I was born in Charleston, South Carolina, the city where the Civil War began and attended a school system still segregated and underfunded nearly half a century after Brown v. Board of Education, a system that didn’t know quite how to handle students like me.

Nearly everyone in my high school received free or reduced lunch. I received free lunch and food stamps and big, rectangular boxes of government cheese.

By the time I reached college, I couldn’t count all the days of ridicule I had experienced in class and in the hallways and on the playground because I was different. Every day, I had been underestimated and overlooked for something over which I had little control, something which shaped my life like nothing else. At private, elite Davidson College, I knew no one would understand what I had experienced in my young life. There wouldn’t be enough people like me around.

Things got no better after I had secured a degree and had been recognized for my writing and thinking abilities. That’s why I walked into interviews thinking it unlikely I’d land a job—and walked out knowing my initial fears had been realized. The process repeated itself multiple times. My credentials and talent and potential didn’t matter.

Though I’m two decades into my journalism career, little has changed on that front. In an industry struggling with a decades-long lack of diversity, I’m still facing the same barriers I faced when I was a young boy because my chosen profession employs too few people like me, too few people who understand the challenges I face.

Yes, I am a black man who grew up in a racist South and work in an industry with a horrific track record on racial diversity. Your brain has probably conjured images of potential employers, probably a white man, not a woman, because “employer” and “white man” so easily go together.

But I’m not referring to my difficulties dealing with race, but rather with a nearly-lifelong struggle with a severe stutter that has cost me more professional opportunities than the color of my skin. It is the first thing I wake up to every morning, wondering how I will cope throughout that day. My race matters—it can’t not matter where I live—and it remains near top of mind as well. But it does not shape my daily perspectives and mood nearly as much as my stutter.

Having to contend with how others responded to my stutter taught me that people’s brains run on autopilot more than they like to admit

That’s how I first came to understand the concept of implicit bias, long before I knew researchers had coined the term and tried to measure it. Having to contend with how others responded to my stutter taught me that people’s brains run on autopilot more than they like to admit. I relied upon that knowledge to conduct race relations courses I designed, telling participants to close their eyes and report the image that automatically popped into their heads when I uttered words like “criminal” and “drug dealer.” Most of them would sheepishly reply they imagined a black man.

That’s implicit bias at work.

While research into implicit bias is still developing, what we know now has important implications for journalism. A commitment to grappling with implicit bias could become an effective way to help the industry produce news coverage that more accurately depicts an increasingly diverse world, transform audience engagement and increase trust, and identify and overcome unspoken and unrealized internal divisions that negatively affect relationships within newsrooms.

Implicit bias refers to an automatic or unconscious tendency to associate particular characteristics with particular groups. It is not malicious but could lead to disparate treatment of individuals and groups. The phenomenon was illustrated in orchestra auditions. Until the 1970s, orchestras were only 5 percent female, even though those conducting the auditions were convinced they were choosing candidates based solely on the quality of their play. Then most major orchestras began doing something called “blind” auditions, in which a screen concealed the identity of the musician, allowing the jury to judge only the music being played without unwittingly being influenced by gender.

According to “Orchestrating Impartiality: The Impact of ‘Blind’ Auditions on Female Musicians” by Claudia Goldin and Cecilia Rouse, “using a screen to conceal candidates from the jury during preliminary auditions increased the likelihood that a female musician would advance to the next round by 11 percentage points. During the final round, ‘blind’ auditions increased the likelihood of female musicians being selected by 30 percent.”

Disparate treatment also shows up in job applications with black-sounding and white-sounding names on résumés that are otherwise identical, on dating sites, and in choices people make on Airbnb. It’s been detected in housing decisions that have led to increased segregation.

Implicit bias has also been found when human beings create technology to do the judging impartially. Software engineer Jacky Alciné discovered that Google Photos was classifying his black friends as “gorillas.” It’s a problem Google has acknowledged will take time to fully contend with, which is why it blocked its algorithm from recognizing gorillas, and at least for a time racial terms such as “black man” or “black woman.”

