Mike Kelly has worked at The Record for 46 years, and until Gannett acquired the New Jersey newspaper in 2016, he saw little need for a union.

But that changed once Gannett arrived. Kelly, a columnist for The Record, says Gannett chopped the newsroom’s staff from 190 in 2016 to 100 today and fired many of his fellow journalists in demeaning, callous ways.

“Our nationally known baseball writer was fired just eight hours after the last out of the World Series,” Kelly says. “One of our best investigative reporters — a Pulitzer finalist who was one of the first to expose Trump’s questionable deals in the New Jersey Meadowlands — was given just a few hours to clear out of the building.”

“I watched too many decent people stripped of their professional dignity,” Kelly continues. “We were watching our colleagues just pushed out the door willy-nilly and without any warning. I get that the newspaper business is in financial crisis. But you don’t take a person with 35 years experience and say you have an hour or [so] to clean out your desk. It’s not right.”

Related Reading

Why Newsrooms Are Unionizing Now

By Steven Greenhouse

From Covid-19 to #MeToo, The Labor Beat Is Resurgent

By Steven Greenhouse

Dismayed by the repeated rounds of layoffs, The Record’s newsroom employees (together with journalists at nearby Gannett-owned papers, the Daily Record of Morris County and the New Jersey Herald of Sussex County) voted 59 to 4 to unionize with The NewsGuild in May 2021. The papers were part of a unionization wave that has grown larger since journalists at Gawker Media became, in 2015, the first major digital media company to unionize. In the six years since, spurred by layoffs, increasing workloads, and even the pandemic, more than 100 news organizations have unionized, swelling the ranks of The NewsGuild, which has added about 6,300 new members over the past four years, and the Writers Guild of America, East, which has organized about 2,400 journalists since 2016. For these journalists, unionization has often meant higher minimum salaries, regularly scheduled raises, improved health coverage, greater protections against dismissal, and increased severance pay. The new unions have also pushed to increase diversity in newsrooms and eliminate pay gaps hurting women and minority journalists.

“People see other campaigns winning unionization votes and winning good contracts,” says Jon Schleuss, the NewsGuild’s president. “That has helped this spread like a wildfire, with people asking, ‘Would a union be possible here?’”

Hamilton Nolan, who was Gawker’s labor reporter, spearheaded the trend-setting union drive there at a time when many Gawker writers and editors were unhappy with the tradeoff the company offered: You get to do cool, fun work, but we’re not going to let you have a say in the company.

Immediately after Nolan announced the unionization effort, an unusually transparent debate erupted as Gawker employees posted their pro-union and anti-union positions online, making their dialogue accessible to the public. Explaining why he wanted a union, Nolan says: “You can talk about getting better wages, better benefits, editorial protections, all those important things, but regardless of how good your job is, if you’re not working under a contract, you’ll always be at the mercy of your boss if you don’t have a union.”

A big, unexpected factor helped the union effort: Gawker’s founder, Nick Denton — unlike many corporate executives — didn’t mount an anti-union campaign. Rather, Denton said he was “intensely relaxed” about it. In June 2015, Gawker’s employees voted, 80 to 27, to unionize with the Writers Guild. (Gawker Media, which also owned Jezebel, Deadspin, Gizmodo, and Jalopnik, went bankrupt in 2016 after losing a privacy lawsuit to Hulk Hogan.)

Within months of Gawker unionizing, journalists at HuffPost, Salon, Vice Media, and the Guardian US followed suit. By the end of 2018, 30 digital news outlets had unionized, along with what were long seen as the nation’s two most anti-union newspapers, the Los Angeles Times and the Chicago Tribune. The union wave soon swept up several prestigious magazines: The New Yorker, New York, and The New Republic.

Over the past few years, this wave has continued unabated. Journalists at The Atlantic and Forbes voted to unionize, as did over 500 workers from 28 Hearst publications, including Cosmopolitan, Esquire, and Good Housekeeping. Last June, editorial employees at the Insider website (formerly Business Insider) voted to unionize, 241-14, and in November, over 250 employees at Politico received union recognition. Slate, The Intercept, Talking Points Memo, Thrillist, Refinery29, and Chalkbeat, the education website, have also unionized. Writers and producers at The Ringer and Gimlet Media, two podcast giants, have unionized, as have numerous public radio stations, including WBUR in Boston and WHYY in Philadelphia, both of whose workers joined SAG-AFTRA, the giant union for radio, television, and movie workers.

