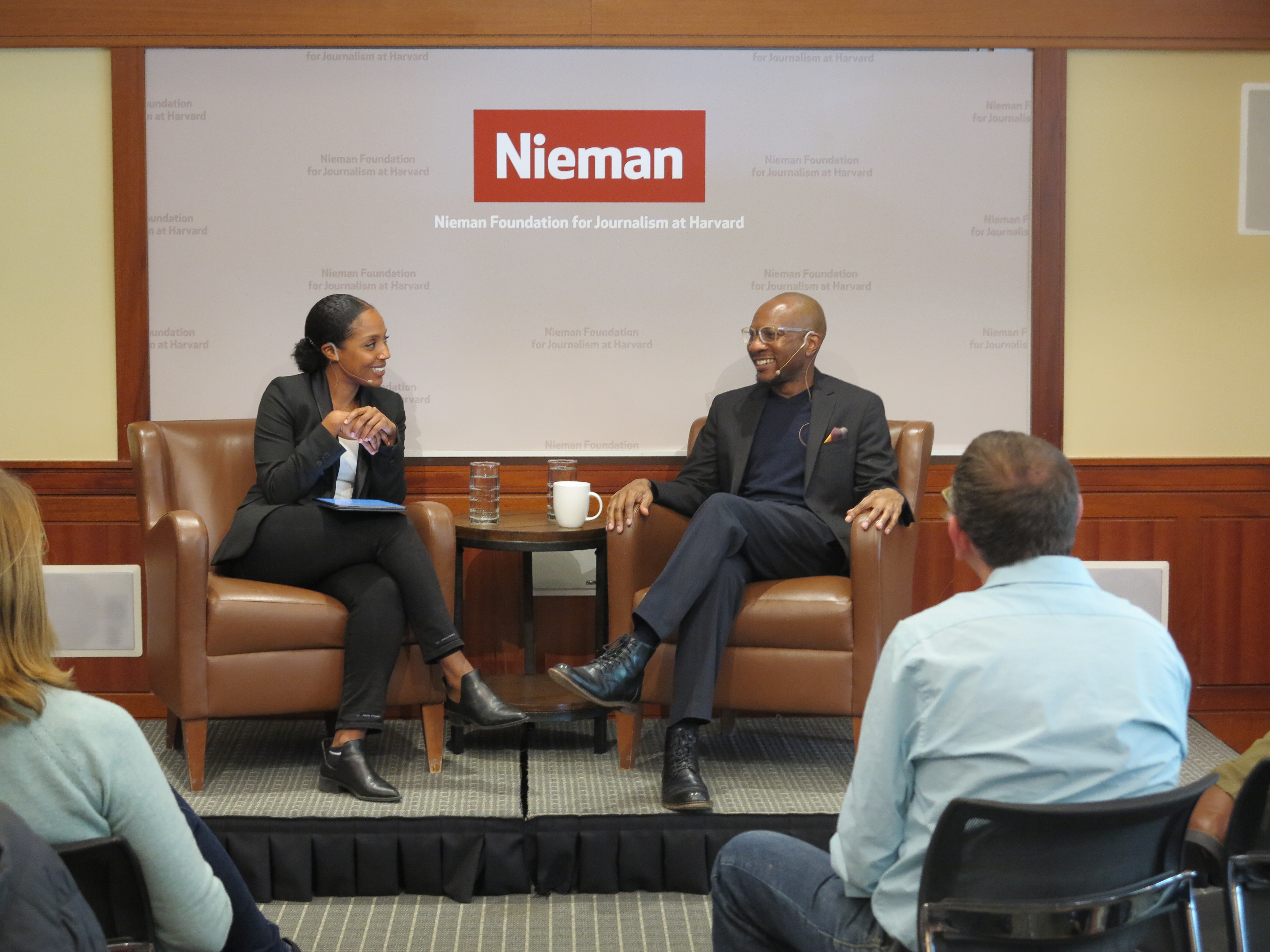

From 2015 to earlier this year, Cole wrote a photography column for The New York Times Magazine. He is the author of the novel “Open City,” the essay collection “Known and Strange Things,” and “Blind Spot,” a work of photography and texts. He’s working on a nonfiction book about Lagos. Born in the U.S. to Nigerian parents, he grew up in Lagos, the largest black city in the world. When he spoke at the Nieman Foundation in October, he called Lagos “the place where the culture is being made.” Now a Cambridge resident, Cole is the Gore Vidal Professor of the Practice of Creative Writing at Harvard. Edited excerpts:

On pushing boundaries

With great freedom comes great responsibility to freedom. In other words, regardless of your career path, you’re freer than you think you are. A lot of people have the habit of hedging and thinking they are less free than they actually are, but you just have to push a little bit, both in terms of content and the stories you pursue, but also in terms of form.