Journalism has not been immune to the phenomenon, with research showing that female politicians are treated differently in news stories, and by voters, from male politicians, while black families are overly associated with crime and Muslims with terrorism by media outlets convinced they treat every group fairly. Studies such as one in Political Research Quarterly have found that stories in which the candidates running are only women, the focus is more often about character traits and less often about issues. Researchers at the University of Alabama found that terror attacks committed by Muslims received 357 percent more coverage than attacks committed by others.

The bias blind spots in our thinking are largely the result of how the brain processes the flood of information it constantly receives. We receive billions of bits of information every day, most of which we can’t consciously process. The brain sorts through what we need to focus on, often prioritizing things that will ensure our survival. That’s why we can be startled by a sudden, unknown sound or a shadow that shows up unexpectedly in our periphery. It doesn’t matter that it’s unlikely to be a bear or a ghost; our brains automatically cause us to respond as though it might be, just in case. Live in an environment long enough and such associations can lead to automatic, misleading responses.

Because we live in an environment that includes centuries-deep stereotypes about groups, it also seeds the ground for negative associations that affect how we view others. When you live in an environment that repeatedly reinforces the idea that “criminal” and “black man” is the norm, the brain has a tough time making you comfortable with dissimilar pairings.

While research into implicit bias is still developing, what we know now has important implications for journalism

The growing recognition of implicit bias is happening as the U.S. undergoes profound demographic shifts and as technological and other advances make it possible for the formerly-unheard to be heard. In homogenous groups, in which everyone believes and shares the same values and outlook and experiences, implicit bias can seemingly lay dormant. The effects of implicit bias become more noticeable when a well-established order, no matter if it was good for a few and bad for the majority, is challenged. Today, seemingly everything is being challenged.

White evangelical Christians believe they see implicit bias, or even intentional animus, at work in how mainstream media depict them.

Liberals believe they see implicit bias because journalists and media outlets have become so concerned about cries of “liberal bias” from conservatives they’ve slanted coverage to avoid that label.

Native Americans suffer from a host of disparities on a variety of issues, as much as African Americans, but are often left out of discussions and media coverage.

Asian-Americans and Latinos feel the same about their portrayal in media.

Women feel the sting of limiting gender stereotypes in print, online, and on the air.

Journalists of color know the dismal statistics about their representation in most newsrooms in the United States.

A growing number of white men feel put upon for being white and straight.

Then there are the disabled and mentally ill, who often feel excluded.

What about police officers who feel unfairly attacked by media because of the focus on statistically-rare police shootings?

Gays and lesbians and bisexuals and the transgendered and Muslims and Arabs and the overweight—the list is long—are among others who feel aggrieved.

For journalists, correcting for implicit bias can be a way to account for gaps in our knowledge and perspective that might be undermining our work in ways of which we are unaware.

Take my stutter, for example. I know most people are aware of stuttering but believe they understand it better than they do. They probably rarely encounter severe stuttering, forcing their brains to rely upon incomplete and often distorted information even as they try to make sense of what they are encountering.

That’s why bullies and non-bullies have initially laughed when hearing me speak. The bullies did so explicitly, purposefully, to belittle me. Non-bullies, including family members and friends, have done so reflexively—as though they couldn’t help it—because my stutter made them uncomfortable.

Each of them viewed me the way a gaggle of producers at broadcast outlets—NPR, MSNBC, CNN and NewsOne among them—have since come to see me. They don’t use the words “too dumb to talk,” like the kids who taunted me on the playground, while rescinding offers to appear on air. But the result has been the same: a broad-based silencing by a media infrastructure built, maybe unwittingly, to nearly almost always exclude voices that don’t sound quite … right.

