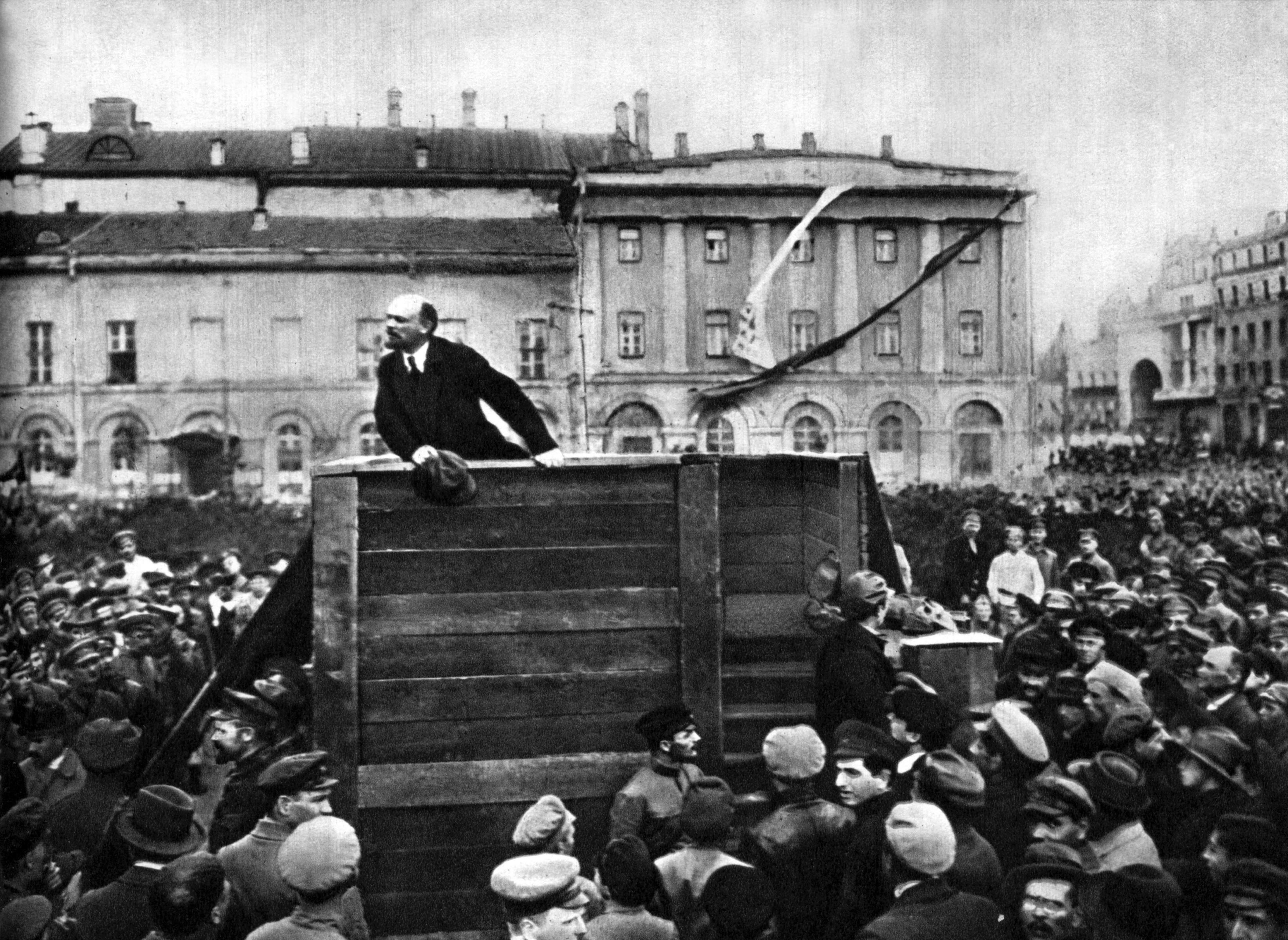

“1920 Diary” by Isaac Babel has resonated with me for many years. Babel was a Russian-born journalist and writer of Jewish descent. At age 26 he was embedded with the Bolshevik Army going West, aiming to conquer Europe. The Red Army’s march to the West was stopped in the summer of 1920 by the Polish military. Isaac Babel’s official job was to write for a state press agency. His more important job was to write—with deep humanity—a secret diary documenting the brutality, cruelty, and senselessness of the war. If the diary had been found at the time, the author would have been immediately shot as a traitor (indeed, he was shot years later by the communists, but for a different reason).

What I have learned from repeatedly reading Babel’s diary is the power of the disciplined and minimalist language he used to depict the inhumanity of the war, speaking truth to the brutal and primitive power of the soldiers, the army, and the war itself.

1920 Diary

By Isaac Babel (edited by Carol J. Avins, translated by H. T. Willetts)

Yale University Press, 1997

Excerpt

AUGUST 28, 1920. KOMAROW

Evening—at my landlord’s, a conventional home, Sabbath evening, they didn’t want to cook until the Sabbath was over.

I look for the nurses, Suslov laughs. A Jewish woman doctor.

We are in a strange, old-fashioned house, they used to have everything here—butter, milk. At night, a walk through the shtetl. The moon, their lives at night behind closed doors. Wailing inside. They will clean everything up. The fear and horror of the townsfolk. The main thing: our men are going around indifferently, looting where they can, ripping the clothes off the butchered people.

The hatred for them is the same, they too are Cossacks, they too are savage, it’s pure nonsense that our army is any different. The life of the shtetls. There is no escape. Everyone is out to destroy them, the Poles did not give them refuge. All the women and girls can scarcely walk. In the evening a talkative Jew with a little beard, he had a store, his daughter threw herself out of a second-floor window, she broke both arms, there are many like that.

What a powerful and magnificent life of a nation existed here. The fate of the Jewry. At our place in the evening, supper, tea, I sit drinking in the words of the Jew with the little beard who asks me plaintively if it will be possible to trade again. An oppressive, restless night.