A leader in digital innovation and editorial strategy, S. Mitra Kalita has had reporting jobs and leadership roles at news organizations spanning multiple platforms and locales, from New York to D.C. to India to L.A. She’s worked for The Washington Post, Newsday, and the Associated Press, and was the founding editor of Mint, a business paper in New Delhi. After directing global economics coverage at The Wall Street Journal, she was the executive editor at large—as well as the first ideas editor—at Quartz, where she helped oversee the launches of Quartz India and Quartz Africa. Most recently, Kalita was the managing editor for editorial strategy at the Los Angeles Times, helping latimes.com traffic nearly double in the year she was there, reaching nearly 60 million unique monthly visitors in 2016.

Currently Kalita is the vice president for programming for CNN Digital, a role which she assumed last June. Leading CNN Digital’s efforts to share content across platforms, she also oversees the network’s News & Alerting, Projects & New Initiatives, Mobile & Off-Platform, and Real-Time News teams.

Kalita spoke at the Nieman Foundation in March. Edited excerpts:

There’s a diversity theme that runs through my career. It's not a strategy. It's not just a thing I talk about at conferences, but it really is how I live my life and how I commit journalism.

I think part of the reason is because of how I got into journalism. When I was 16 years old, I attended a minorities journalism workshop. On the first night, they gathered the group of us, kids from across New Jersey who all had worked on their high school newspapers. We watched a movie called “Boyz n the Hood” as an activity in the dorm. There was a scene that changed everything, [where the character played by Ice Cube says of society and, more pointedly, the media,] “They don't know. They don't show. They don't care about what's going on in the hood.” Basically, he's just saying no one cares about us. No one cares about people in the hood.

“They don't know, they don't show” —those words just penetrated me. It was partly the environment. You're probably the most idealistic you're going to be when you're 16.

So I thought: If I were to just show stories and show people themselves, what would that look like? "They don't show," has been the refrain of my career.

I used to think of CNN as like a utility. Something happens and you turn to CNN. That's such amazing power and reach. What does that look like in a mobile age? Is it actually that [mobile] isn't the second screen for a CNN, but is the first? These are the philosophical questions that we talk about.

As we're trying to cover this administration, it plays into design decisions that we're making. For example, our homepage used to be largely driven by one big story. But what do you do on a day when Trump is giving a press conference, Steve Bannon might be at the National Security Council, there's a congressional hearing for a cabinet confirmation, and we're trying to offer context of what this all means? You'll see that the CNN homepage now might look busy, but I would like to think that our design and philosophy show an ability to be in many places at once. We don't have the one‑story imperative of television.

Moving to the LA Times from Quartz was the chance to truly take the lessons of a start-up environment, specifically a digitally native outlet, [and apply them to the local journalism].

I felt like I might be able to try to have the coverage of newspaper reflect the phenomenon of our times, which might not mean covering beats, buildings, or institutions in the traditional way. LA, which is so vibrant and so creative, it's a majority-minority city. So, it felt like a tremendous opportunity to draw on all of my lessons about communities of coverage and having those communities inform your storytelling along the way as we did with Dexter [Thomas’s] work [covering black Twitter], where he is out among the community even as he's reporting on them. I would say we were very successful. I can't think of another newspaper in America where I would have been able to hire somebody to cover black Twitter. I felt our efforts were working.

The challenge is that, in a publicly traded newspaper chain, you don't have a terribly long runway or the ability to make the investment of what it takes to sustain daily relevance in a city like Los Angeles. It is a tremendous challenge to see a newsroom go from—I think at one point, I think it had over 1,000 people—to less than half that today, and still be able to do ambitious journalism.

There's also the reality of, for someone like me, who's a change agent feeling caught between the model that you've inherited and a newsroom that you're trying to change even as you're trying to defend it against forces. I think a part of the reason I was able to make fast changes is because the newsroom understood it needed to change and I had a lot of conviction about what we needed to do to become more relevant to new audiences.