A similar process may be at play in the minds of readers, listeners, and viewers as they process a journalist’s work, answering unanswered questions based on their own experiences and interpreting a report based on the context provided. Take, for example, a tweet by The Wall Street Journal about the 2017 Wimbledon tennis championships: “Something’s not white! At Wimbledon, a player failed his pre-match undergarment check.” The tweet accompanied a photo of Venus Williams, a high-profile black player who, along with her sister Serena, helped redefine the sport over the past two decades.

Implicit bias has also been found when human beings create technology to do the judging impartially

Readers could have understood the tweet as a light-hearted attempt to discuss Wimbledon’s all-white garments policy. Including the photo of Venus Williams was a reasonable journalistic decision. But a better choice would have been a photo of the white 18-year-old male player referenced in the tweet, or a differently-worded tweet. Williams was doing unexpectedly well in a major tournament late in her career and a week earlier had to change out of a pink bra that violated the all-white policy. That’s why choosing her photo seemingly made sense. It provided important context.

That’s not all it did. Many readers viewed the tweet as a not-so-subtle jab at Williams’s skin color. While the journalists who pulled together the tweet, story, and photo had reason to believe they had checked all the appropriate journalistic boxes, they neither accounted for implicit bias—their blind spots, or their audience’s—nor appreciated the still potent issue of race.

Those journalists could have earnestly believed writing “something’s not white” over the photo of a black player had nothing to do with race. That’s how implicit bias works. It’s not malicious, but it can blind you to other people’s realities. For many Venus Williams fans, there is no escaping the import of race. She isn’t well known only because she’s a great player, but because she’s a great black player in a sport that had long felt off-limits to black people. In less than an hour, The Wall Street Journal had deleted the tweet and apologized.

Another example of this phenomenon is the intense reaction to a New York Times article about Michael Brown, whose shooting death at the hands of a police officer in Ferguson, Missouri, led to explosive protests. Brown was said to be “no angel.” On the surface, it was just another benign descriptor that parents across the globe have used to sometimes playfully refer to their own children. The intent of the journalist John Eligon was likely a sincere attempt to describe Brown’s past run-ins with authority and a much-discussed strong-arm robbery as part of a fuller picture of the complex life the teenager had lived. Eligon told Times public editor Margaret Sullivan that in proposing a profile of Brown he wanted to tell the story of a young man who “despite his challenges and obstacles, was someone who was making it.” Brown had graduated from high school on time and was planning to attend college.

In the context of the emotional issue of questionable police shootings, to many readers, it signaled something sinister. Young black men are “no angels” even when they are on the receiving end of bullets. It suggests there is an inherent link between criminality and blackness, particularly given that such descriptors have rarely been used for young white men, such as Dylann Roof, who have committed massacres in churches, movie theaters, and schools.

A journalist who fails to recognize she has blind spots can unintentionally distort the meaning of her reporting. Not understanding the country’s racial history can unwittingly convince even the best journalists to write about minority groups in ways that can lead to harmful racial stereotypes—or exclude them from coverage all together. That’s why implicit bias researchers are more concerned with providing journalists with tools to help them recognize their biases than expecting training to automatically lead to changed behavior.

“Implicit bias became a popular topic a few years ago, but the election of Donald Trump as president really accelerated journalism organizations’ fervor to be as accurate as possible,” says Tonya Mosley, the senior Silicon Valley editor for KQED in the San Francisco Bay Area who helped create an interactive implicit bias workshop for journalists while a Stanford University Knight Fellow. “We don’t think ‘bias training’ offers some magic solution, but a real discussion about how our work is impacted is valuable.”

