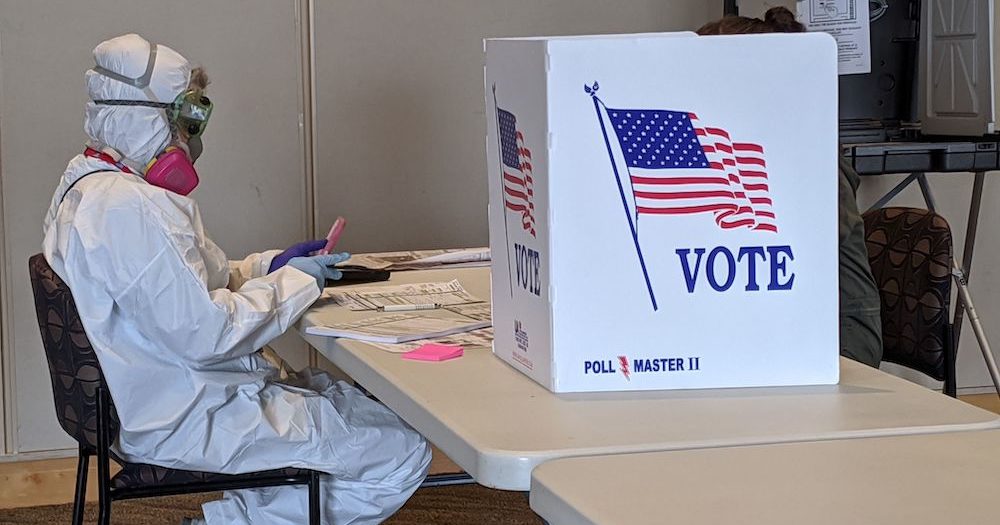

As Patrick Marley moved down the queue of voters lined up near a high school in Madison, some of his interviewees had to shout. Six feet apart is not ideal for a personal conversation about politics, especially on the tense Tuesday morning of Wisconsin’s primary elections on April 7. But the statehouse reporter for the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel was considerate, and the voters had a lot to say.

Between elbow bumps and squirts of hand sanitizer, Marley asked how they felt about standing in line to vote in the middle of a pandemic. Some were angry, some indifferent, some masked, some not. But for the most part, the sentiment echoed the now iconic image captured outside Milwaukee's Washington High School, where a masked woman named Jennifer Taff, who had waited in a line for two hours, held up a cardboard sign saying: “This is ridiculous.”

“In Wisconsin, we’re used to working in this frenzied environment,” says Marley, referring to the rest of his team at the Journal Sentinel. “What’s happening now is unlike anything I've ever covered.”

By this point, the team at the Journal Sentinel had been expecting to be doing nothing but campaign coverage. But as the deadly spread of Covid-19 cripples the United States, from coastal cities to rural townships, election coverage has largely taken a backseat to the novel coronavirus.

While Covid-19 has completely derailed coverage of the 2020 election campaign, it may, in a way, actually improve it. Every election, the media beats itself up about covering the horse race and not the issues. Now, with an extremely limited horse race to cover, journalists are covering the terrain: how the election even happens. With the coronavirus laying bare the gravity of election-related issues like income and racial inequality and access to health care, journalists are working overtime to report on perhaps the most consequential of them all: access to the ballot itself.

As the deadly spread of Covid-19 cripples the U.S., election coverage has largely taken a backseat to the coronavirus

Voting rights is a story of long lines, glitchy machines, bureaucracy, and legislation — a massive, sputtering apparatus long overdue for an inspection but sidelined by other political preoccupations. But with the novel coronavirus, journalists have a powerful lens with which to examine it. Even as the floundering economy drags an already struggling media industry down with it, political reporters are finding ways — in the face of furloughs and social distancing guidelines — to report a story that is less about who is running than how the election runs and who gets counted.

Related Reading

Vote and Die: Covering Voter Suppression during the Coronavirus Pandemic

By Brian Friedberg, Gabrielle Lim, and Joan Donovan

During the Coronavirus Crisis, Coverage of State Capitals Is More Essential than Ever

By Christopher Baxter

Election administration is “such a fundamental part of the campaign and election process that is under-covered and underappreciated and not understood like it should be,” says Stephen Fowler, an election reporter with Georgia Public Broadcasting Radio News. “This virus has given an opportunity to give an extra human layer [to the election process] that generally appeals to a few wonky people interested in election administration.”

