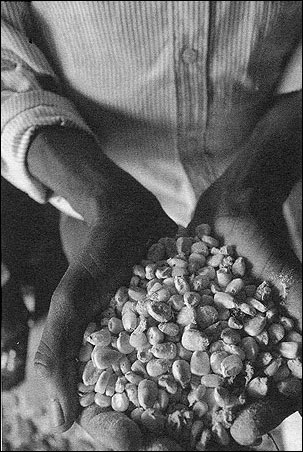

A Malawian holds a handful of maze, a native corn-like food that people use as their primary food source. March 2003.

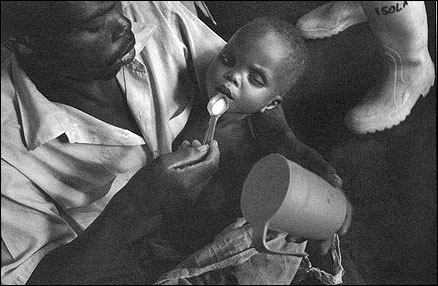

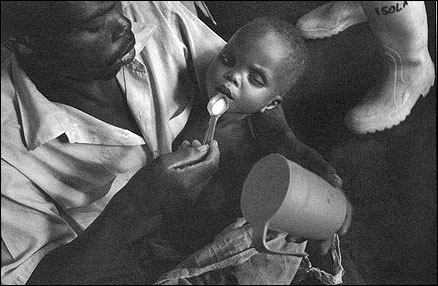

A Malawian child, sickened by cholera and AIDS, is fed by a villager in a makeshift hospital. March 2003.

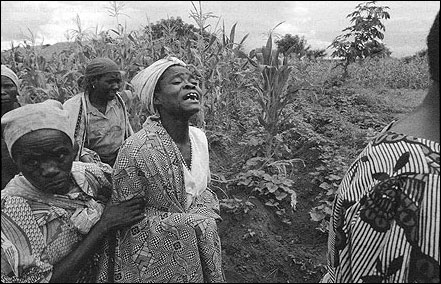

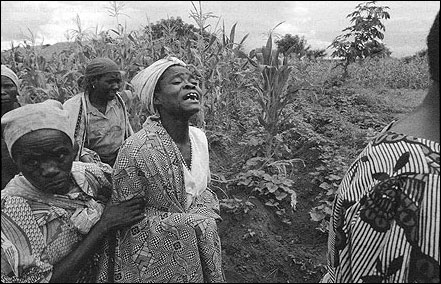

Elderly Malawian women openly cry, yell and grieve as they walk to the village burial grounds during a traditional funeral service for a woman who died of AIDS. The women walk separately from the men. Malawi, March 2003.

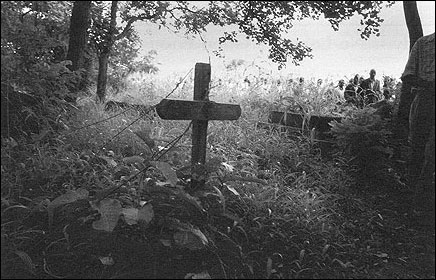

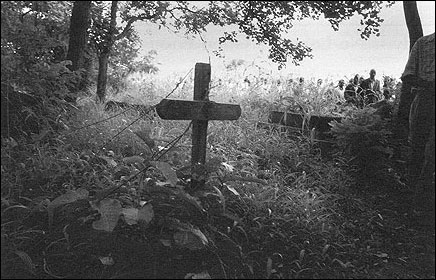

Malawian men and women, in the background, pass the grave of a villager that is marked wih a cross deep in the bush fields. Malawi, March 2003.

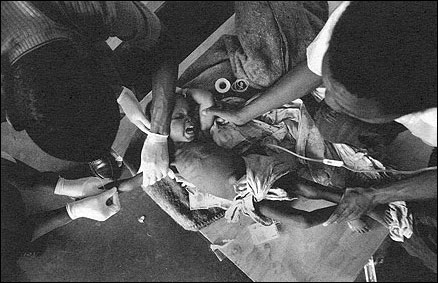

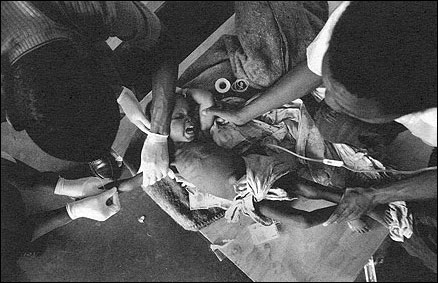

To combat dehydration, medical workers struggle to start an intravenous drip in the arm of a two-year-old boy stricken by cholera during an outbreak in the village of Madisa, Malawi. March 2003.