The bias blind spots in our thinking are largely the result of how the brain processes the flood of information it constantly receives

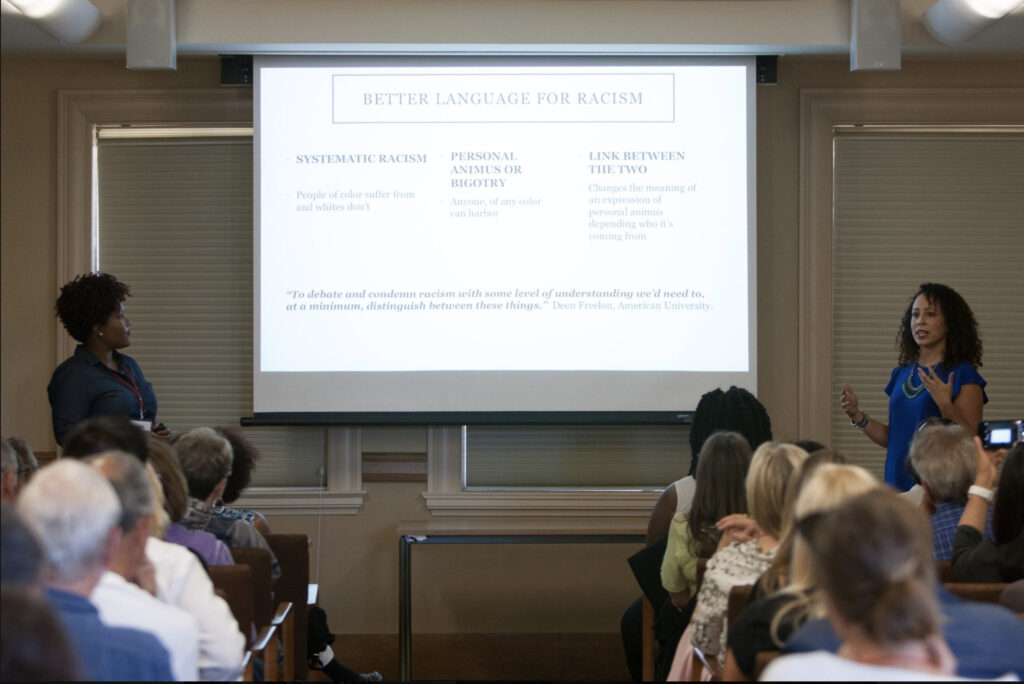

Mosley, along with Knight Fellow Jenée Desmond-Harris, conducts workshops designed to help journalists think about their individual work and their approaches. Journalists are asked to reflect on their upbringing and how their “interactions and world views creep into their approaches to journalism.” Often, journalists “just want to talk freely about the challenges they are dealing with. This shows us that there is a want, a need to talk through one of the main tenets of journalism—and that is objectivity,” Mosley says.

The workshops are not an easy fix, but neither were sexual harassment and cultural competency trainings, says Mosley. One of the most powerful tools in her toolkit is the self-audit, an objective examination of one’s own work. Are almost all your sources white men? Is your work devoid of voices that don’t neatly fit into a number of “traditional” categories? If so, ask yourself why. Is it because there are no credible voices on your beat outside of the traditional ones? Or is it because your source list was built upon a foundation of traditional voices who most frequently recommend other traditional voices for inclusion in your stories?

Sometimes, the best voice for a particular story will be a straight white man. The self-audit, though, forces the journalist to stop and think, to reconsider how her source list was built and is being used on a daily basis.

Maybe non-traditional voices are available and can deepen your stories but will take an extra call or two to identify, contact, and include. If implicit bias is essentially having our thinking on auto pilot, the self-audit is the journalist re-taking the wheel.

A journalist can use such a periodic assessment to determine if they are reliant upon a particular kind of voice, while unwittingly ignoring others.

“It takes daily practice by individuals and a company/organizational commitment for there to be a true cultural shift. We talk at length about journalists building a toolkit, and using those tools on a daily basis, sometimes story by story,” Mosley says. “We ask journalists to reflect deeply and examine how their own upbringings, interactions, and world views creep into their approaches to journalism.”

