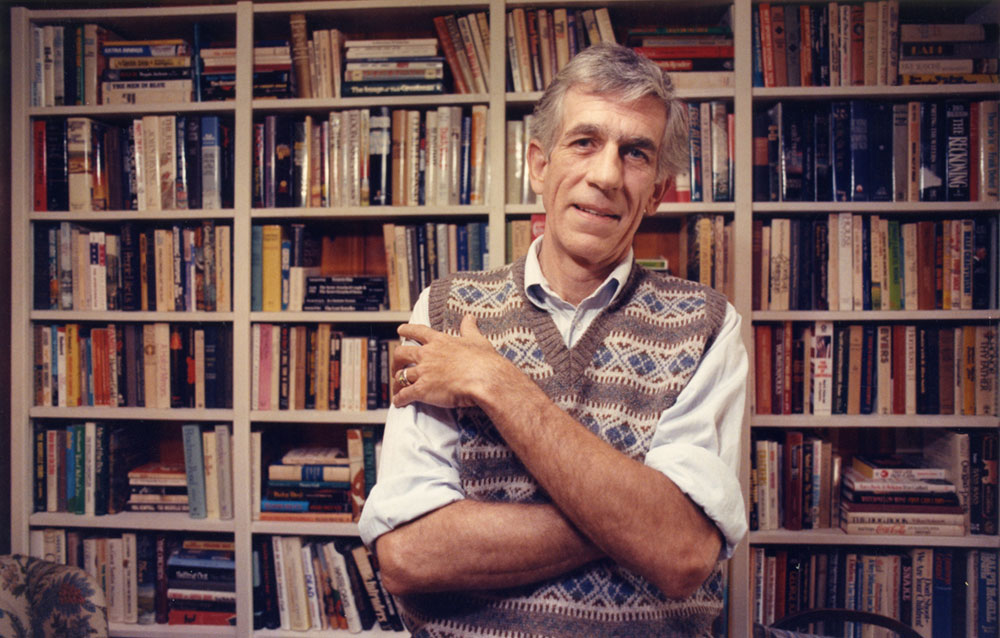

One of the eternal struggles for journalists is between the need to belong to something bigger than themselves and the urge for independence. Nearly every reporter hopes to be part of a like-minded organization—whether newspaper or online news site—that offers professional support and camaraderie, not to mention a regular paycheck and health insurance. At the same time, most chafe at the restrictions and monotony of working for the information factory. How many city council meetings or high school basketball games can you cover before you start to die? This is the conundrum Paul Hemphill (Nieman class of 1969) addresses in his bitterly trenchant essay, “Quitting the Paper.” Hemphill, the featured daily columnist at The Atlanta Journal during the late 1960s, was once the most widely read journalist in the South. He pounded out six columns a week, and at their best they were literature on deadline. Ultimately, however, he wanted to take a stab at writing books. In “Quitting the Paper”—which appeared in 1974 in Southern Voices (an excellent but short-lived glossy) and which I devoured as a journalism student at the University of Georgia—Hemphill makes the case for going it alone. His brief, while somewhat melodramatic (Hemphill was always the star of his own movie) and slightly dated (in the 1970s, the news biz was so healthy you could leave a good job confident that if your ambitions faltered you’d find another just as good), captures the never-ending tension between journalistic stability and freedom. The chilling kicker about Birmingham News sports editor Benny Marshall says it all. From the moment I finished the piece, I knew I would never be a lifer anywhere.

Quitting the Paper

By Paul Hemphill

Southern Voices, 1974

Excerpt

Late one night in the fall of 1969, with the rain splattering against the front window and the gray light of a television set dancing across the bar, I sat in a booth at Emile’s French Cafe in downtown Atlanta with a feisty young newspaper reporter named Morris Shelton and methodically proceeded to get paralyzed on Beefeater martinis. By now this had become a daily ritual. I was thirty-three years old. I was the featured columnist for the Atlanta Journal, the largest daily newspaper between Miami and Washington. I had been one of a dozen journalists around the country to be selected to study at Harvard under a Nieman Fellowship the previous year. I fancied myself a Jimmy Breslin of the South, cranking out daily one-thousand-word human dramas on everything from flophouse drunks to Lester Maddox, sufficiently loved and hated by enough people to have that sense of pop celebrity with which most newspapermen delude themselves. I had the most envied newspaper job in Atlanta, if not in the South, and now and then I would see a younger writer in a town like Greensboro or Savannah or Montgomery imitating my style just as I had once stolen from Hemingway and Breslin and too many others to talk about. I had been sloppy and inaccurate, from time to time, but I had also written some good stuff. I had hung around all-night eateries and gone to Vietnam, and hitchhiked and lain around with hookers and shot pool with Minnesota Fats and sat in cool suburban dens with frustrated housewives.

And yet, with the next column due by dawn, I had run out of gas.

Reprinted with permission from the estate of Paul Hemphill. The piece was originally published in SOUTHERN VOICES, then reprinted in TOO OLD TO CRY, a collection of his journalism published by Viking in 1981.