Photos by Steve Jacobs/Times Union.

Malawi is a country roughly the size of Pennsylvania. Among the 192 nations of the world, Malawi’s life expectancy ranks 186th and its per capita gross national product ranks 189th.Grondahl would later write that it was “so desperately poor and in such an utter state of collapse that it doesn’t even qualify as a member of the underdeveloped Third World.” Amazingly, he found, it also was too poor to qualify for the aid dollars that Bush had promised to alleviate the suffering of AIDS in Africa.

As a journalist, Grondahl has more finely tuned senses than most of us. He sees and hears, tastes, smells and touches more than most reporters, and it all goes into his notebook, from which he extracts strands of stories that he braids together into eloquent prose. A challenge upon his return was to draw out this remarkable reporting and writing without letting it yield an unwieldy batch of mainbars and sidebars.

The solution was to present the entire package as a series of short stories, linked under “chapter” headings, with no single piece dominating the package. All of it would be published on a single day, in a section that we realized would cover several pages. We wanted to present Jacobs’ powerful photography in color, but we knew that wouldn’t be possible on the Times Union’s 34-year-old press. We enlisted our marketing department to find sponsors who would pay for high-quality printing offsite.

What emerged on the last Sunday of June 2003 is what we view as a prototype of contemporary reporting, in a form we have roughly mimicked in presenting other projects since then. In addition to the Africa project’s dramatic Web presentation, readers of the paper found a 24-page full-color section (including 2 1/2 pages of sponsorship) that presented 80 photographs and dozens of articles, divided under three chapter headings: “Affliction,” “Affirmation” and “Cooperation.” The voices of experts, rather than intruding into Grondahl’s descriptive narratives, were pulled out as Q&A segments along the bottom of the pages. Personal insights that augmented the storylines were offered in nine installations of a reporter’s journal. A full-page map pinpointed the humanitarian efforts that Capital Region groups and congregations had launched in Africa. On the front page of the newspaper, a more traditional story introduced the special section inside, exploring the policy issues that stood in the way of progress toward solving the crisis. In all, 16 journalists at the newspaper worked on delivering this project to our readers.

We heard many comments from readers, most of whom had never known of the many links between our community and a part of the world so badly scarred by poverty and disease. But we were also struck, sadly, by how quickly the story seemed to vanish from our readers’ consciousness. If we created a community dialogue, as we had hoped to do, in part through our interactive Web site, it was a quiet one, heard largely in the places where such conversations might be expected to take place anyway: houses of worship and a few schools.

We had done our best to present a vital issue to our readers, not imagining that we could change the world, of course, but confident that we would make things a bit better. And perhaps we did that, and maybe that’s all a newspaper can hope for when trying to present a serious issue from a distant land to a readership distracted by war and politics and entertainment and the busyness of everyday life. What we did might have helped forge some enduring connections. For those of us who tried to connect our world with theirs, we believe firmly it was worth the effort.

Rex Smith is editor of the Times Union in Albany, New York. “Fourth World/Our World” won the 2003 Scripps Howard National Journalism Award for Web Reporting. (The Africa project can be found at www.timesunion.com/fourthworld.)

Grondahl and Jacobs had each spent almost 20 years working for the (Albany) Times Union, and they knew that foreign reporting wasn’t often a part of the newspaper’s journalistic repertoire. Like most American newspapers, the Times Union recognizes that its franchise depends upon its local reporting. As the dominant daily in New York’s Capital Region, the newspaper also strives for leading coverage of state government and politics.

Why would our newspaper send a team to one of the poorest nations on earth, far away from the community we serve? Why would we publish a full-color, 24-page section featuring these journalists’ reports and devote countless hours to creating an ambitious presentation of this project on our Web site?

