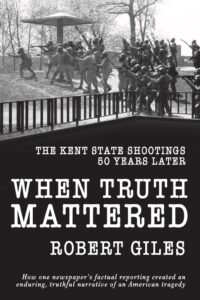

Robert Giles, former curator of the Nieman Foundation, was managing editor of the Akron (Ohio) Beacon Journal on May 4, 1970 when four students were killed at Kent State University during an anti-war protest. National Guard soldiers also wounded nine other people. The paper's coverage won a Pulitzer Prize for Spot News Reporting. In “When Truth Mattered: The Kent State Shootings 50 Years Later,” published today, Giles offers a gripping account of how he and his staff pursued the truth of the shootings during a time that the nation was sharply divided over the Vietnam War. An excerpt:

As noon approached on Monday, May 4, 1970, students were defiantly gathering on the Commons, the large grassy space at the crossroads of the Kent State University campus.

Among the number were an estimated 300 protesters and curious onlookers. The kids vastly outnumbered the faculty. It was easy to distinguish many of them by their long hair and casual, hippie attire.

The growing assembly was a signal that the rally on the Kent State Commons was going to go ahead, despite Ohio Gov. James Rhodes’ orders to the National Guard to use whatever force necessary to break up the protest.

Rhodes’ mandate was confusing to some but gave authorities little room for flexibility. When someone asked him for a definition of a protest, he replied “Two students walking together.”

For Jeff Sallot, May 4 was a special day. It was his last day of classes at the journalism school.

His days as a campus stringer for the Beacon Journal ended at dawn. By 11 a.m., he was on campus to begin work as a full-time BJ staffer.

Sallot hiked over toward a small group of uniformed men on the edge of the Commons. He found the National Guard brass huddled near the burned-out ROTC building. City police, university police and an officer from the Ohio Highway Patrol mingled with the military officers as they talked.

He didn’t see anyone from the university administration. This was a clear sign to him that the administration was no longer in the communications loop. His was a critical observation: Governor Rhodes had exerted his authority, and his instructions to ban the rally would be carried out.

Jeff walked into the Student Union and shoved coins into a pay phone. Pat Englehart, the state editor, came on the line in the Beacon Journal newsroom and asked for an update.

He told Pat he thought the rally would proceed peacefully. It would be out in the open, exposed by a bright sun shining on the broad expanse of the Commons. The previous nights’ demonstrations had been shrouded by the dark. Daylight would make a difference.

As 12:15 p.m. approached, Sallot calculated his deadline. It would be tight. He needed to make sure he could find a telephone that would enable him to give the newspaper a running account of the demonstration.

He knew Englehart would have his eye on the wall clock in the newsroom, making the same calculation as its minute hand crept toward deadline.

Sallot got to Taylor Hall, the journalism building, before the Guard moved out and began to chase people. Jeff knew the location by heart. Taylor Hall would offer the best vantage point overlooking the Commons. Time and a connection with Englehart were vital but so was satisfying his journalistic compulsion to observe. Taylor Hall would be his place to watch the action.

There were telephones in the J-school office. He raced down the corridor. The office was on the first floor as he came in from the Commons. He paused and then opened the door into the office of Dr. Murvin Perry, director of the J-school. He blurted a “hello” to Margaret Brown, Perry’s secretary.

He spotted a phone on a desk in front of a large picture window overlooking the Commons. Sallot asked Brown if he could use it. She nodded “yes.” “Can you keep the line open for me?” Again, she nodded “yes.”

Sallot reported his location to Englehart. He said it gave him a direct view of the confrontation developing on the Commons. He also told his editor the unbelievably good news that he had an open telephone line. “Good,” Pat said, “make damn sure you keep the line open.”

Sallot described a Guard Jeep pulling out to the center of the Commons and slowly moving along the lines of demonstrators. It carried two riflemen, a driver and a Kent State policeman shouting through a bullhorn that the rally was illegal under the Ohio Riot Act.

The students actively ignored the warnings. The noise and their number grew. A majority of the Guard began to march from one edge of the Commons toward the demonstrators gathering on the hill by the Victory Bell, a railroad relic that students rang after a football victory.

Sallot described the Guardsmen carrying M-1 rifles with bayonets, wearing gas masks and steel combat helmets. He said some of the Guardsmen were armed with tear gas grenade launchers.

Sallot was looking at a potentially combustible tableau. Tension was mounting as he fixed his eyes on the scene below. The Guardsmen were clearly outnumbered. The students were entirely outgunned.

The Guard began firing teargas canisters as it moved across the Commons and on up toward its crest. The teargas grenades arced through the air, leaving a trail of smoke that soon enveloped the scene. The sound from the grenades was a “pop” and then a hiss. A few students picked up canisters and threw them back at the Guard.

Smoke from the gas grenades created a weird and frighteningly smoky tableau that was dramatically captured in photographs.

The teargas was basically ineffective because a 14-mile-an-hour spring breeze blew most of it away from the demonstrators and back toward the burned-out ROTC building. It looked like a battleground.

Jeff’s hands were sweating as he held the phone. He looked down on the maneuver unfolding before him and described it to Pat Englehart in the newsroom in Akron.

Taylor Hall’s ventilation system started sucking in the teargas. Sallot would later recall: “Ms. Brown, God bless her, crouched under her desk away from the window,” still clutching the phone and its critical connection from Jeff to the Beacon Journal. This selfless act provided the link by which truth found its way to the outside world.

Tension was palpable in the newsroom. Several of us were gathered around the state desk listening to Pat Englehart shouting instructions to his young reporter. Jeff insisted that he needed to go back outside. Englehart forbid him to leave the phone. Sallot turned to Margaret Brown, who assured him she would indeed hold the open line for him.