The last time Ken Thomas saw Joe Biden in person was in an ice cream shop. It was Super Tuesday in East Los Angeles, and The Wall Street Journal reporter covering Biden’s campaign was standing behind the parlor counter with the press corps — a better angle — with Biden and LA Mayor Eric Garcetti on the other side. From across the display freezer, both sides bantered back and forth. The press fired off questions while the politicians got ice cream — Biden got chocolate chip — and mingled with the crowd.

“It seems every time we go to an ice cream shop, [Biden] takes questions,” says Thomas.

That was March 3, when the campaign trail was full of color, frenzy, and engagement. Thomas had followed Biden across the country — Iowa, Nevada, New Hampshire — and had so much to cover. The rallies, the crowds, questions, the eye contact, cheers, the emotion, the staffers on the sidelines. For readers, this kind of coverage breathes life into the campaign.

“We don't have that anymore,” says Thomas, who’s now working from home in Washington, D.C. “It’s hard to have that visual temperature we can take.” Coverage has gone from “seeing crowds from a pretty active campaign to suddenly you’re in your home on a Zoom conference call.”

For now, the path of the pandemic is the new campaign trail. With the race almost completely online, Zoom calls from Biden’s basement, where he has been broadcasting his campaign since late March, are the new norm. Thomas will get about four to five questions in during a press briefing, and there’s some back and forth, but the story is controlled by the width of the screen. To reach different demographics, Biden will host happy hours and family-oriented town halls online. But ultimately, it’s not the same as an ice cream shop.

For David Stebenne, a political historian at Ohio State University, no previous campaign has ever been quite like this. The 1918 Spanish flu offers little guidance as to what will unfold, as that was not a presidential election year. Instead, Stebenne looks to the 1968 and 1972 elections, when anti-Vietnam protests rocking the country posed such a threat to candidates that rallies to a large extent moved to in-studio televised town halls. “They may find some way to replicate that kind of model because they can't safely campaign in the conventional way,” he says.

It’s been a major adjustment for state reporters, too — only significantly more frantic. The terrain was a mess — voter ID laws, mail-in ballot laws, gerrymandering. Throw in a pandemic, and journalists are hustling to keep up as the election process gets caught in the fault lines of partisan politics.

Wisconsin will go down as the prime example.

As a regular swing state on the frontline of the presidential race, political upheaval is the status quo for the Journal Sentinel team, but the partisan chaos that unfolded amid the primary was extraordinary. After the Republican-controlled Legislature refused to postpone the election and the state supreme court overruled the Democratic governor’s postponement order, Wisconsinites had no choice: either head to the polls under stay-at-home orders amid a global pandemic — while all other states moved to delay their primaries that day — or sacrifice their vote.

In the wake of 11th-hour court rulings, hundreds of people flooded the inboxes of the team at the Journal Sentinel complaining about unfulfilled requests for an absentee ballot. Three large tubs of undelivered absentee ballots were discovered in a postal center outside Milwaukee. At least 9,000 ballots requested were never sent, and there’s still more data on missing ballots to come. The city of Milwaukee went from having 180 active polling stations to just five.

Political reporters are finding ways to report a story that is less about who is running than how the election runs and who gets counted

Between the absentee ballot processing backlog and poll closures, which fell particularly harshly on black voters, the episode raises serious questions about disenfranchisement and is viewed by some as an attempt at voter suppression. “Voter suppression is a loaded term,” says professor Edward Foley, director of the election law program at Ohio State University’s law school. But given its clear partisan motivation, “it does seem regrettably a reasonable inference.”

On April 27, health officials announced that at least 36 people who voted in person in the Wisconsin primary contracted Covid-19. Of the roughly 1.5 million voters, an estimated 413,000 voted in person.

When it comes to reporting on voter suppression, journalists need to be “really careful,” says Craig Gilbert, the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel’s Washington bureau chief, data whiz, and longtime political writer who has covered every presidential campaign since 1988. Even with the evident mess of the absentee ballots, appraising voter suppression is not straightforward. Because, well, how do you quantify it? “You’re writing about a negative, the votes that aren’t being cast,” says Gilbert, who did not use the term “voter suppression” while covering the primary “because it is so difficult to measure whether – and how many – voters who would have otherwise voted did not vote because of a particular requirement or restriction. It’s very hard to say with certainty that turnout was not as high as it could’ve been.”

In the case of Wisconsin’s primary, fears swirled that going ahead with the election amid a pandemic would suppress voter turnout, especially on the Democratic side. But the race ended up drawing a remarkably high turnout of about 1.5 million voters, which consisted of a spring election record of about 1.1 million absentee ballots.