In a majority‑minority city, if you're not reaching a Latino population, you're doing something wrong. When there is a massive gas leak, you’ve got to reach out to that community. During the Aliso Canyon gas leak, we used a Google Form to gauge health effects: "Do you have bloody noses? Do you have problems breathing?" To me, that feels like just good community journalism, but those were things that we were able to do, because we hired a community editor. We did things that, I think, made the LA Times again feel palpable, as, "We are your paper." If you know yourselves and what you stand for in a newsroom, you know your readers and your readers start to identify themselves in the stories that they're seeing. They see themselves. So you start to see a refrain of how I like to approach things.

I was able to make quick changes, because I think I was naïve about what I was up against, and maybe that's a good thing. I read the LA Times now pretty much still every day, and I marvel at what I'm seeing. They did a great series about Trump, arts and the election, "Has Hollywood lost touch with American values?"

Lasting change is really hard, which is perhaps why I have gravitated to start-ups, because you're able to establish the mission. You want newsrooms to always expect change, with a constant of embracing audiences and stories. Your allegiances are to audiences and to stories versus fiefdoms and who reports to who, and this and that, which, of course, all newsrooms get obsessed with.

You definitely want to create more flexible ways of thinking, and I think that's been the narrative of this stage of my career.

Someone like a Van Jones on CNN has seen great success on air as well as online. A lot of people see him as speaking the words that they're thinking.

Van Jones is also a big social media hit for us because people share his video, his opinion pieces, or his series on “The Messy Truth” where he’s sitting down and talking to Trump voters and understanding motivations and so forth. He suddenly represents readers in a way that the traditional journalist might not.

I know that there are people who say, "Oh, that's not really journalism." It was really at Quartz where I became open to redefining the role of the journalist. … It might be a different lens on the story than you're used to. That's OK as long as there's real clarity and transparency for the audience. I give a lot of credit to audiences.

We have some intentionally experimental journalists on the social media team. My colleague, Masuma Ahuja, for example, she’s on Kik, which is the teenage messaging service and she does a lot with quizzes and delivering news in shorter bursts on that platform.

She is intentionally experimental on those platforms. Now, and importantly, she does use what she's learned from messaging and brings it back to the main platform, which is cnn.com. We will do things like voicemail projects—we did this after the election, where we asked people to call us up and tell us how they were feeling, and we got like 10,000 voicemails.

To me, her experimenting has everything to do with her success on our main platform, just because she's talking to people all day long in a different form. It informs the way that she's doing journalism. She's opening up our platform and is informed by messaging apps and some of the other platforms that she's on.

For something like Google Home [the voice-activated speaker powered by Google Assistant], we're making nominal money off of it but we feel we need to be there. I don't yet know how it's going to be consumed. That's where we went to a third‑party vendor, and they're taking CNN content, and we are there. Then in the second quarter of this year, I'll have something to work with and then figure out do we devote resources to it and what do I know about this audience.

That's how the decision‑making goes. It's very much platform‑by‑platform, which is really resource intensive. We do need to figure out how are we going to customize our content to meet people in the places that they are, in the way that they want to get news.

Currently Kalita is the vice president for programming for CNN Digital, a role which she assumed last June. Leading CNN Digital’s efforts to share content across platforms, she also oversees the network’s News & Alerting, Projects & New Initiatives, Mobile & Off-Platform, and Real-Time News teams.

Kalita spoke at the Nieman Foundation in March. Edited excerpts:

On the refrain of her career

There’s a diversity theme that runs through my career. It's not a strategy. It's not just a thing I talk about at conferences, but it really is how I live my life and how I commit journalism.

I think part of the reason is because of how I got into journalism. When I was 16 years old, I attended a minorities journalism workshop. On the first night, they gathered the group of us, kids from across New Jersey who all had worked on their high school newspapers. We watched a movie called “Boyz n the Hood” as an activity in the dorm. There was a scene that changed everything, [where the character played by Ice Cube says of society and, more pointedly, the media,] “They don't know. They don't show. They don't care about what's going on in the hood.” Basically, he's just saying no one cares about us. No one cares about people in the hood.

“They don't know, they don't show” —those words just penetrated me. It was partly the environment. You're probably the most idealistic you're going to be when you're 16.

So I thought: If I were to just show stories and show people themselves, what would that look like? "They don't show," has been the refrain of my career.

