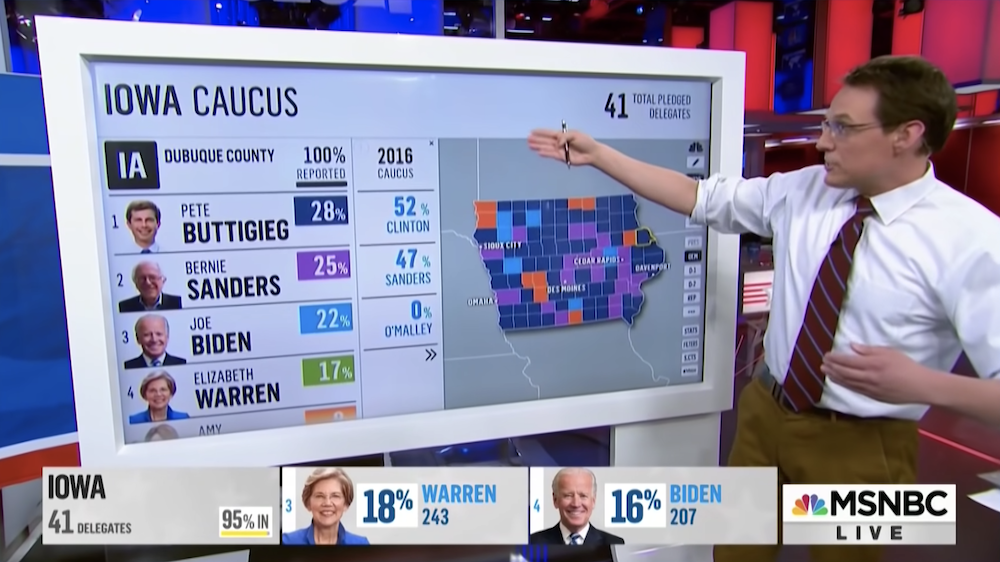

When it comes election night nightmares, Steve Kornacki has been there.

Kornacki, whose high-energy “big board” election analyses are a staple of MSNBC political coverage, recalls all too well how correspondents like him got stuck at the starting line of this most unusual election cycle.

He was standing by, ready to parse the results of the February 3 Iowa caucus on air — but the numbers just weren’t coming in. “We were hearing from the Iowa Democratic Party, ‘About 10 minutes … in about 10 minutes,’ and a producer must've asked me 48,000 times, ‘You got anything yet? You got anything yet?’ — and we never did. And we didn't get our first reported vote from that until, I think it was 4:30 or 5:30 in the afternoon the next day.”

The cable news networks’ job of covering the 2020 vote in real time could be complicated by what’s going right in terms of voter participation

The Iowa snafu — courtesy of the meltdown of a brand-new app used to tabulate caucus votes — meant the state Democratic Party didn’t certify its own results until February 29.

It was one small and unique example of something going wrong and causing public consternation, finger-pointing, and heavy complications for news outlets who devote heavy coverage to what has traditionally been an election-year bellwether. By comparison, the cable news networks’ job of covering the 2020 vote for president in real time could be complicated by what’s going right (so far) in terms of voter participation.

