RELATED ARTICLE

"Looking Beneath the Surface of Stories in Iraq, Iowa and Rwanda"Melissa Ludtke, editor of Nieman Reports, spoke with Brian Storm, founder and president of MediaStorm, a production studio based in Brooklyn, New York, which publishes multimedia social documentary projects at www.mediastorm.org and produces them for other news organizations. Trained as a photojournalist, Storm worked in multimedia at MSNBC.com and Corbis where he pioneered approaches to showcasing visual journalism in new media. In their conversation Ludtke and Storm discuss the limitations of photography in a time of digital media and Storm explains how the work of photojournalists can evolve to tell more compelling and complete visual narratives. Storm believes photojournalists, in developing new business models, can gain greater control over how and when their images are used. An edited transcript of their conversation follows:

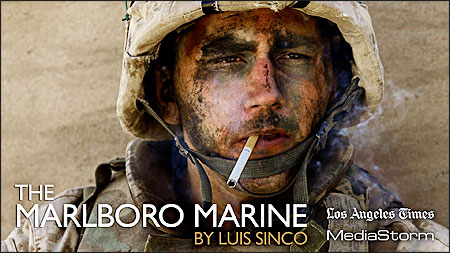

Melissa Ludtke: Let’s begin by talking about a photograph taken in Iraq by Los Angeles Times photojournalist Luis Sinco. His photograph of Marine Lance Corporal James Blake Miller, battle weary, with a lit cigarette in his mouth, became an iconic image, in your words, of the “macho bad-ass American Marines in Iraq.” I once heard you say that it was in the media’s response to this photo that you could see what’s wrong with photography as a medium today. Can you explain why this is so and where this thinking leads you?

Storm was also interviewed in the Spring 2009 issue of Nieman Reports.Brian Storm: It wasn’t about what’s wrong with photography, but this image underscored one of the great limitations that a single photograph has. It’s that we each bring our own perspective, our backgrounds, and our own prisms to a photograph because still images inherently lack the context—the rest of the story. The captured moment doesn’t tell you what happened before or after, though it can be incredibly powerful in getting you into an emotional state. I feel photography needs to have context around it to be the powerful storytelling mechanism that we’re trying to create here at MediaStorm in a multimedia format.

Ludtke: At MediaStorm, working with Sinco and Miller, you’ve created the multimedia presentation “The Marlboro Marine,” developed around this image. And it turns out that this Marine’s story is much different from this photograph—viewed as an iconic image—might have made it seem.

Storm: Very quickly the photograph became labeled as “The Marlboro Marine,” which is quite a title to give a picture. It created a lot of conversation, was published widely, but it’s not an accurate representation of the real story. James is a human being who as tough and macho as he looks is dealing with incredibly severe post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) from what he experienced in Iraq. Some estimate that up to 30 percent of our soldiers returning from conflict are dealing with PTSD. While he may look tough, his life has been turned upside down by what he’s experienced, causing incredible conflict at home and in his life. He filed for divorce and he’s tried to kill himself. He’s really, really struggling with life. No picture conveys that in a way that a 16-minute documentary does when it gives him a voice and allows him to tell his story. Of course, Luis Sinco’s experience on that story is also very compelling—his relationship with Miller and the many ways he crossed that line as a journalist where you get heavily involved with your subject.

Ludtke: Does this speak to your vision for a photojournalist’s role in the future? To step away from shooting the image and do what? Engage with the subject more directly? What then is the difference from a photojournalist’s work 10 years ago to now in the way that you envision this?

Storm: The biggest difference is slowing down and spending more time with the subject. It’s not just taking their picture; it’s giving them a voice. To do that, it’s not just using an audio recorder or a video camera to do interviews. It’s asking questions which allow the subject to give context to the story—to provide the rest of the information needed to truly understand the power of those moments. I’m not suggesting at all that we stop taking still pictures; they are an incredibly powerful way to communicate. But photographs require context to tell a more complete narrative. The best thing for photojournalists to do is to slow down, become a little more engaged, and spend a little more time on their projects in a much more intimate way.

Ludtke: What training is necessary for extraordinary photojournalists, who have proven themselves in the old way of doing things, to get them to where they’re going to feel comfortable moving in this direction? Or able to do it?

Storm: Photographers are inherently technical so adding audio and video is not a huge leap for them. Yet audio and visual storytelling are crafts. To become a truly terrific radio reporter is hard work. It takes the same kind of study and continual practice that becoming a great photojournalist takes. Video is exponentially harder because you are dealing with a lot of things all together at once—visual sequencing, motion, audio levels, moments and so on. So I’ve always tried to encourage photographers to start by using audio only. They’re already very visual people. And many of them are already spending quality time with their subjects. The biggest challenge is, as a photojournalist, we’re taught to be a fly on the wall; we are taught to not engage with our subjects. Our job is to disappear, become small and invisible so that a subject can do exactly what they’re going to do without any coaching or any “can you do that again?” kind of thing, which is pretty common in the video world.