Virtual reality may be part of the solution to the implicit bias conundrum by allowing people to do the seemingly impossible: have firsthand experience about what it feels like to live in another person’s skin. As Joshua Rothman of The New Yorker reported, researchers have found that “inhabiting a new virtual body can produce meaningful psychological shifts.”

In one study, white participants spend around 10 minutes in the body of a virtual black person, learning tai chi. Afterward, their scores on a test designed to reveal unconscious racial bias shift significantly. “These effects happen fast, and seem to last,” one of the researchers told Rothman. A week later, the researchers found that white participants still had less racist attitudes.

Implicit bias isn’t malicious, but it can blind you to other people’s realities

While virtual reality and other efforts have shown promise, there is no guaranteed solution to correcting for implicit bias in news coverage. Mosley and others have said training efforts can even backfire if not well-designed, creating resentment and obstinance.

But there are several things outlets can do to lessen the likelihood implicit bias will influence their work. Innovative thinking aimed at reforming the criminal justice system speaks to the challenges and potential of such efforts.

Adam Benforado, a law professor at Drexel University, tackled implicit bias in “Unfair: The New Science of Criminal Injustice,” a detailed look at cognitive processes—not impartiality, racist malice, or a nuanced understanding of evidence—and how they affect seemingly-benign factors, such as “the camera angle of a defendant’s taped confession, the number of photos in a mug shot book, or a simple word choice during a cross-examination,” which in turn help determine guilt or innocence in court cases.

Researchers have found that jurors are more likely to believe the suspect is making a voluntary statement when the camera is focused on the suspect. When the camera is positioned to show the interrogator and suspect in profile, “the bias toward believing that the suspect is making a willing statement is removed.” It affects every level of the system, from the cop on the beat to the juror in the jury box and the judge presiding over it all.

Benforado has proposed a radical solution to a radical problem, which amounts to, among other things, creating a kind of veil for courtrooms to do to criminal justice what blind auditions did for elite orchestras. He wants to eliminate as many factors as possible that might trigger a person’s implicit bias. No more telling jurors to consider the defendant’s body language or allowing them to even know the race of the defendant. The goal is to remove the possibility that jurors, judges, prosecutors, and police officers will unwittingly rely upon implicit-bias triggering factors to make what should be impartial decisions. The system may need to move to a kind of virtual courtroom so judges and jurors can’t be influenced by a witness’s attractiveness, a defendant’s skin color, or a prosecutor’s body language, Benforado wrote.

He knows journalism can’t adopt the same reforms but believes three changes can make a substantial difference now: Remove racial identifiers from résumés, adopt a blind résumé review, and stop using personal connections and word-of-mouth to make hires, practices that are sure to reproduce the kinds of staffs that have always been produced.

“Really trying to make newsrooms more diverse is really, really critical,” Benforado says. “We are all biased, but people are biased in different ways. You don’t want everyone with the same perspectives. Eventually you will bring someone in for an interview, so think of ways to tie your hands a little more to focus on the metrics you are looking for and less on the intangibles, such as thinking they ‘feel right’ or ‘fit’ our culture. Any unconscious biases could come in there.”

A journalist who fails to recognize she has blind spots can unintentionally distort the meaning of her reporting

Hiring reform is only part of the solution. Internal practices must also change. Newsrooms should begin aggregating data about their coverage decisions, including tracking how many stories are told about a particular area, who is usually included in the stories as sources, among other things, and study it. “If you are working as part of a team, have an outside person review it with racial cues removed to look for problems,” Benforado says. “It’s possible that in interviewing white people versus black people, the same journalist might be asking different questions but think they are asking the same question. How many stories are about white wealthy people? Poor black people? It could tell you there is a problem, whether it is implicit or explicit.”