On CNN in the digital age

I used to think of CNN as like a utility. Something happens and you turn to CNN. That's such amazing power and reach. What does that look like in a mobile age? Is it actually that [mobile] isn't the second screen for a CNN, but is the first? These are the philosophical questions that we talk about.

As we're trying to cover this administration, it plays into design decisions that we're making. For example, our homepage used to be largely driven by one big story. But what do you do on a day when Trump is giving a press conference, Steve Bannon might be at the National Security Council, there's a congressional hearing for a cabinet confirmation, and we're trying to offer context of what this all means? You'll see that the CNN homepage now might look busy, but I would like to think that our design and philosophy show an ability to be in many places at once. We don't have the one‑story imperative of television.

On change at the LA Times

Moving to the LA Times from Quartz was the chance to truly take the lessons of a start-up environment, specifically a digitally native outlet, [and apply them to the local journalism].

I felt like I might be able to try to have the coverage of newspaper reflect the phenomenon of our times, which might not mean covering beats, buildings, or institutions in the traditional way. LA, which is so vibrant and so creative, it's a majority-minority city. So, it felt like a tremendous opportunity to draw on all of my lessons about communities of coverage and having those communities inform your storytelling along the way as we did with Dexter [Thomas’s] work [covering black Twitter], where he is out among the community even as he's reporting on them. I would say we were very successful. I can't think of another newspaper in America where I would have been able to hire somebody to cover black Twitter. I felt our efforts were working.

The challenge is that, in a publicly traded newspaper chain, you don't have a terribly long runway or the ability to make the investment of what it takes to sustain daily relevance in a city like Los Angeles. It is a tremendous challenge to see a newsroom go from—I think at one point, I think it had over 1,000 people—to less than half that today, and still be able to do ambitious journalism.

There's also the reality of, for someone like me, who's a change agent feeling caught between the model that you've inherited and a newsroom that you're trying to change even as you're trying to defend it against forces. I think a part of the reason I was able to make fast changes is because the newsroom understood it needed to change and I had a lot of conviction about what we needed to do to become more relevant to new audiences.

In a majority‑minority city, if you're not reaching a Latino population, you're doing something wrong. When there is a massive gas leak, you’ve got to reach out to that community. During the Aliso Canyon gas leak, we used a Google Form to gauge health effects: "Do you have bloody noses? Do you have problems breathing?" To me, that feels like just good community journalism, but those were things that we were able to do, because we hired a community editor. We did things that, I think, made the LA Times again feel palpable, as, "We are your paper." If you know yourselves and what you stand for in a newsroom, you know your readers and your readers start to identify themselves in the stories that they're seeing. They see themselves. So you start to see a refrain of how I like to approach things.

I was able to make quick changes, because I think I was naïve about what I was up against, and maybe that's a good thing. I read the LA Times now pretty much still every day, and I marvel at what I'm seeing. They did a great series about Trump, arts and the election, "Has Hollywood lost touch with American values?"

Lasting change is really hard, which is perhaps why I have gravitated to start-ups, because you're able to establish the mission. You want newsrooms to always expect change, with a constant of embracing audiences and stories. Your allegiances are to audiences and to stories versus fiefdoms and who reports to who, and this and that, which, of course, all newsrooms get obsessed with.

You definitely want to create more flexible ways of thinking, and I think that's been the narrative of this stage of my career.

On redefining “journalist”

Someone like a Van Jones on CNN has seen great success on air as well as online. A lot of people see him as speaking the words that they're thinking.

Van Jones is also a big social media hit for us because people share his video, his opinion pieces, or his series on “The Messy Truth” where he’s sitting down and talking to Trump voters and understanding motivations and so forth. He suddenly represents readers in a way that the traditional journalist might not.

I know that there are people who say, "Oh, that's not really journalism." It was really at Quartz where I became open to redefining the role of the journalist. … It might be a different lens on the story than you're used to. That's OK as long as there's real clarity and transparency for the audience. I give a lot of credit to audiences.

On experimenting with different platforms

We have some intentionally experimental journalists on the social media team. My colleague, Masuma Ahuja, for example, she’s on Kik, which is the teenage messaging service and she does a lot with quizzes and delivering news in shorter bursts on that platform.