“It’s pretty much ongoing nonstop,” says Nolan. “If anything has changed in the past few years, it’s the conventional wisdom around unions in the media. There was a time when in every conversation about organizing, people felt they were taking a big leap and they were really going out on a limb, but that has been mitigated to a large degree.”

Two major forces have propelled the unionization wave: the industry’s financial crisis and the wave of acquisitions, wiping out thousands of jobs and clamping down on salaries. Corporate owners like Gannett, GateHouse Media, and Alden Global Capital have sharply cut newsroom staffing and consolidated copyediting, layout, and graphics departments. In 2019, the firm that owns GateHouse purchased Gannett, forming a colossal chain with around 500 publications. Last May, Alden acquired Tribune Publishing and along with it, the Chicago Tribune, The Baltimore Sun, Hartford Courant, and the Daily News. Journalists at Tribune publications were so alarmed that Alden — which is often called a “vulture” hedge fund — might acquire their publications that they began a public campaign searching for alternative buyers. Alden has a record of making steep staffing cuts and selling off newspapers’ real estate assets to wring out profits. One study found that between 2012 and 2020, Alden cut staff by more than 75% at NewsGuild-represented papers after taking over.

Many journalists at Gannett papers have also joined the union wave, prompted by years of layoffs as well as fears that the GateHouse acquisition of Gannett would mean even more downsizing. Over the past few years, more than 15 Gannett papers have unionized, including The Arizona Republic, the Austin American-Statesman, and The Palm Beach Post. Tribune Publishing’s Hartford Courant unionized in 2019, and last April, the Daily News, once the nation’s highest-circulation paper, voted 55 to 3 to unionize. Last June, 140 journalists at 11 Southern California newspapers, including The Orange County Register and the Los Angeles Daily News, voted to unionize.

“People see other campaigns winning unionization votes and winning good contracts. That has helped this spread like a wildfire”

—NewsGuild president Jon Schleuss

Daniela Altimari, the Hartford Courant’s state house reporter, talks of devastation at her paper, where what was once a nearly 400-person newsroom has dwindled to having less than 30 reporters and one photographer today. “We saw things were getting bad,” she says, adding that things started a long slide after Tribune Publishing acquired the paper in 2000. “We had no idea how bad they’d get.” The Courant’s journalists finally decided to unionize in 2019.

More recently, the pandemic has also spurred unionization. With so many journalists working from home, isolated from each other, “there has been a greater desire to have a voice and a greater desire to have a community,” says Lowell Peterson, executive director of the Writers Guild of America, East. Other pandemic-related factors have similarly pushed journalists toward unions. “People want to have a voice in the protocols: testing, masking, vaxxing,” Peterson adds, noting that more journalists “want to push for the right to work at home,” not just for safety reasons, but also for work-life balance.

Concern about Covid-19 was one of the issues that led Stephanie Brumsey, a producer at MSNBC, and many of her co-workers to push to unionize with the Writers Guild. They were eager to have a voice on “whether we have to go back to the office,” she says, noting that management was pushing harder for a return to the office than many workers were comfortable with. “We definitely felt part of the unionization wave,” Brumsey says, adding that better pay and benefits were also a factor. “We looked at the company we love, and we wondered how we could make it better. We wanted to have more say.” In August, MSNBC’s workers voted 141 to 58 in favor of unionizing.

The thousands of newly unionized journalists have made some important gains. HuffPost’s current contract sets a $59,238 minimum for reporters starting in February, while The New Yorker’s contract sets a $60,000 minimum as of 2023 for the magazine’s employees. The NewsGuild said some employees had been making $42,000. In December, Vice Media’s union announced a contract that sets a $63,000 minimum pay by the end of 2024. Union contracts for journalists have also prohibited non-disclosure agreements that hide cases in which managers are accused of sexual harassment or discrimination. Many newsroom contracts now have diversity provisions, often similar to the one that The New Yorker agreed to: that at least half of the job candidates interviewed for open positions will come from underrepresented groups. And, in an industry with so much turmoil, union negotiators are frequently insisting on successorship clauses and improved severance pay. The Intercept’s successor clause, for example, says the union contract shall remain effective in the event the company is sold.

Back at The Record, workers were fuming when management said it wanted to phase out company-issued cell phones and pay a maximum of $50 a month toward phone bills. The newly formed union helped beat back that proposal. “We deserve a seat at the table for negotiating these things,” says Katie Sobko, a Record reporter for 11 years. “That has become increasingly necessary to ensure that we preserve and protect ourselves, our careers, and local journalism, as well.”

Low salaries were also a pivotal factor in unionizing, according to Sobko, adding that some Record reporters earn just $35,000 a year. “We live in one of the most expensive real estate markets in the world [North Jersey],” she says. “We don’t earn a living wage.”