It might not be possible to pinpoint how implicit bias influenced an individual story or hiring decision, but these kinds of tests can force newsrooms to not only think anew, but to implement strategies and procedures that lessen the likelihood implicit bias will keep quietly shaping coverage and hiring patterns. The Post and Courier in Charleston, South Carolina, has had discussions about the implications of implicit bias, though it hasn’t done testing or comprehensive training on the subject. Its newsroom is not diverse. But covering racially-charged news events has forced it to grapple with the issue in ways it had not previously.

In June 2015, a young white supremacist named Dylann Roof killed nine black people during a Bible study at one of the nation’s longest-standing black churches. Just a couple of months earlier, a white North Charleston police officer was caught on video shooting a black man who had his back to the officer. The newspaper’s coverage area includes the place where the first shots of the Civil War were fired in a state where the Confederate flag flew at the State House for more than half a century.

“We talked a lot among ourselves, and we sought advice and feedback from our community,” says executive editor Mitch Pugh about coverage decisions. “We listened a lot. Maybe not as much as we should have at first, but as these stories continued, I think we realized we needed to listen more.” A few of their journalists, such as Jennifer Berry Hawes, Glenn Smith and Doug Pardue, “understood the limitations of their own experiences and did their very best to ensure their stories reflected what was really happening in Charleston and the impact on all our readers.”

But Pugh has not heard much about implicit bias testing and training options. “We are woefully behind in terms of building a newsroom that accurately reflects our community,” he says. “But we have to be better. Plain and simple. The nature of some of the biggest news stories of the last five years has forced us to reckon with issues we’re likely more comfortable avoiding.”

While virtual reality and other efforts have shown promise, there is no guaranteed solution to correcting for implicit bias in news coverage

The New York Times has mandated implicit bias training for all hiring managers, which must be completed before managers conduct interviews. Like many other organizations dealing with the issue, the company believes a newsroom-wide mandate might make the training less effective. But it has been made available to non-managers, and hundreds have voluntarily taken it.

National editor Marc Lacey has found the program helpful. “It prompts you to question your assumptions,” he says. “It prompts you to not assume that your first judgment of something is the right one. It prompts you to realize that there are points-of-view other than your own. All of these things are healthy for good reporters. It’s not just one group that has unconscious bias; it is something that everybody on the planet has and is something we can work on.”

Though the Times employs journalists from all over the world and has committed to training designed to eliminate blind spots, it has not been without controversy. The Times was heavily criticized for a piece that got pilloried as “the Nazi next door.” Its coverage in the lead-up to the 2016 presidential election, particularly a piece that suggested the investigation into the Trump campaign was bearing no fruit even as it featured an abundance of critical stories about Hillary Clinton’s email usage, has been scrutinized. Critics claim the paper has had a long-running bias against the 2016 Democratic presidential nominee.

Does that suggest diversity and implicit bias training isn’t all it’s cracked up to be? Not necessarily, says Lacey, who believes the training should be embraced by more in the industry. “Taking unconscious bias training does not mean that every story that one handles in the weeks and months and years after that training is going to be without criticism and that everybody is going to like that story,” Lacey says. “It won’t result in perfect journalism. What it does is prompts one to be reflective.”

NPR has also been tackling the issue. The podcast “Code Switch,” hosted by Shereen Marisol Meraji and Gene Demby, is one of the most high-profile, tangible manifestations of a national media outlet’s attempt to contend with its blind spots concerning race. NPR has not required journalists to take the implicit bias test, but its human resources department brought in an implicit bias trainer last year for a few workshops. Keith Woods, vice president for newsroom training and diversity, hopes to conduct more this year. New hires participate in orientation workshops held monthly during which they talk about coverage of race issues. Such discussions also take place when news desks and shows are grappling with coverage questions.

The New York Times has mandated implicit bias training for all hiring managers, which must be completed before managers conduct interviews

Still, Woods doesn’t believe “we do a good job at all wrestling with racial bias” because, “like the rest of society, we’ve pushed the issue of bigotry so far to the extreme in our heads that unless you’re wearing your sheets at night or sporting a swastika tattoo, you don’t regard that as a personal challenge. People believe that if they’re already on the side of the angels as a journalist, they’re not the ones who need the work. The reality is that we all need it.”