She is intentionally experimental on those platforms. Now, and importantly, she does use what she's learned from messaging and brings it back to the main platform, which is cnn.com. We will do things like voicemail projects—we did this after the election, where we asked people to call us up and tell us how they were feeling, and we got like 10,000 voicemails.

To me, her experimenting has everything to do with her success on our main platform, just because she's talking to people all day long in a different form. It informs the way that she's doing journalism. She's opening up our platform and is informed by messaging apps and some of the other platforms that she's on.

For something like Google Home [the voice-activated speaker powered by Google Assistant], we're making nominal money off of it but we feel we need to be there. I don't yet know how it's going to be consumed. That's where we went to a third‑party vendor, and they're taking CNN content, and we are there. Then in the second quarter of this year, I'll have something to work with and then figure out do we devote resources to it and what do I know about this audience.

That's how the decision‑making goes. It's very much platform‑by‑platform, which is really resource intensive. We do need to figure out how are we going to customize our content to meet people in the places that they are, in the way that they want to get news.

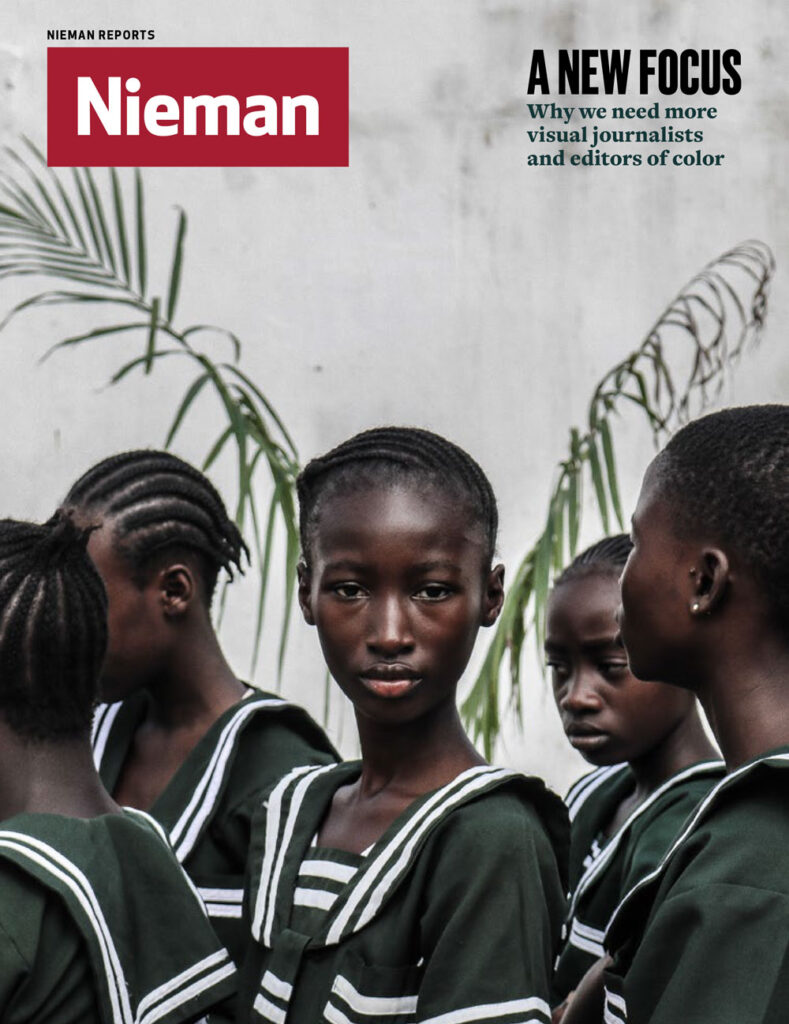

![Image for S. Mitra Kalita: “‘They don’t know, they don’t show’—those words [from ‘Boyz n the Hood’] just penetrated me. … Those words have been the refrain of my career”](https://niemanreports.org/app/uploads/2024/03/170202123132-mitra-kalita-e1551127430722.jpg)