Ever since The Record’s workers unionized, Gannett hasn’t laid off anyone at the paper, according to the president of The Record’s union. “I think that’s indicative of the power of the union,” says Kelly, the columnist. (Thomas C. Zipfel, Gannett’s labor relations counsel, has said, “We respect the right of employees … to make a fully informed choice for themselves whether to unionize or not to unionize.”)

Twenty-nine months after unionizing, employees at Wirecutter, a product-recommendation website owned by The New York Times Company, got their first contract, a 26-month deal that included immediate pay increases averaging around $5,000, as well as roughly 3% raises for each year of the contract. Salaries for the lowest-paid Wirecutter staff members would immediately increase 18%, according to union officials. The two sides reached an agreement in December, not long after all 65 members of the Wirecutter union went on strike from Black Friday through Cyber Monday — peak holiday shopping days — and urged consumers to boycott the site. The idea was to hurt The Times’ bottom line because when shoppers click from the Wirecutter website through to, say, Best Buy or Amazon, the Times Company often gets a percentage of the purchase price.

Many workers at Wirecutter were dismayed that it took more than two years to reach an agreement. The union asserted that The Times had intentionally dragged out negotiations (something The Times denied) as a way to discourage a unionization effort by roughly 600 of The Times’ tech workers. But Wirecutter isn’t the only newsroom to experience a long delay. At several outlets, workers who unionized two or more years ago still haven’t reached a first contract with their employer. That’s the case at BuzzFeed News, the Chicago Tribune, the Hartford Courant, The Arizona Republic, and NBC News.

Union leaders argue that many companies deliberately drag their feet in bargaining to sour workers on their unions. At BuzzFeed, which unionized in July 2019, employees say company officials may have delayed reaching a contract and offering substantial raises so as not to harm BuzzFeed’s initial public offering on Dec. 6. The week before, 61 Buzzfeed workers walked out for a day.

“I think that is a management tactic not only at BuzzFeed, but when I talk to chairs at other unions they say their companies are slow-walking this process,” says Addy Baird, a political reporter at BuzzFeed News and chair of its NewsGuild unit. “It’s really exhausting … It can be demoralizing.”

With inflation running at over 6%, Baird criticized BuzzFeed’s offer of a 1% across-the-board raise. “I think it’s insulting,” she says. “I know our members think the same way.” A BuzzFeed spokesman tells Nieman Reports that the company offered merit raises in addition to the 1% guaranteed increase. Meanwhile, the two sides have reached tentative agreement on more than a dozen issues, including remote work and grievance procedures.

“We deserve a seat at the table for negotiating these things. That has become increasingly necessary to ensure that we preserve and protect ourselves, our careers, and local journalism”