Deciding to Report in Africa

The Times Union’s so-called Africa project, “Fourth World/Our World: Lifelines at the Edge of Survival,” emerged as one of the newspaper’s most notable undertakings. When Grondahl, a reporter, and Jacobs, a photographer, were enduring sub-Saharan Africa’s stifling heat, with red mud caked on their boots and in their hair, they couldn’t envision standing in the spotlight in tuxedos at a National Press Club banquet, accepting a national award that recognized their innovative, insightful coverage. Nor could they know how many readers would be awakened to a humanitarian crisis of epic proportions, in a place where 20 million people face hunger and malnutrition, where more than 70 percent of the world’s HIV/AIDS cases are found, and where disease and hardship are expected to kill people before they reach the age of 40.

At the beginning of 2003, most American journalists, if they were looking overseas at all, were focusing on Iraq, where a U.S. invasion loomed. Thinking that the Times Union might embed a team with American troops, I’d sent a reporter and photographer through a Pentagon training program.

But good journalists have a way of finding stories in places where other people don’t happen to look, and that’s what happened when Steve Jacobs went out on a daily photo assignment in early January. He shot photos of Emelita Williams, a local woman who was collecting supplies for a school that was being built in Malawi, not far from where she had been born. Williams had helped start construction of the unfinished school some years before, and she wanted to carry the supplies back and finish the project. Jacobs saw a larger story.

“Emelita will be going back to her homeland in just four weeks to help distribute the most recent supply shipment to the children at the school she helped build,” Jacobs wrote to me in a mid-January memo. “I propose to photograph this story, offering pictures of the Williams family at their jobs, at school, and at home in the Capital Region, as well as to show Emelita’s experience when she gives hope to the young faces in her native homeland, in Africa.”

I wasn’t convinced. One family’s humanitarian effort was a good story, but not so good that I could justify blowing the newsroom’s travel budget for an entire quarter. Jacobs, undeterred, enlisted Grondahl, the newspaper’s most honored reporter. The two had traveled together to Northern Ireland a few years ago, tracking links to our community’s sizeable Irish population, and had collaborated on groundbreaking projects involving state prisons and mental health facilities.

Meanwhile, I had grown uneasy with the notion of embedding anybody from the Times Union in Iraq. I wondered: What unique reporting could we do? Editors at papers the size of the Times Union (about 100,000 daily and 145,000 Sunday) too often send staffers to faraway places more for their own ego enhancement than for journalistic merit. How could I justify spending so much money just to put a Times Union byline on a war story that could be produced just as ably by any of the various sources available on our wires?

Five days after Jacobs’ initial memo, President Bush surprised listeners when in his State of the Union address he called for $15 billion in spending over five years “to turn the tide against AIDS in the most afflicted nations of Africa and the Caribbean.” That, I thought, might focus our readers’ attention on Africa, perhaps giving more relevance to Emelita’s story. Grondahl dropped me a note. “We could do a two-for-one trip,” he suggested, “in which we’d spend a couple days with the Williams family at the new school and the arrival of food and supplies and then branch out and do an AIDS epidemic story.” After talking it over with Managing Editor Mary Fran Gleason, I asked Grondahl to do some preliminary reporting on a single broad project, one that would examine the humanitarian crisis in Africa through the prism of Emelita’s story.

Grondahl’s subsequent memo the next week convinced Gleason and me that this was the kind of foreign reporting worth undertaking. “We propose to tell the epic tragedy of Africa—drought, famine, AIDS, political corruption, and a steady march of death and devastation—through the moving story of a [local] family and its struggle to save a small group of AIDS orphans in a tiny village in Malawi,” it began. He estimated total cost of travel at less than $4,000.

Just three weeks later, as hundreds of other journalists were joining U.S. troops massing for the Iraq invasion, Grondahl and Jacobs took off for Malawi. They stayed for 16 days.

The newspaper's front page for its special section on Africa.

The second page of the Africa reporting, including a map and key facts.

The Web and Newspaper Presentations

We knew these two veteran journalists would come back with plenty of material for whatever kind of project we might want to publish. But Grondahl and Jacobs also had prepared to present their work on www.timesunion.com, our Web site, which for several years has enhanced our newspaper’s storytelling in visually dynamic ways. So they packed among their reporting tools equipment for digital audio and video recording. Experience has taught us that when we plan our Web reporting as an integral part of the overall package, both the print and online versions of the story are strengthened. We weren’t wrong: Each of these presentations offered readers different ways to engage with the information our reporters brought home.