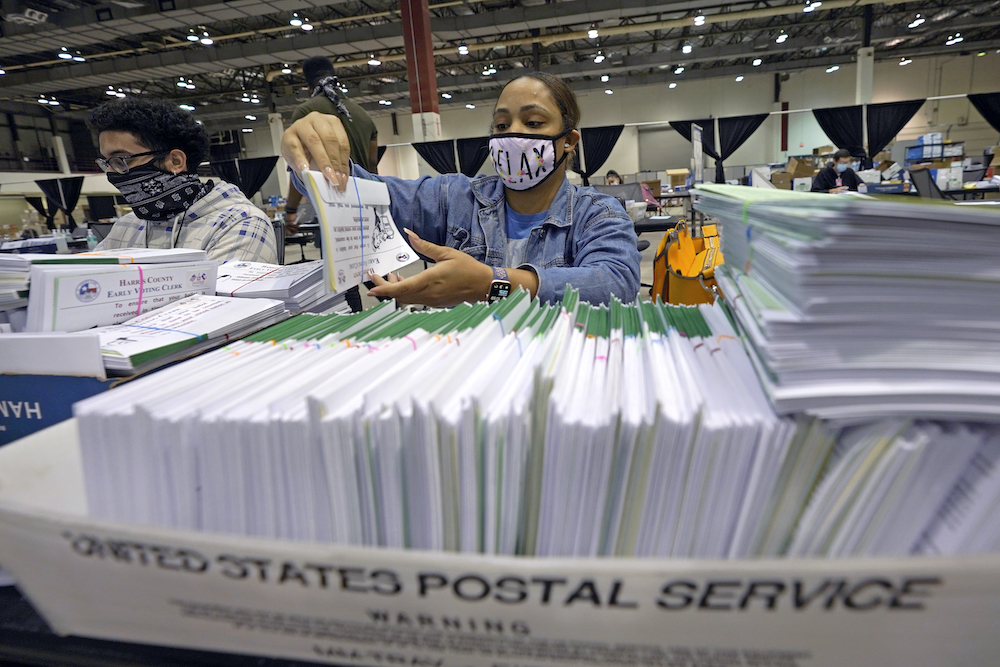

This time around, the Big Three cable networks — CNN, Fox, and MSNBC — have to contend with historically high levels of voting by mail, thanks to a deadly coronavirus pandemic. Voting by mail has been an efficient, effective part of American civic life dating back to at least the Civil War era, but the amount of time it takes to count those votes may be diametrically opposed to cable networks’ own recipe for success: Doing everything they responsibly can to break news first.

The pressure of competition in covering this momentous event — and getting it right — is heightened by a powder-keg political climate that has as its central figure incumbent President Donald Trump, who has made it a cornerstone of his re-election campaign to relentlessly and baselessly assail both the integrity of the election process itself and the news outlets that cover it (and him).

“There could be all sorts of so-called poll watchers hired by the Republicans to attempt to disrupt the vote, like they did in early voting in Virginia,” says Jerry Goldfeder, an election law attorney and prolific writer on the topic. “There could be such a huge number of mail-in ballots that it takes forever to count them, with an avalanche of litigation challenging those ballots, so we don't have results [by] the time [the Electoral College is] supposed to meet and vote on December 14th. And it could be just general civil unrest if the vote is close and the president just accuses everybody of vote fixing and [says] that it's illegitimate. The best-case scenario is if there are clear winners in enough states that the other side just can't challenge it.”

Election laws and rules, as political reporters have long known and explained, vary widely from state to state and even across counties, cities, and towns within those states. Getting all that information straight — and knowing where to focus, down to key precincts in key battlegrounds — is crucial for media outlets. It still may not allow them to make a call on election night itself, even if some states stick to more familiar ground when it comes to reporting day-of, in-person voting results after the physical polls close.

The horror of and fallout from a blown race call has loomed large in America’s newsrooms for years, possibly peaking in 2000, when some networks botched their award of a Florida win in the Bush versus Gore contest — not once, but twice.

It’s a responsibility that’s weighing on reporters, producers, and executives — particularly in a political season that was already hyperpartisan before the shockwaves of a pandemic and a national reckoning over racial justice — and it shows in how much time cable is putting into preparing coverage while also preparing viewers for an election that may last far longer than a night.

In August, for example, Arnon Mishkin, head of the Fox News Decision Desk, appeared on the "Fox News Rundown" podcast to warn it may be impossible to quickly hand a win to either Trump or his Democratic challenger, former Vice President Joe Biden. (Fox declined to be interviewed for this story, as did CNN.) Other TV giants have taken similar steps to explain how processing a surge of mail-in ballots could slow the timeframe for broadcasting results; in an October 7 explainer, Kabir Khanna, senior manager of elections for CBS, said the station "will not project a winner in a state until we're confident the trailing candidate won't catch up even after all ballots — whether cast in person or by mail, early or on Election Day — are counted." Some outlets are emphasizing “descriptive” rather than “predictive” models when it comes to analyzing election data.

Although each network has its own independent, sophisticated decision-desk operation, race calls from the Associated Press carry considerable weight throughout the industry. These calculations themselves, of course, aren’t new — the service has been accurately reporting U.S. election results since 1848. It’s the scale of by-mail voting that’s changing so dramatically.

To give a sense of scope, David Scott, deputy managing editor responsible for overseeing AP’s polling and race calls, points out that in the early 1970s, “almost everyone voted in person at their neighborhood polling place on Election Day.” By comparison, he says, “40% voted in advance in 2016 and 2018, and that number could go over 50%, and some surveys suggest maybe as high as 60%, in this year’s election … This trend toward voting before Election Day has been happening for many years, and the pandemic has just accelerated that and sort of squished maybe two or three decades-worth of transition into one election cycle.”

While AP has made some changes to its election coverage — including the launch of VoteCast, a new 50-state system for analyzing and sharing insights into voting behavior that will be used by cable networks including Fox and Univision this year — Scott says one thing won’t change: There have been years when AP has decided to hold off on calling a presidential contest on election night (including in 2000, 2004, and 2016), and if those benchmarks aren’t hit in 2020, it may happen again. “I don't want to predict what's going to happen,” Scott says. “We do the work to be prepared for whatever the voters decide.”

The issue for cable news, of course, is that having found that people have a desire for 24/7 coverage of major events, they now have to deliver it — whether there’s a winner or not.

