I went into journalism because it’s like a box of chocolates. If you know what you’re going to get, that takes all the fun out of it.

I got myself to Afghanistan in 2010 with frequent flier miles, a few hundred dollars cash from my day job, and permission, the only one ever granted, to embed with the contingent of Drug and Enforcement Administration (DEA) agents in the war zone. The DEA had quietly surged from six to about 100 personnel on a mission from the White House to reduce the flow of Afghan heroin dollars to the Taliban.

I had a straightforward plan—research and write a book about the new kings of heroin. Nobody had even printed their names, but I’d done enough reporting to come up with a short list. These South Asian gazillionaires were a bunch of dusty Fourth Century tribesmen riding horses, donkeys, and camels and wielding satellite phones. They were nowhere as sexy and murderous as Colombian and Mexican drug lords I’d profiled for Time and Newsweek and my 1988 book, “Desperados,” but their money fed the quagmire. Agents called them “unarrestables,” due to their influence with the Afghan power elite and usefulness to coalition forces.

The American people deserved to know all this, but no publisher was eager for a narrative with so little forward motion. I yearned to write a story with a beginning, middle, and kickass endgame. In Afghanistan, one or two investigations were coming along slowly. Meantime, I decided to look elsewhere for a chocolate-covered cherry.

I swerved onto the offramp. Cocaine, heroin, and Mexican meth were flooding across Africa on the way to Europe and the Middle East. Millions of dirty dollars were flowing into the coffers of organized crime and Islamist militants like Hezbollah, Al Qaeda in Africa, Boko Haram, and Al Shabab. I got into the DEA Special Operations Division and found investigators specializing in trafficking in Africa, Middle East, and Asia. I turned holidays in Istanbul and Paris—stops on the old but still vital French Connection—into work trips.

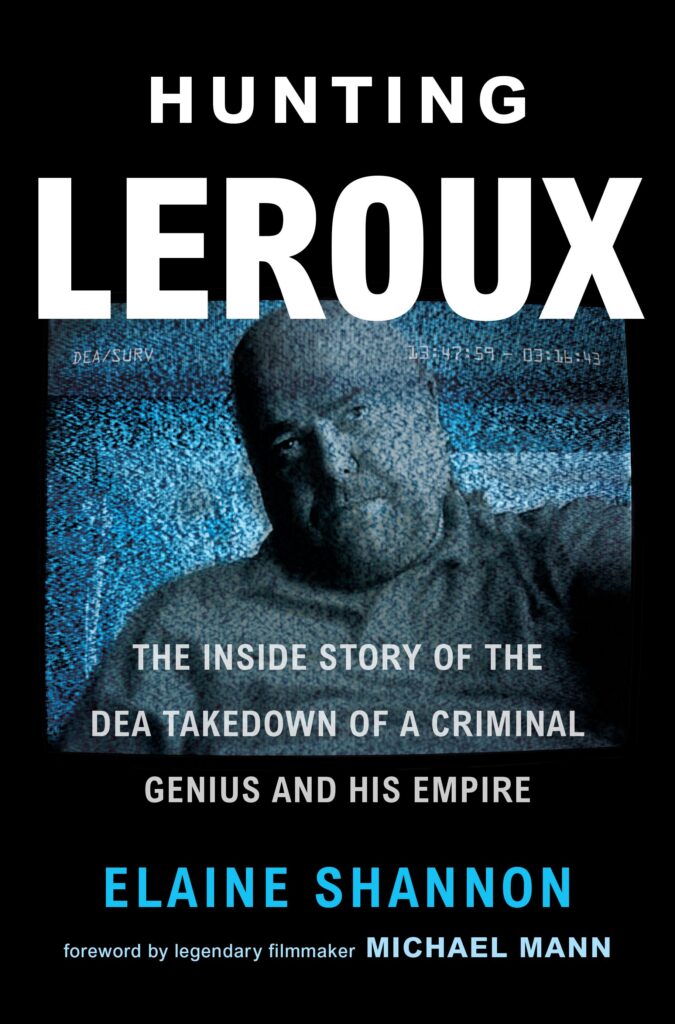

One day in 2013, an agent I’d met in my travels told me about a new kind of organized crime leader: brilliant, powerful, with no morals and no conscience. “He’s like the guy in the James Bond movies, always at his computer,” my friend said.

That’s all I needed to hear. I started following the tortuous trail of Paul Calder LeRoux. It took me five and a half more years, but “Hunting LeRoux,” published last month, is exactly what I was after—a chance to explore a marvelously complicated criminal mind and the equally complex brains of a small band of superb criminal investigators. Changing plans, staying loose, and following my gut won me every damn chocolate in the box.