To report as complete a picture as possible “in a world where the campaign is invisible,” journalists have to get creative and mine “every available source of information,” says Gilbert. Especially data. There are the traditional tools like historical election data and public opinion. But there are also timely metrics like data on absentee voting, down to the county and local level.

That’s what Gilbert used to decipher how Wisconsin’s absentee ballots made up such a large portion of the vote. Using an election database, Gilbert pinpointed clusters of communities with high absentee ballot rates. On Milwaukee’s North Shore in Whitefish Bay, 60% of registered voters sent in absentee ballots, more than any other city or village and higher than the 32% state average. Gilbert proceeded to find out that the towns, in light of the virus, had aggressively promoted mail-in voting and even took the extra step of printing up and mailing absentee ballot applications to about 10,000 registered voters.

This could offer some guidance on the viability of absentee ballots in November. In Whitefish Bay, the local government made voting more convenient by providing a reminder to request a ballot and by providing the request form itself. “If you think of barriers to voting or making the voting process cumbersome as ‘discouraging’ voting,” says Gilbert, “this is the opposite.”

But Gilbert is cautious about projecting the turnout for November using the outcome of the primary: “There’s just a lot of uncertainty. It just reinforces the fact that you have to be careful and a little humble about your ability to not just predict, but even measure what’s going on.”

Every election presents some kind of issue, says NPR reporter Pam Fessler who has been on the beat since 2000. That year was Gore vs. Bush. Over the years, there have been regular controversies over malfunctioning voter machines, long lines, and partisan fights over voter registration lists. In 2016, Russia interfered. But what’s happening now, “is very, very unnerving,” says Fessler. “Election officials — local, state, federal — have spent a lot of time preparing for potential problems in elections. One thing people did not prepare for: a pandemic.”

An important objective of ElectionLand: ensuring every newsroom stays on top of local election laws

After the confusion that unfolded in Wisconsin, calls are mounting to establish an all mail-in system by November, under the not unlikely scenario that the virus is circulating and a vaccine will not be ready.

While universal mail-in voting is not impossible and would reduce the risk of virus transmission, the administrative challenges are real. Currently, five states — including Republican-leaning Colorado and Utah — conduct elections by mail statewide. At least 21 others have provisions to allow at least some elections to be conducted entirely by mail, according to the National Conference for State Legislatures. But the transition takes time, foresight, political will, vigilance, and money — a tall order in a time of hemorrhaging state revenues. Ballots require reliable supply chains of paper. But not every voter has a mailing address, internet access, ability to print out a ballot, or money for postage. Sometimes a ballot requires a witness’s signature — how do you get that if you’re in isolation?

Yet the alternative of in-person voting carries its own potentially deadlier costs. On top of the health risk to voters, in-person voting largely depends on a volunteer base of poll workers, most of whom are elderly. If the virus is still circulating, that will shrink, along with the number of poll stations. Replacing elderly volunteers with younger ones without the knowledge and expertise could introduce a whole new set of issues.

“There is enough time to get this done so that November can be a free and fair, genuine opportunity to participate, even if we’re still in the middle of a pandemic,” says Foley, from Ohio State University. “But it has to be done. The good news is that failure is by no means guaranteed. But the bad news is, success is not either.”

For Aviva Shen, a senior editor at Slate, what happened in Wisconsin underscores the urgency of Slate’s latest election initiative, “Who Counts?” Launched in October 2019, “Who Counts?” is a project pursuing 2020 election coverage specifically tailored to voting, immigration, gerrymandering, and citizenship. After years of mounting issues, from voter purges to ID laws, Slate wanted to ensure voting rights remained a central focus in the 2020 election. The pandemic only brings that into sharper relief. “The pandemic has really shown a lot of strain in society in general, especially when it comes to elections,” says Shen. “This crisis is really exposing that there are huge structural problems and the stakes are even higher now.”

The coverage for “Who Counts?” focuses on mechanisms of power in elections and the communities they marginalize. Slate published a Marshall Project story on the possible disenfranchisement of some 470,000 inmates detained in city and county jails, where coronavirus restrictions could prevent civic groups from facilitating their paperwork. It ran analyses outlining the importance of the U.S. Postal Service in a functional election, and how voting rights advocates are shifting their focus to state courts. For a little fun, they also post puzzles: “Can You Put These Gerrymandered States Back Together?”

“Our readers recognize we’re in a crisis moment that these kinds of rights and norms that we’re used to taking for granted are not necessarily unbreakable,” says Shen. “There’s a lot of interest, not only what the problems are, but how do we fix this?”