For example, in my experience of writing for The New Yorker and The New York Times, a lot of times the question has been, “What can I get away with?” Part of the answer to that is, understanding the good relationship I have with my editor, and with my editor-in-chief, and getting a sense with each subsequent piece of how much I can push.

On images of “otherness”

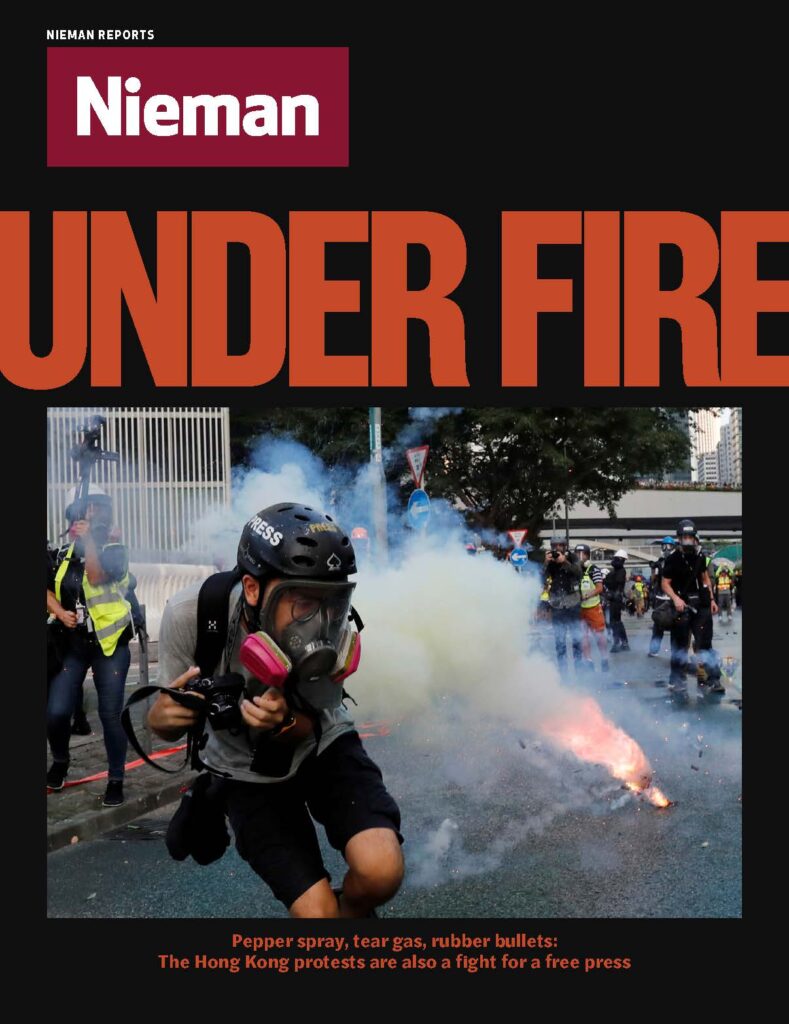

The people who win Pulitzer prizes for photojournalism, it’s usually for some kind of violent image on the front page of The Washington Post or The New York Times, and the justification is always the same: we need to know the news, and, oh, those terrible pictures can help move policy, because people see how terrible things are.

There’s actually no evidence for that. If you look at this stuff closely, what there does seem to be evidence for is that the kinds of violent images that are shown tend to be violent images of things done to certain bodies. Much, much easier to show injured or destroyed black bodies, brown bodies, foreign bodies, than a white, middle‑class American body.

Now I’m not saying that violent images make no difference. I’m saying the relationship between the portrayal of violent bodies and policy is not automatic. In fact the images that make a difference are very much the exception rather than the rule. The rule does tend to be that we’re able to absorb other people’s suffering much more easily than we can absorb the suffering of people we identify as being “like us.”

