In the early morning of December 15, 2005, three teenage girls were killed in a traffic accident while on their way to school. This happened in Chongqing, one of the biggest cities in China. The three families received different rates of compensation: According to the girls' families, 200,000 RMB was given to the family of each girl who had an urban household registration; 50,000 RMB was given to the family of the girl with a rural household registration. [There are eight renminbi, RMB, to one American dollar.]

This unequal treatment reveals the urban/rural and income gaps that are deeply rooted in China and strengthened by law and policy. And different news media in this country handle the reporting of stories like this one in different ways.

As the Lunar New Year approached in late January, on the front page of the People's Daily, the official newspaper of the central committee of the Chinese Communist Party, a special column appeared with the title, "Sending Warm Regards, Giving a Good New Year." What follows are news items that appeared in this column on January 22, 2006:

- Central government appropriates 17 billion RMB as pension security subsidy for enterprise employees.

- Party members among central government and party organs send warm hearts with money and goods, all of the donation arrived into the hands of people who have the needs.

- Free health check-up for 63 cleaners in Jinan, Shandong Province.

- In Xian, Shaanxi Province: 800 model workers have gotten one million holiday subsidy from city government.

- In Dalian, Liaoning Province: Union mobilizes 16.4 million RMB, helps difficult migrant workers go home for holiday family reunion.

- In Zhangjiakou, Hebei Province: Ensure 170,000 difficult people have a safe winter, 64,000 party members help 18,000.

Along with this column, there were news stories related to ways that the government is working to bridge social and economic gaps:

- Fujian Province: all new provincial financial income is spent for agriculture, rural areas, and farmers.

- Hainan Province: financial spending focuses on things that benefit people.

- And a story entitled, "We did not expect to receive New Year call as a farmer."

More than a half of the news stories on the front page on this day were related to disadvantaged people. That kind of coverage is unusual and is likely happening now because of the Chinese New Year, the country's most important festival. But still it sheds light on the more typical way that the official media cover these gaps in China.

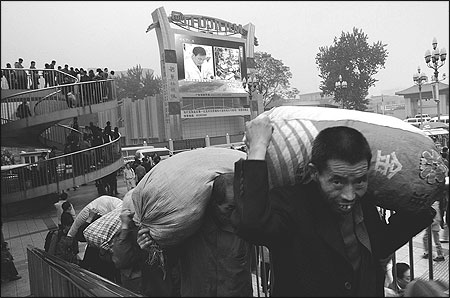

In the past few years, as the government started talking about building a harmonious society and began working on its Scientific Review on Development, the three new big societal gaps identified were urban/rural, east/west, and rich/poor. That there are three new large gaps is a reminder of the historic "Three Big Gaps" theory during the Mao era. Then the gaps were urban/rural, worker/farmer, and mental labor/manual labor, and the slogan was "Eliminating the three big gaps, toward the ideal Communist Society."

Mao's policies did indeed reduce income and social status gaps between mental and manual labor by degrading the former, but did not close the other two. In the early to mid-1980's, reformers among the party's leaders did reduce some of the urban/rural and worker/farmer gaps, however, by enhancing the latter. However, gaps among industries, regions and the haves and have-nots were still built-in, and in recent years these have even expanded in some regards.

Gradually, the topic of social gaps has received attention from scholars and those in the media, and more articles and stories about them have appeared. There are different approaches to covering these issues, since the media in China can be divided into two general categories — the official news media and the commercial one, which is also under the control of the party and state government. The typical official style is seen in what was shared above from the People's Daily: Most of what appears is good news about what the authorities have done to resolve the problem.

From the official news media, readers cannot get a very good understanding about the presence or significance of these gaps, nor is there any mention made of the structural factors that are causing them or helping them to persist. Nor can readers learn about efforts being made by nongovernmental organizations and other institutes in unconventional ways. When it comes to talking about causes for these gaps, official mouthpieces might mention them in very abstract ways, if they talk about them at all. Terms used to refer to gaps often appear in jargon, and usually numbers are used and few human stories are told. If people's experiences get written about, stories fall into a predictable formula: victims become beneficiaries and the state and party leaders act as patrons, and the former are grateful to the latter. Readers can hardly find in-depth and down-to-earth stories.