Jessica Huseman, the lead reporter for ProPublica’s Electionland, won't report a federal-level claim about elections without verifying it with local districts. Citing everything from President Trump’s baseless claims about voter fraud to illegal ballots in California to false claims about mail-in voting favoring Democrats, “People need to ground their stories in what is actually happening at election administration offices rather than what the president or state officials are saying,” says Huseman. “Those two things are rarely ever the same.”

To ensure every county stays on the radar, ProPublica established ElectionLand, a coalition of over 120 newsrooms across the states that covers all things election-related: misinformation, cybersecurity, and any issues that prevent eligible voters from casting their ballots. Among the resources they share is a partnership with Lawyers’ Committee for Civil Rights Under Law, which transfers tens of thousands of calls from voters into a database of tips and complaints about voting issues. That way, reporters can quickly identify hot spots. Founded in 2016, the project has grown significantly.

Another important objective of ElectionLand: ensuring every newsroom stays on top of local election laws. American elections are a massive, decentralized enterprise with more than 10,000 independently-run voting jurisdictions. Compounded by a pandemic, the rules of the game are much more complex. Facts change quickly, and context is crucial. For Huseman, keeping readers informed underscores an essential but simple premise for election coverage: voting is good.

“We can talk all day long about journalism and bias and preconceived notions, but I think it's not wrong for journalists to decide that people should be able to vote,” says Huseman. “We live in a democracy ... If we start our jobs as covering elections from the twofold premise that people should be able to vote and we are participants in the elections, then our responsibilities become very clear:” make voting accessible.

For example, ElectionLand generally won’t write about lines longer than 30 minutes because studies show that lines up to half an hour do not discourage voters. Otherwise, you could deter people from going to the polls. It’s also crucial to report election laws accurately. Huseman recounts back in 2016 in Texas when voter ID laws were changing quickly and moving through the courts. The shifting information meant not everyone had the right materials and so couldn’t vote. “Lots of people don't read past the headline,” says Huseman. “We have to be really, really focused on the details because those little details, those are things that disenfranchise people.”

Election administration is technical, complex, and often eye-glazing. But for GPB Radio News’s Fowler, the coronavirus chaos is an opportunity to inform the electorate of how the process actually works through the people that make it work: poll workers.

Georgia is particularly convoluted. With 159 counties, Georgia has the second highest number of voting jurisdictions after Texas. That means 159 different sets of staff. Speaking to them as the gatekeepers is key. So Fowler and his colleagues spoke with more than half of the state’s county election directors for a radio story to illustrate just how complicated the process is, how much it impacts the lives of people dealing with the constant change, and how much it varies in every county. These are mostly elderly people, who are struggling to keep up with the day-to-day confusion of the pandemic.

The coronavirus chaos is an opportunity to inform the electorate of how the election administration process actually works

"Voting has inherently become a partisan issue, and I think the chaos wrought by coronavirus is only going to deepen that wound,” says Fowler. The human angle is key to depoliticizing it. “It’s more important for journalists to cover the mechanics of election administration and explain why and how decisions are made to deflate some of the rhetoric there is around accessing the ballots.”

The last few weeks have been a rollercoaster for Ashley Lopez, a reporter with NPR’s Austin-based KUT who covers politics and healthcare in Texas, which has some of the strictest voter laws in the country, when it comes to absentee ballots. So when the pandemic came along, fears mounted over whether people should be able to claim the “disability” category in order to obtain an absentee ballot based on a fear of catching the virus at the polls. After Texas Democrats filed a lawsuit to clarify who could seek mail-in ballots in the state, a county judge issued an order allowing any voter to apply for a mail-in ballot — trumping the state attorney general’s opinion to the contrary.

Now young voters are facing another major hurdle: registration.

Since the last presidential election, more than one million young people in Texas have registered to vote. Turnout for voters under 30 tripled in the 2018 Senate race. But the pandemic has stalled that momentum for one glaring reason: Texas is one of the few states that does not allow online voter registration, which is creating barriers for Texan youths, according to voting rights advocates Lopez interviewed.

To figure out how that demographic was coping, Lopez tapped into Texas voter groups she had previously covered and reported a story on how those groups are still endeavoring to mobilize voters digitally: calling, texting, and via social media. Groups are tracking down addresses of people and sending ballots and pre-paid postage so that all they have to do is fill out the ballot and pop it in the mail.

“We are talking about the same things that we were talking about before, but the stakes are so much higher now,” says Lopez. “I’ve been yelling about this for years, now everyone is like, ‘This is a real problem.’ This is why we have to deal with things years before a pandemic.”

An earlier version of this storydid not note that the story Slate published about the possible disenfranchisement of jail inmates was from the Marshall Project.