In a lot of ways that’s why photojournalists are so well positioned to do these kinds of in-depth stories because they already know how to disappear. But at some point along that arc of reporting, a photojournalist needs to break that wall and say, “I know I’ve told you that I’m not here, I know I’m trying to disappear from your life and document it as it is, but I really want to sit down and ask you some very specific questions.” And that’s a different kind of journalistic experience than I think photojournalists are used to having.

There’s real tension around that. Why do it? When? And how? What questions can you ask? How do you ask them? All very important skills that photojournalists need to grow to do these kinds of stories. They’re not new skills that haven’t been developed by those in radio or broadcast so it’s not like we need to reinvent how to do it from the ground up. It’s not black magic but it is a craft and to do this in a way that is powerful and compelling is a skill that takes time to learn. You have to do these kinds of interviews a lot before you get to where it works well.

What we try to do in our workshop is underscore how these are singularly crafted skills. One of the great challenges is to have one person do it all. It’s very complicated. But take a story like “The Marlboro Marine.” No question that Luis was the right person to have those conversations because of their relationship and intimacy gained through his coverage. A trust has been developed, and Luis knows James’s story better than anyone. So this is not a daily turnaround; it required several years to play out, and it’s still playing out. In those cases of long-form, in-depth coverage, I think the single vision is ideal. And that’s where bringing multimedia skills to the reporting process is really critical.

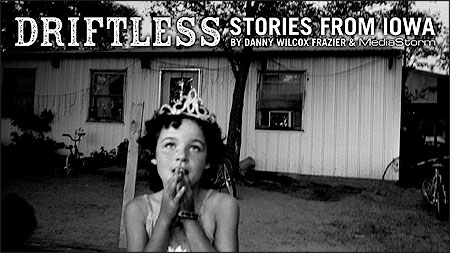

Stories that are covered over a long period of time with a singular vision are very powerful to me. But it’s rare for one person to have all of these skills. Collaborative teams to which people bring their expert skills are very powerful. Take Danny Wilcox Frazier who did “Driftless: Stories from Iowa.” That is five years of work by a world-class photojournalist that was published in a beautiful book. But there are only 4,000 copies of that book, and on MediaStorm’s Web site we had 10 times that many people watch the visual narrative of these stories on the first day it was live on our site.

So while the book is critical, it’s not the key element of a photojournalist’s franchise. The franchise includes the cinematic piece for broadcast, the Web, and mobile. There is also an exhibit and licensing of the project and still image for magazine publishing. Each of these elements has a role in the franchise. This is what we’re about—helping photographers realize their projects across multiple platforms so they can get the most exposure, reach the largest body of viewers, and generate the most revenue possible so that they can continue to do this type of in-depth, long-form work.

Ludtke: I recall you saying “If you’re a photojournalist today and all you do is editorial assignments, you’re dead. You have to have good syndication. You have to have multiple clients. You’ve got to do corporate jobs. You’ve got to do weddings. You’ve got to bust your ass.” Your example of Danny Frazier illustrates that, right?

Storm: A very good example. Having a diverse business model is critical for any small business. We don’t all have to shoot weddings but we need to think about creating a variety of opportunities for each project. Danny’s project also exemplifies what needs to happen in the reporting process. If Danny started that project with a vision for the franchise, I think he would have reported very differently. His vision was to create a beautiful book. But in my opinion that was not as complete as what we’re able to put together with additional reporting and collaboration. Danny partnered with Taylor Gentry, a terrific cinematographer, and they gathered video and conducted interviews after he’d already finished his book. Now what if Danny had those skills and had been gathering audio and video during the whole five-year period when he was doing this story? That would have been incredible.

Ludtke: Then what’s on MediaStorm would have been a contemporary project in that sense.

Storm: Yeah. With this one, we’re revisiting something where a photographer arrives with five years of work. “Isn’t this amazing?” he’ll say and I respond, “Yeah. But do you have audio?” That’s sort of our first question. Without that it’s really hard for us to take it into a cinematic state. So we’re trying to get visual journalists to go out with this understanding. Change the way you report and all of a sudden you have a product for distribution in many different formats.

Ludtke: This is what photographers need. This is the reality today. To be a photojournalist means a level of engagement across so many different platforms in media. It’s not just the photograph that’s destined for a single publication or a contract with one magazine.

Storm: There’s certainly room for photographers to focus on that, if that’s their choice. It’s just hard to argue with the impact that photographers can have if they evolve—evolve and become a more complete storyteller. The biggest payback is that really for the first time photojournalists have authorship. For so long, they have not had authorship in our craft. Usually they’ll shoot pictures, send them somewhere, and someone else picks which one goes in; often only one picture of a three-day shoot gets used. This is why for so long photographers have gravitated toward books as the premiere display of their work because they’re heavily involved in curating the edit and it is their prized possession. When a photographer gives you their book, they’re giving you a piece of their soul. It’s just this really important object for them because they have had that authorship.