The difficulty is having a sustained commitment.

“There’s only one way to improve this: more talking,” Woods said. “There have been times in the eight years I’ve been at NPR when we were doing that better than we are now, but it’s never been enough. Like everywhere, we struggle to find the time or money, or the people motivated enough to pull those conversations together.”

He has noticed a difference in how white journalists and journalists of color view NPR’s efforts, a split not unique to NPR. That phenomenon showed up during the 2016 election cycle when many journalists of color were exasperated by the “economic angst” narrative embraced by many white journalists to explain why blue-collar white voters chose Donald Trump. “White journalists not pressing the question much; journalists of color often frustrated by what does and doesn’t get covered or how it’s covered,” he says. “But that’s a surface description. Our most recent sourcing research tells us that Latinos, for example, aren’t included much by anyone but Latinos. And every racial group has blind spots about somebody else.”

Other outlets are grappling with these issues in a variety of ways that touch on various biases, implicit and otherwise. National Geographic put together an entire issue to examine race, as well as the magazine’s own racist history. Journalists such as Wesley Lowery of The Washington Post have said other media organizations should examine their history with race. The Financial Times is examining ways to better reach women, who only make up roughly 20 percent of its subscribers.

Ed Yong of The Atlantic has been open about the difficulty of trying to “fix the gender imbalance,” in his articles through self-audits. He was surprised to learn that 35 percent of his stories in 2016 included no female sources, and he used men as sources more than three-quarters of the time in his stories. A colleague of his found that women made up less than a quarter of her sources.

It took effort, but Yong increased those numbers, adding an estimated 15 minutes of work per piece to his workload. Since then, he’s been using lists of tips that teach journalists how to diversify sources and a database of underrepresented experts in science, the field he covers. It’s the kind of effort that can lead to enriched stories that better illustrate the complex reality of the world—while serving as a bulwark against implicit bias.

To combat their blind spots, Tim Carney, commentary editor at the Washington Examiner, says his writers sit at the same desk and talk through issues. His staff includes two immigrants, one a Pakistani Muslim, and a mix of “Midwesterners, Northeasterners, rural folk, city folk, millennials, Gen X-ers.” They speak freely about difficult issues, he says. “On the most difficult issues like race and sexuality, we really try to press one another to think through the issues from everyone’s perspective. It helps that we have diversity but also are fairly unified ideologically. In other words, I think we talk more openly about race and ethnicity at our desk because we’re all conservatives and not worried about some opportunistic liberal jumping out and calling us racist.”

But conservatives have a few disadvantages when it comes to seeing clearly on race, Carney says. They’ve been called racist publicly so frequently it “inures us to complaints about microaggressions and implicit bias.” Young conservatives are likely to believe that perspective doesn’t matter, which makes it harder to sympathize with others or examine their own biases. And conservatives simply don’t have as many black and Hispanic people “among our ranks.”

Carney says he will consider implicit bias training for the opinion page at the Examiner. He knows well that “one’s experiences matter. It’s a contradiction to state that journalists can and do cover issues objectively and that race matters.”

Objectivity is a nebulous term. Still, for the longest time, white male journalists set the standard for objectivity, which was affected by their experiences and background even when they didn’t acknowledge that reality. And for a long time, I let broadcasters off the hook because I was convinced they had objectively considered having a stutterer like me on the air before objectively turning me away. That’s why it took nearly a decade before my voice was heard on NPR airwaves.

No reputable journalistic outfit can credibly claim ignorance about blind spots that affect coverage

I began to gently push back because I wanted those broadcasters to realize that the infrastructure they built to produce a daily or weekly show works well for what it’s been designed to do, which means almost always excluding potential sources who are inconvenient, no matter how much value those sources may bring to an on-air discussion. I wanted them to know that journalists must decide if the convenience of the status quo is more important than the disruption of eliminating journalistic blind spots, in hiring and coverage decisions. Those of us who present real difference can’t just be shoved into programs designed for people unlike us.