“I think that part of the problem with cable is of their own making, because they have for years covered news events as though they were entertainment, with chyrons for going to war [or] as if it were the Super Bowl or something,” says Kathy Kiely, a veteran political reporter who now holds the Lee Hills Chair in Free-Press Studies at the Missouri School of Journalism. “I think some of it was well-intentioned; you want people to be interested in civic life, and so you try to make it more like a contest, but [that] then creates this expectation that we're going to have a nice, neat wrap-up when we’re supposed to.”

While news networks are now “starting to try to lay the expectation for something different,” she says, the fact remains that cable news networks, like other media, operate under commercial pressures that can push them toward the dramatic and the snap ending.

Even outlets whose whole existence is predicated specifically on calculating and disseminating race results — without all the other roles cable plays in shaping news and public opinion — are advising caution: “People sort of come for the show of election night and then go home, but those of us that work here, we know certified election results don't happen for three weeks, six weeks in some cases — and that’s normal,” says Drew McCoy, president of Decision Desk HQ, which has provided election data analysis for outlets as diverse as Reuters, Vox, and The Economist.

McCoy notes that Colorado Secretary of State Jena Griswold this month notably asked “national media executives” to refrain from making race calls while results were still up in the air — and later retracted her request after critics said limiting information about the election results could lead to confusion and suspicion. McCoy agrees with those critics, saying any kind of “news blackout would defeat the purpose of instilling confidence” in the election’s outcome.

In any event, media race calls, like victory or concession speeches by candidates, don’t determine the outcome of elections. Only voters do. However, reporting can heavily shape public perception and action. In this case, if anchors don’t have a perfectly timed cascade of state results to announce, and pundit panels don’t have the race calls they need to cheer or jeer the winner, how will cable news usefully fill the time in a way that both draws viewers and serves the public trust?

The horror of and fallout from a blown race call has loomed large in America’s newsrooms for years

“One of the things that benefits you [in terms of coverage is] you have all the House races, a third of the Senate and the presidency, as well as some interesting governor's races, so there’s a lot of things to look at,” says Mosheh Oinounou, a media consultant whose political reporting experience includes turns as a producer and editor at Fox, Bloomberg TV, and most recently CBS Evening News. “The challenge for programmers and producers [is], how do you [put] out a compelling election night product [in] a way that doesn’t overdramatize things, that ensures that you’re sticking to the facts, that doesn’t lead to too much speculation?”

To that end, Oinounou says, “it’s going to be more vital than ever that [cable networks] have a direct line into all of their local stations in those key states ... You know you’re going to see a random tweet get retweeted [by] the president, and the faster you can [put] your camera on Cleveland or in Philadelphia or Miami and actually see what’s going on, to verify what’s being said on social media, the quicker you can bring some calm to the country.”

Being there is important — but it’s unfortunately not always best for the bottom line, says Mike Conway, a media historian and associate professor of journalism at Indiana University.

With potential for long lines or trouble at poll sites, “There will be stories all across the country all night long. It’s whether or not the outlets have distributed their resources so they [cover] that, as opposed [to] kind of the lazy way of just turning to a pundit to give an opinion on something that we don’t know about. That’s usually where these outlets get into trouble — when they start speculating and relying on the pundits,” Conway says. “What we’ve seen over time is that outlets — especially on the cable end — have cut back on their crews covering stories around the country, and they rely more on these pundits because it’s a cheaper economic model.”

Debunking Trump’s misleading contentions in real time is generally complicated, and there’s a built-in dilemma about whether everything he says merits coverage because of his office, no matter how incendiary it may be. It certainly means the work of reporters and producers assigned to cover the mechanics of the voting process, specifically, is cut out for them.

When Trump uses a single, murky anecdote as grounds to try to cast broad-based doubt on voting by mail or another aspect of the system, “We can say that what he’s saying is wrong, but by the mere fact that we are talking about [it], it has now become ‘a thing.’ And I think about that stuff all the time,” says one woman covering the election for a top-three cable network who requested anonymity because she was not authorized to speak on behalf of her employer.

At her cable network, she says, “I know that we have for weeks talked about the reality that we probably won't know who’s going to win on election night — and the fact that it’s our responsibility to get people ready for that idea, so that when it happens, people aren’t like, ‘It’s a hoax,’ [but instead] they're like, ‘Oh, but this is what [you] said was going to happen for weeks. And now we’re listening to you.’”

MSNBC’S Kornacki says there’s been lots of discussion about how to handle potential snags and delays on November 3 — and the need to prepare viewers for the range of possibilities: “[If] the returns are pointing in a clear direction, they’ll call it on election night if that’s what the data's saying. But if it means it’s going to be three days, four days, five days, three weeks, it will be three days, four days, five days, three weeks. I think everybody is on board with that. Everybody is aware of the very kind of peculiar nature of the election.”

Celeste Katz Marston has spent 25 years reporting for newspapers, magazines, and radio with a specialty in politics, elections, and voting rights.