Now, with multimedia, authorship jumps several octaves; you’re involved in a whole new way. In the epilogues of our pieces, Danny, for example, has the opportunity to tell how he put this project together, to talk about the rationale for why he did what he did, or how this project changed him as a person or to issue a call to action.

Ludtke: So a voice is not only given to the subject at the other end of the camera’s lens, but the photographer is speaking, too.

Storm: That’s an important issue. But I’d also caution that just doing multimedia with a photographer being interviewed isn’t enough. We need to be more aggressive in reporting and in doing interviews and gathering information while the project is in play. Because the story is not about us; it’s about the subject. The epilogue is incredibly valuable in terms of creating some transparency around who the photojournalist is who did the work because much of the public still thinks photojournalists are like paparazzi. And they’re not. These are hardcore journalists doing sophisticated storytelling, tackling important subjects, and providing information people need.

Ludtke: What remains a bit of mystery is how the high-quality photojournalists are going to find ways of being supported in the marketplace today.

Storm: That’s obviously the question because the profession is shrinking and we’re losing terrific journalists every day. Only the strong will survive. We’re going to lose some of our best people and that keeps me awake at night. Constantly on my mind during the last decade has been finding a way to solve this issue of our best photojournalists exiting the profession completely and losing institutional knowledge.

The solution relates back to photojournalists creating their franchise—having one client that you’re heavily reliant on is a recipe for a quick exit. Why take that approach when these new outlets are opening up and you can reach a larger audience and generate the kind of revenue needed to stay in business. And we’re not talking about millions of dollars.

Ludtke: We’re talking about having a decent career, decent living.

Storm: Exactly, and I think those opportunities are greater today than they’ve ever been.

Ludtke: They just have to be conceptualized in new ways?

Storm: Yes, and from the start of the reporting process. I’m excited about the next few years in this industry because I feel like people in the industry get it now. They understand they have to grow. Sure, it’s hard, but if it was easy to do, everyone would be doing it.

Ludtke: This brings my thinking back to the ubiquitousness of visual images—cameras on mobile phones; Flip video cameras; high-quality, highly mobile, HD hybrid cameras; and the digital ease of instantaneous global distribution. Makes one wonder how images are valued at a time when there are so many.

Storm: I’ve been thinking a lot about this lately, and I have to say this is the best thing that’s ever happened to our profession. The fact that everyone has a camera, that everyone can report and can publish on YouTube. They’re in the game. They are part of the process, and the audience now has a greater understanding of how hard it is to do what we do. And when they see something that’s truly special, I think it resonates with them in a way that it simply could not have 10 years ago because they’re part of the conversation. They are telling stories and they are completely engaged in the conversation.

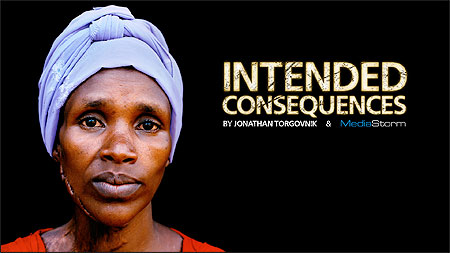

A decade ago, when I sat in a newsroom and everyone said to me, “Nobody’s going to watch a story about Rwanda. Nobody cares about Rwanda.” I always was like, “What are you talking about? Of course they’ll watch it. Of course they will care. We have to get them the product before they’re going to watch it and care about it. If we cut it off at the knees because we think they’re apathetic, it’ll never happen.”

The irony of what I see happening today is that the people who are apathetic right now are the ones who are sitting in newsrooms. They’re seeing their resources taken from them at such a prolific pace and they’re being asked to do more with less—right now the mainstream media has almost reached a level of apathy that’s paralyzing. But the audience that you just described is totally fired up. They’re totally engaged. They’re totally a part of the process of telling stories. And they are starving for good projects. And when they get them now, they spread them at a pace that we’ve never seen before via the statusphere and blogosphere.

Ludtke: So the digital distribution lines accentuate this?

Storm: Yeah, very much. We’ve never been in a situation where one person could, say, watch “Intended Consequences” [about Rwanda] and then turn around and post it on Facebook for their 600 or so friends. We’ve never been in that situation before where people could spread things as quickly as they can now. And what are they going to spread? They’re going to spread quality. It’s almost like a social currency now to say, “Hey, I think this is great.” That social currency just didn’t exist before. Now, you see something and immediately you curate that. Facebook is my new front page—it’s how I access information from around the world. My social network is shaping and curating for me what is important, and that is absolutely revolutionary.