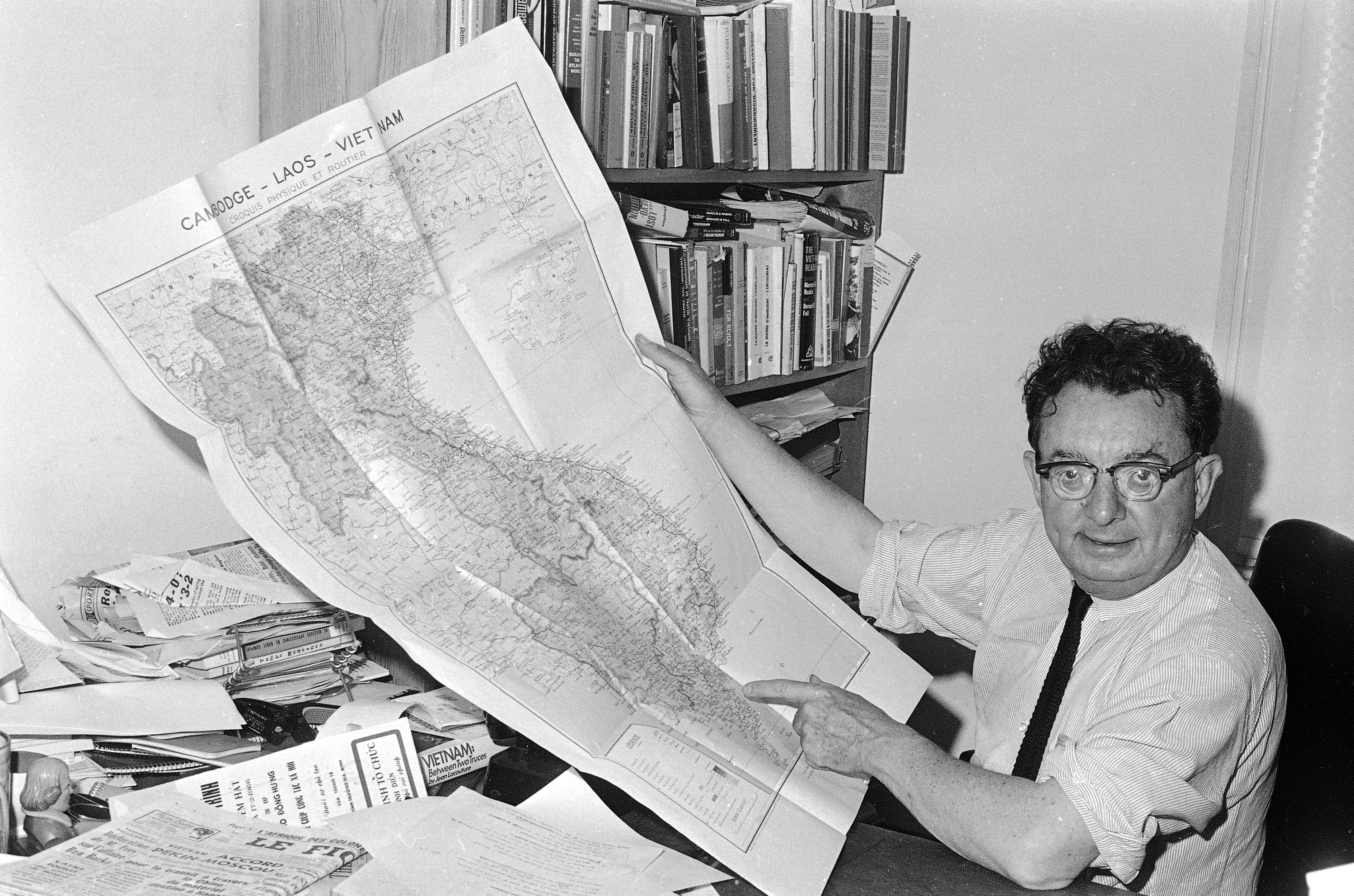

Izzy Stone taught a generation of reporters the bedrock principle that a reporter should never start with the presumption that people in powerful positions tell the truth. Digging deeper and more broadly into public documents others did not see or ignored, he consistently reported facts missed by national newspapers in his I.F. Stone’s Weekly, published from 1953 to 1971. His reporting on McCarthyism, civil rights, and the military-industrial complex provided a model for a generation of independent investigative journalists. Returning home disillusioned after four years of service in the Navy during the Korean War, I had planned to study marine biology. But that plan was hijacked when a friend working on the local newspaper introduced me to Izzy Stone’s work.

Lyndon Johnson Lets the Office Boy Declare War

By I.F. Stone

I.F. Stone’s Weekly, June 9, 1965

Excerpted in “The Best of I.F. Stone”

Public Affairs, 2006

There seems to be a peculiar division of labor here in Washington. The President makes peace speeches and the Pentagon makes foreign policy but the unpleasant task of declaring war is left to the poor State Department. The news that U.S. troops in Vietnam have been authorized to engage in full combat is the news that we are embarking on a new war. Article I, Section 8, of the Constitution, that half-forgotten document, put the power to declare war in the hands of Congress. Its members might insist at least that they have the right to hear declarations of war from some official higher up than the press officer of the State Department. It is hard to find any Constitutional or administrative reason to explain why Robert J. McCloskey, the press officer, should have been pushed suddenly into the pages of history by being assigned the task of announcing at his daily usually routine and almost always boring, noon press briefing that we were no longer advising or patrolling or defensively shooting back in Vietnam but going full-scale into war. As a major decision, it should have been announced at the White House. As a change in military orders, it might have been made public at the Pentagon. As a hot potato, both seem to have passed it on to the State Dept. There in turn it was passed on down from the Secretary through the many Assistant Secretaries to the lowest echelon available. Maybe the higherups are hoping it will be called not Johnson’s or McNamara’s but Bob McCloskey’s war.