That’s why warnings from skeptics of implicit bias tests and training should not be ignored. Among the skeptics is Olivia Goldhill, who says the implicit bias narrative “lets us off the hook. We can’t feel as guilty or be held to account for racism that isn’t conscious,” she wrote for Quartz in December. “The forgiving notion of unconscious prejudice has become the go-to explanation for all manner of discrimination, but the shaky science … suggests this theory isn’t simply easy, but false. And if implicit bias is a weak scapegoat, we must confront the troubling reality that society is still, disturbingly, all too consciously racist and sexist.”

Goldhill cited a recent meta-analysis that looked at 492 studies from several researchers, which found that “changes in implicit measures are possible, but those changes do not necessarily translate into changes in explicit measures or behavior.”

That remains among Goldhill’s primary concerns about implicit bias tests, or even attempts to definitively declare what result is or isn’t caused by implicit bias. “Journalists should be focusing on behavior. I’d be very careful about referring to anything as ‘implicit bias’ without evidence,” she says. “I do not think racist police shootings or the lack of women in senior positions can be unequivocally attributed to unconscious prejudice. Within the newsroom, as in all offices, I think the focus should be on behavior, and there should be repercussions for prejudiced behavior … I think using data to monitor articles and how various groups are portrayed helps create clear evidence of bias and shows how articles need to change.”

Ultimately, for Goldhill, “If you act in a prejudiced way, then you should be held accountable,” she says. “Far too many people shirk responsibility by suggesting their unconscious is to blame, rather than themselves.”

Jennifer Dargan, a Knight Fellow who took a leave of absence from Wisconsin Public Radio to research the subject, urges journalists to participate in workshops like those created by Mosley and Desmond-Harris. They include history lessons, solid definitions of bias and exercises “around getting comfortable talking about your own social identities.” She also recommends training by Patricia Devine of the University of Wisconsin, which “approaches prejudice, the action you take on a bias, as a habit to be broken.” That training resulted in increased hiring of female faculty in science, technology, engineering and medicine departments and showed that participants were more likely to speak up about racism two years later, she says.

“In my personal experience at Wisconsin Public Radio, I have seen diversity training lead to conversations about coverage, changes in coverage, reflections of coverage,” Dargan says. “I have also seen more acceptance about the need for diverse teams as a result of learning about bias.”

She doesn’t want to make sweeping claims about the effects of implicit bias awareness or training in newsrooms. It’s just too new to know or provide many concrete examples about change that can be directly linked to that rising awareness and training. “It’s a hard thing to measure; it’s not like measuring how many clicks you get on an article,” Dargan says. Some of the ways to measure effectiveness include more diversity among colleagues, sources, and audience, and better retention of employees from marginalized communities.

It is a choice to try to tackle blind spots or leave them as is, no matter if the bias is implicit or explicit

Which brings me back to questions about implicit bias concerning me and my stutter. How will I ever know if I had been left out of stories for a decade because of implicit or explicit decision-making? Does the answer to that question matter more than the reality that I had been excluded for all those years? I’ve decided to stop wondering and start focusing on what broadcasters can do to make sure people like me aren’t left out any longer.

To accommodate someone like me, broadcasters will have to commit to treating me differently – because I am different. That may even mean leading the segment with a brief explanation about why I sound different than the typical guest.

No reputable journalistic outfit can credibly claim ignorance about blind spots that affect coverage. It is a choice to try to tackle those blind spots or leave them as is, no matter if the bias is implicit or explicit. And while I understand the hesitance to make bias training mandatory, I can’t help but think that’s evidence the industry isn’t quite ready to change. The value of the implicit bias debate is that it’s becoming clearer that journalists can—and must—decide.