—Katie Sobko, Reporter at The Record

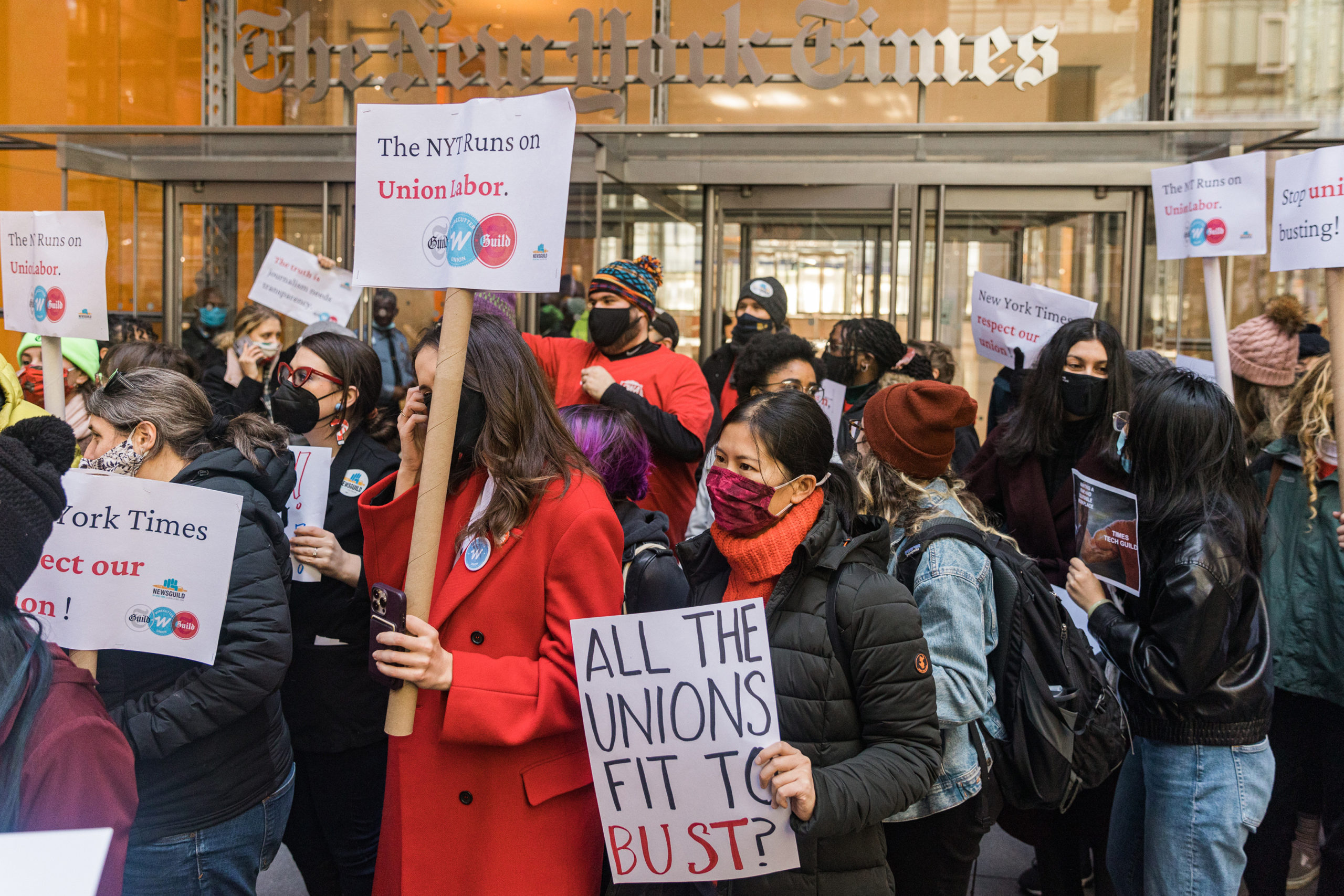

News employees, like workers in many other industries, often face opposition from their companies when they seek to form a union and bargain collectively. At The New York Times, many of the 600 tech workers have been trying to win union recognition since last April. If they are successful, the Times Tech Guild would be the nation’s biggest union of tech workers with collective bargaining rights. Times management is insisting on a unionization vote, refusing to recognize the union even though the NewsGuild says more than 70% of The Times’ tech workers have signed pro-union cards. (Under federal law, employers are required to grant union recognition if a majority of workers vote to unionize, but they don’t have to grant recognition based on the signing of pro-union cards.)

The Times rejected the request for voluntary recognition because “we’ve heard a significant amount of reservations and uncertainty among our technology and digital teams about what a union would mean for them,” says Danielle Rhoades Ha, The Times’ vice president for corporate communications. She adds: “We have a long history of productive relationships with our various unions.” The National Labor Relations Board said on Jan. 12 that it would mail ballots to The Times’ technical workers so they could vote on unionizing.

Nozlee Samadzadeh, a senior software engineer, said she was dismayed by The Times’ response to the unionizing efforts, which included urging workers to attend anti-union information sessions and what she called its “divide-and-conquer strategy.” The Times has proposed letting only software engineers join the Times Tech Guild, while leaving out more than 200 other workers, including product designers and project managers — though the NLRB rejected the attempt to split the group. “The message we get, particularly from Meredith [Kopit Levien, The Times’ President and CEO] is this patronizing one: ‘We don’t need a union. We’re all friends. We can figure it out,’” Samadzadeh says. “Which is pretty disrespectful in its own way.”

With 8.4 million subscribers, The Times is one of the financially stronger news organizations, in theory more able to give solid raises. But Emily Bell, director of the Tow Center for Digital Journalism at Columbia Journalism School, says unions would be misguided to treat all news organization as deep-pocketed. “We’re looking at a bifurcated industry,” she says. “You have the bigger, richer organizations making money, and quite a bit of it, and you have local outlets still really struggling.”

Bell says the unionization wave shouldn’t be a surprise. When many digital media companies were having a hard time hitting their financial targets, “the one way to get there was to squeeze staff,” she says. “The inevitable response to that was to unionize.”

But increased pay for journalists might hasten the demise of some news organizations. Bell says the upshot is: “You have prestige newsrooms making unionization a core part of their workplace. This perhaps builds a smaller, but more equitable industry.”