At the time that that photo of Óscar Alberto Martínez Ramírez and his daughter Valeria, both of whom died on the border, was presented, everybody again said the exact same thing, which was, “Well, maybe it’ll change things on the border. Maybe we’ll be shocked into some change.”

That was in the summer. What has changed? Absolutely nothing. What has changed is that we all consumed the image and we developed even more scar tissue and absorbed it into “what happens.” I would venture to say few people even remember their names. In “A Crime Scene at the Border,” I argued that we’re not able to read such images properly, because we read them as newsworthy, we read them as occasions for a performance of empathy, which is necessarily brief, rather than reading them as evidence of crime, crimes committed by us in the collective.

The real problem is when you think the news is that Óscar or Valeria drowned; but that’s not the news. The news is that we instituted metering at the border so that people can be in limbo, in a nightmare of suffering, in heat and endless waiting. How do we push that to the front page every day and say, “This is a human rights violation, this is unspeakable?”

I cannot narrow it down to “If we didn’t publish it, The Washington Post would publish it.” The whole frame is just wrong. I know it’s very hard to turn a massive ship around, but I would at least like to ask that question. If that whole ship was turned around and that image existed inside a context, that would be one thing.

I remember having a difficult and not completely comfortable conversation with my editors at The New York Times Magazine about a story that had nothing to do with my writing. They had a picture of a starving child from Yemen on the cover. It was done with the usual reasoning: to excite the conscience and all of that. Meanwhile, Yemen goes on. This was last year, but Yemen continues.

I made the argument that they would not show a white kid from Indiana who was dying from some terrible illness in this way. They believe that they bring the facts, that with this picture they are showing what the Saudis are doing. But unless, in a persistent way, we are indicting the whole American apparatus of statecraft, that picture is useless. Unless we actually have clear, principled, and persistent opposition to the forms of agreements among American allies that are leading to this kind of suffering, the picture is merely pornographic.

It doesn’t merely come down to whether we run the image or not. It comes down to looking at something like CNN and saying, “Who decides that that’s news?” The melodrama they present is not the news. The news is everything that has led up to it.

On not reporting stories in a neutral way

I read this morning in the Times of a suicide bomber in Afghanistan in a rural place. Explosives had been packed inside a mosque, the roof had collapsed, and 60 people had died. Thousands have died this year because of political instability there.

This story was typical, and fact‑checked, I’m sure, according to New York Times standards. Yet for me, it was again an occasion to say, what is this story? There is no context for thinking about what this is. Of course, there was that line, “It could not be determined right away who had done this.” Well, part of the ideological function of such a story is that it’s crazy over there. Almost as if crazy things happen over there for no good reason.

I don’t think it’s responsible to report such a story in an allegedly neutral way. Any such story must be reported with a reiteration of what is true about why somebody’s blowing himself up at a mosque in Afghanistan, which is that we have everything to do with it. How do you convey that in every single iteration of every such story?

They’re not crazy people. They don’t want to die. The people who were killed didn’t want to die, the guy who blew himself up maybe wants to die but there might be reasons for it. If 60 people died in Cambridge, Massachusetts for whatever reason, we would experience it as an unbearable and profound human story.

If we’ve othered Afghanistan to the extent that I can just read this over my breakfast and think, “Uh, that's a pity,” then it’s a problem both for journalism and for photojournalism. The near impossibility of telling the true story is that everything we’re reporting on is something we’re involved with and our involvement is usually not innocent.

This very much stops being a question about journalism and becomes a more complicated question: what constitutes the contemporary “we” and what are the nodes of responsibility that encircle that “we”? A “we” which always, of course, presumes itself to be innocent, distant, unconcerned, neutral, and objective—though none of those things are actually true.

On asking “What if that was us?”

In all possible ways, people have to commit themselves to siding with life and human dignity. Finding a way of asking the question, “What if that was us?” Especially at the newspapers and magazines we write for, and at big powerful institutions like Harvard.

We can get very mentally theoretical and say, “Well, the Indian government might be overreaching but the Kashmiri should also behave themselves.” We have to get to the point where we say if one or two people are wounded on one side and 24 people are killed on the other, there’s no room for gray there. That’s not when to call on both sides to show restraint. Somebody always says, “I’d call on both parties to show restraint here.” This false equivalence is happening all the time, and I think we’re losing our souls if we participate in that.