During their pre-trip reporting, Grondahl and Jacobs also had come across a few humanitarian efforts in sub-Saharan Africa that are based in the Capital Region. Those efforts turned out to be an unexpected but major thrust of the project. Not only did those projects, in turn, lead to others that Grondahl and Jacobs visited in Africa, but also in the weeks after the team returned their reporting focused on other Capital Region links to sub-Saharan Africa. The story of Emelita Williams became but one element of the overall package.

A Malawian holds a handful of maze, a native corn-like food that people use as their primary food source. March 2003.

A Malawian child, sickened by cholera and AIDS, is fed by a villager in a makeshift hospital. March 2003.

Elderly Malawian women openly cry, yell and grieve as they walk to the village burial grounds during a traditional funeral service for a woman who died of AIDS. The women walk separately from the men. Malawi, March 2003.

Malawian men and women, in the background, pass the grave of a villager that is marked wih a cross deep in the bush fields. Malawi, March 2003.

To combat dehydration, medical workers struggle to start an intravenous drip in the arm of a two-year-old boy stricken by cholera during an outbreak in the village of Madisa, Malawi. March 2003.

Photos by Steve Jacobs/Times Union.

Malawi is a country roughly the size of Pennsylvania. Among the 192 nations of the world, Malawi’s life expectancy ranks 186th and its per capita gross national product ranks 189th.Grondahl would later write that it was “so desperately poor and in such an utter state of collapse that it doesn’t even qualify as a member of the underdeveloped Third World.” Amazingly, he found, it also was too poor to qualify for the aid dollars that Bush had promised to alleviate the suffering of AIDS in Africa.

As a journalist, Grondahl has more finely tuned senses than most of us. He sees and hears, tastes, smells and touches more than most reporters, and it all goes into his notebook, from which he extracts strands of stories that he braids together into eloquent prose. A challenge upon his return was to draw out this remarkable reporting and writing without letting it yield an unwieldy batch of mainbars and sidebars.

The solution was to present the entire package as a series of short stories, linked under “chapter” headings, with no single piece dominating the package. All of it would be published on a single day, in a section that we realized would cover several pages. We wanted to present Jacobs’ powerful photography in color, but we knew that wouldn’t be possible on the Times Union’s 34-year-old press. We enlisted our marketing department to find sponsors who would pay for high-quality printing offsite.

What emerged on the last Sunday of June 2003 is what we view as a prototype of contemporary reporting, in a form we have roughly mimicked in presenting other projects since then. In addition to the Africa project’s dramatic Web presentation, readers of the paper found a 24-page full-color section (including 2 1/2 pages of sponsorship) that presented 80 photographs and dozens of articles, divided under three chapter headings: “Affliction,” “Affirmation” and “Cooperation.” The voices of experts, rather than intruding into Grondahl’s descriptive narratives, were pulled out as Q&A segments along the bottom of the pages. Personal insights that augmented the storylines were offered in nine installations of a reporter’s journal. A full-page map pinpointed the humanitarian efforts that Capital Region groups and congregations had launched in Africa. On the front page of the newspaper, a more traditional story introduced the special section inside, exploring the policy issues that stood in the way of progress toward solving the crisis. In all, 16 journalists at the newspaper worked on delivering this project to our readers.

We heard many comments from readers, most of whom had never known of the many links between our community and a part of the world so badly scarred by poverty and disease. But we were also struck, sadly, by how quickly the story seemed to vanish from our readers’ consciousness. If we created a community dialogue, as we had hoped to do, in part through our interactive Web site, it was a quiet one, heard largely in the places where such conversations might be expected to take place anyway: houses of worship and a few schools.

We had done our best to present a vital issue to our readers, not imagining that we could change the world, of course, but confident that we would make things a bit better. And perhaps we did that, and maybe that’s all a newspaper can hope for when trying to present a serious issue from a distant land to a readership distracted by war and politics and entertainment and the busyness of everyday life. What we did might have helped forge some enduring connections. For those of us who tried to connect our world with theirs, we believe firmly it was worth the effort.

Rex Smith is editor of the Times Union in Albany, New York. “Fourth World/Our World” won the 2003 Scripps Howard National Journalism Award for Web Reporting. (The Africa project can be found at www.timesunion.com/fourthworld.)