Commercial media differ. On the one hand, these media have some in-depth stories, and they are more attractively told for readers. One reads some human stories and in doing so feels how people are affected by poverty and social inequality. Some stories go further to reveal deep roots of the problem, and they explore the resolution of the problem from a systematic or structural angle. At the same time, however, many of these reports have visible faults: The writing is done sensationally, so that vulnerable people like women are portrayed simply as victims/losers, sometimes as isolated cases, and their problems are personalized. In these stories, there is a failure to probe structural factors that caused their problems. Some of these reports just blame the victim and offer no hint, background, or comprehensive analysis. Stories showing how people try to change the unfair institutional arrangement and improve their situation are rarely seen, and very few media outlets, among hundreds and thousands of them, have published stories that reveal the emergence of activists and citizen movements to secure people's rights.

The Gender Gap

Coincidently, both the official and commercial news media have paid much less attention to gender gaps. For example, women retire at an age five years younger than men do, and this was allowed by law even though it is against the equal rights principle of the constitution. Women's organizations called on this to be changed for many years, but this issue did not become a major media topic until recently. The events about Beijing +10 — which was the 10-year review on the follow-up action of the commitments made by governments at the World Conference on Women held in Beijing by the United Nations in 1995 — more involved a celebration than a chance to reflect on gender gaps that remain, and are even expanding in some areas.

If one searches through recent years of the People's Daily, one finds about 500 items that mention the gaps between rural and urban Chinese and more than 1,200 items in which "income gap" or rich/poor gap is cited. But only 12 stories mention gender gap, even though the income gap between men and women increased by seven percent in urban China and 19 percent in rural China during the 1990's. During this same time, the employment rate of women dropped more than it did among men.

Along with reporting on these gender gaps, issues of discrimination also fall under the light of media attention. Regional discrimination under hukou, the system of household registration by area, which determines whether family members receive certain benefits and opportunities, and discrimination in health care, along with other forms of discrimination, are becoming topics of press coverage.

Ironically, gender discrimination is not very visible in the media. Among 2,103 stories that mentioned discrimination, only about 100 mentioned "gender discrimination." In the fall of 2005, Beijing University required women applicants for a given department to score higher during their recruitment; when this became known, much of the news media gave more space and bigger voices to the opinion that this is not a clear-cut example of gender discrimination. When women's voices are not heard, gender inequity is not a visible issue in the media. If journalists don't value this topic, how can we expect more comprehensive coverage on social gaps and a harmonious society?

Now harmonious society has become a fashionable term among China's leaders and media. But how is this harmonious society to be interpreted? Some stress exists about whether it is better to maintain stability and ignore the inequity to keep the status quo. It is also very difficult for China's structural factors to be touched. There are some people who interpret the words "harmonious society" to mean that there should be a society in which everyone has food and has a voice; this interpretation is signaled by the two Chinese characters that make up the word harmony.

How can the news media in China do better? They face many challenges; the dilemma for them is how to push the limits while following the party's guidelines. On January 24, 2006, Chinese authorities closed Freezing Point, which had been a section of China Youth Daily since the mid-1990's and was almost the only outspoken media space among official newspapers. A month earlier, the party authority removed the editor in chief of The Beijing News, a lively newspaper that had been jointly published since November 2003 by an official newspaper belonging to the Central Committee of the Communist Party and the Southern Metropolitan News, a "child newspaper" of Guangdong Provincial Party's newspaper group. The publication of The Beijing News was allowed by special permission of authorities, and as time went on its performance was beyond what the party would accept. It is difficult to know how to make journalists keep their probing eyes while under restraint.

Yuan Feng, a 2002 Nieman Fellow, is a co-coordinator of Media Monitor for Women network in Beijing.