Sallot told Englehart that the protesters were keeping “a safe distance” in front of the advancing Guard.

The crowd, students and soldiers, swarmed past Taylor Hall. He could see the Guard split and go around Taylor Hall from both ends. Students and the Guard units moved beyond Sallot’s line of sight from the J-School office window. He handed the phone back to Brown and ran to a Taylor Hall exit near the veranda.

From there he could see the Guardsmen headed back up Blanket Hill toward an umbrella-shaped Pagoda, which stood at the crest of the hill.

Another brief lull in the commotion gave Jeff the idea that the Guard had completed its mission. Maybe the rally was over. He guessed that most people would begin to wander off to lunch or afternoon classes.

He had to alert his editor that the Guard seemed to be standing down and moving back toward its bivouac area near the ROTC building. He headed back to reclaim the telephone in Taylor Hall.

He had reached the veranda at the front of the building when he heard gunfire. In an eyewitness account for the Beacon Journal, he wrote, “Some people say there was a single shot followed by a volley. It seemed like just one volley to me.”

Jeff looked to his left and saw that the Guardsmen next to the Pagoda had turned and fired. Rifles seemed pointed in several directions, and he could see that he was in an exposed position.

“Some people thought these shots were blanks being fired. I knew this was live fire when I saw a clump of dirt near me puff up where a shot hit the ground.” He dove for safety, moving out of the arc of fire.

Sallot saw that he was just a few yards away from a student who was shot in the back. (This was Bill Schroeder.)

Jeff scrambled back into Taylor Hall to the J-school office It was a few minutes past 12:30 p.m. Brown, trembling, handed him the receiver with its open line to Englehart.

Jeff breathlessly shouted into the phone, “The Guard fired! They fired! They fired right in front of me. Some people were hit. One guy looks dead. He was hit in the head.” (This was Jeffrey Miller.)

Englehart yelled all of this to the newsroom.

Minutes later, a bell on The Associated Press wire machine began to sound its “ding, ding, ding, ding, ding” announcing that a news FLASH was moving. “Shots fired at Kent State.” The AP story offered no other details.

The newsroom exploded into action. Details trickled in at first.

I ordered the news desk to hold the press start for the home edition. It was a moment that came close to fulfilling an editor’s dream of shouting, “Stop the Press!!”

We had an eyewitness to tragedy. I was now certain there were casualties, maybe dead students.

I knew what the moment demanded. Don’t rush into print until you are certain you have the best available version of the truth. Then go with it.

Unlike an assassination or a war or a mass murder in a far-off city, this story was ours. On a warm spring day here in Ohio. In a college town next door.

Guardsmen shot at kids, Sallot told Pat Englehart. Bodies down. No names. Confusion. The campus seemed to explode in pandemonium.

Minutes after the horrific sound of rifle volleys, then screams for help, a reporter from United Press International began to dictate from a phone in the National Guard command post.

From that spot, he was able to listen to the National Guard radio over a Portage County sheriff’s department frequency. He heard one officer call out for ambulances, “We’ve got two dead up here.”

The UPI journalist assumed this meant two dead Guardsmen. And that is what he filed. His competitive heart beat fast. His first priority on a big, breaking story demanded this: don’t let the AP be first.

His dispatch went to the UPI news bureau in Cleveland. Through a series of phone calls linking the UPI Columbus bureau and then the University News Bureau, the wire service confirmed that, “Yes, there were two Guardsmen killed.”

Within minutes, UPI moved a bulletin with the erroneous report of the fatalities on the Kent State campus.

AP’s bulletin said the dead were four students. Englehart clutched the UPI story as he asked Sallot several times if he was absolutely certain there were no Guardsmen down, just students. Jeff said he thought so. At that moment it crossed the young reporter’s mind that, “if I am wrong, this might be the end of my newspaper career.”

Beacon Journal editors were scrambling to put together as compete a story as possible, and the production manager was yelling that he needed to start the presses.

Tension was at the breaking point as we faced a critical choice: Go with the UPI story from an experienced reporter that two Guardsmen were among the dead. Or trust Jeff Sallot, our own reporter on the scene, who was telling us the four dead were students.

Englehart turned to me. “What should we do?”

“Let’s go with Jeff,” I ordered, almost without hesitation.

For what seemed an eternity, competing versions of reality were alive in the outside world. Sallot’s report that four Kent State students were shot and killed by Ohio National Guardsmen was being distributed on The Associated Press wire.

And the UPI story reporting two guardsmen and two students being killed in an anti-war demonstration was being quickly edited on news desks in small newspapers and radio stations around Ohio.

Station managers interrupted scheduled programming to broadcast bulletins with the erroneous report. Someone on the BJ state desk yelled across the newsroom that radio stations were going with the UPI story.

I knew that if this error wasn’t soon corrected, many Ohioans and listeners across the country would come to believe as true earlier rumors that snipers were on the campus and radicals were to blame for this serious trouble.

The importance of Sallot’s ability to secure an open phone line soon became apparent. We learned later how critical it was. That afternoon, he had the only working phone line out of Kent State as the dead and wounded were evacuated and students cleared the campus that had been ordered closed.

A terrible tragedy had erupted just beyond Margaret Brown’s office window in the J-school. She was Jeff’s steadfast ally in keeping the phone line open for him to send his urgent and truthful minute-by-minute reports from campus.

On May 4, 1970, truth mattered, and it still does.

Excerpted from “When Truth Mattered: The Kent State Shootings 50 Years Later” by Robert Giles (Mission Point Press, 2020). Reprinted with permission.