after 15 years of assignments in war zones around the globe, I’ve found that the hopes, dreams, and nightmares of enemies are often more similar than they are different. This is the story I need to share.

In my 2013 photo project “Portraits of the Enemies,” I placed viewers in-between life-size portraits of enemy combatants. My new virtual reality project, “The Enemy,” is designed to help audiences discover a shared humanity between opposing combatants in eight conflict zones: Israel and Palestine, Afghanistan, Kashmir, Congo, South Sudan, North and South Korea, Myanmar, and El Salvador.

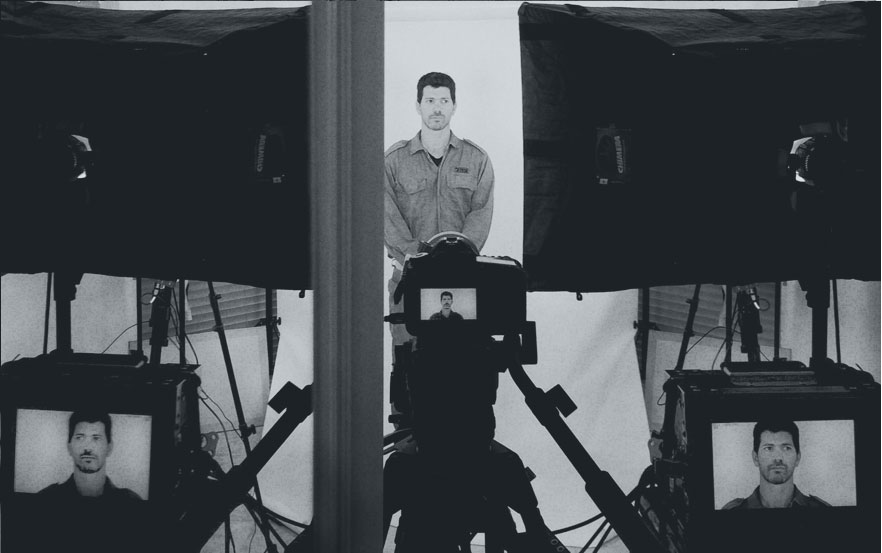

Based on interviews I’ve conducted with soldiers, we have produced a prototype that places participants in the middle of two enemy combatants who share what drives them to take up arms. As viewers don virtual reality headsets, text on the facing wall provides background on one of the conflict zones.

Two photographs, one on the wall to the participant’s left and the other on their right, show the opposing combatants. As viewers approach each of the photos, they hear sounds recorded in the conflict zone—gunshots, sirens, people panicking—and are introduced, with my voice, to the two subjects with a few details about their lives.

The photographs disappear and participants hear people entering the room. When they turn around, they find three-dimensional lifelike manifestations of the two subjects in the photographs. When approached, each soldier, prompted by my questions, explains why he is fighting. Though not interacting with each other, the soldiers appear to make eye contact, with viewers caught in their emotional crossfire.

My goal is not only to inform people, but to change the way they perceive others. Though we may not agree with the combatants, we need to see them as human beings.

The prototype was shown at the Tribeca Film Festival in April, and people’s reactions show how powerful virtual reality technology can be. I didn’t expect to see so many viewers, with no personal investment in the conflicts, break down crying.

We don’t anticipate the project to be done until early 2017, but what we have so far is already changing the way people discern “the other.” We all want the same things, and we’re all fighting for survival. That’s what I, as a storyteller and a journalist, want to address.

In my 2013 photo project “Portraits of the Enemies,” I placed viewers in-between life-size portraits of enemy combatants. My new virtual reality project, “The Enemy,” is designed to help audiences discover a shared humanity between opposing combatants in eight conflict zones: Israel and Palestine, Afghanistan, Kashmir, Congo, South Sudan, North and South Korea, Myanmar, and El Salvador.

Based on interviews I’ve conducted with soldiers, we have produced a prototype that places participants in the middle of two enemy combatants who share what drives them to take up arms. As viewers don virtual reality headsets, text on the facing wall provides background on one of the conflict zones.

Two photographs, one on the wall to the participant’s left and the other on their right, show the opposing combatants. As viewers approach each of the photos, they hear sounds recorded in the conflict zone—gunshots, sirens, people panicking—and are introduced, with my voice, to the two subjects with a few details about their lives.

The photographs disappear and participants hear people entering the room. When they turn around, they find three-dimensional lifelike manifestations of the two subjects in the photographs. When approached, each soldier, prompted by my questions, explains why he is fighting. Though not interacting with each other, the soldiers appear to make eye contact, with viewers caught in their emotional crossfire.

My goal is not only to inform people, but to change the way they perceive others. Though we may not agree with the combatants, we need to see them as human beings.

The prototype was shown at the Tribeca Film Festival in April, and people’s reactions show how powerful virtual reality technology can be. I didn’t expect to see so many viewers, with no personal investment in the conflicts, break down crying.

We don’t anticipate the project to be done until early 2017, but what we have so far is already changing the way people discern “the other.” We all want the same things, and we’re all fighting for survival. That’s what I, as a storyteller and a journalist, want to address.