I won’t be sad when another white family moves into the White House.

If Hillary Clinton becomes the next president, after a few years, there might be plenty of women looking forward to the day a man retakes the reins of the world’s most powerful nation.

I didn’t know I’d feel this way more than six years ago when I drove to a former plantation in Georgetown, South Carolina—the town where first lady Michelle Obama’s family tree has roots—on the night Barack Obama had done what had been considered improbable, if not impossible. I wanted to share the historic news with the ghosts of slaves who had toiled and endured long enough to make that night possible.

This isn’t about Obama’s performance as president. He took over a country involved in two ground wars and beleaguered by the worst downturn since the Great Depression. A country that couldn’t find, let alone kill or imprison, Osama bin Laden, and that had about 50 million people without health insurance. A country where inequality had been on the rise for decades. On most of those measures, not all, he’s helped steer us to a better place. History will likely look fondly upon him.

The image of Obama as an involved, doting father and faithful spouse during an age in which black men are often stereotyped as deadbeat, undisciplined sexual beings; his overcoming the struggles associated with the instability of a single-parent home, and forgoing a lucrative career in corporate law to serve poor people on the streets of Chicago only enhance what he represents. By objective standards, the country did well when it made him the first president since Eisenhower to twice receive at least 51 percent of the popular vote.

Despite that, I’m longing for a change because I’m just … tired.

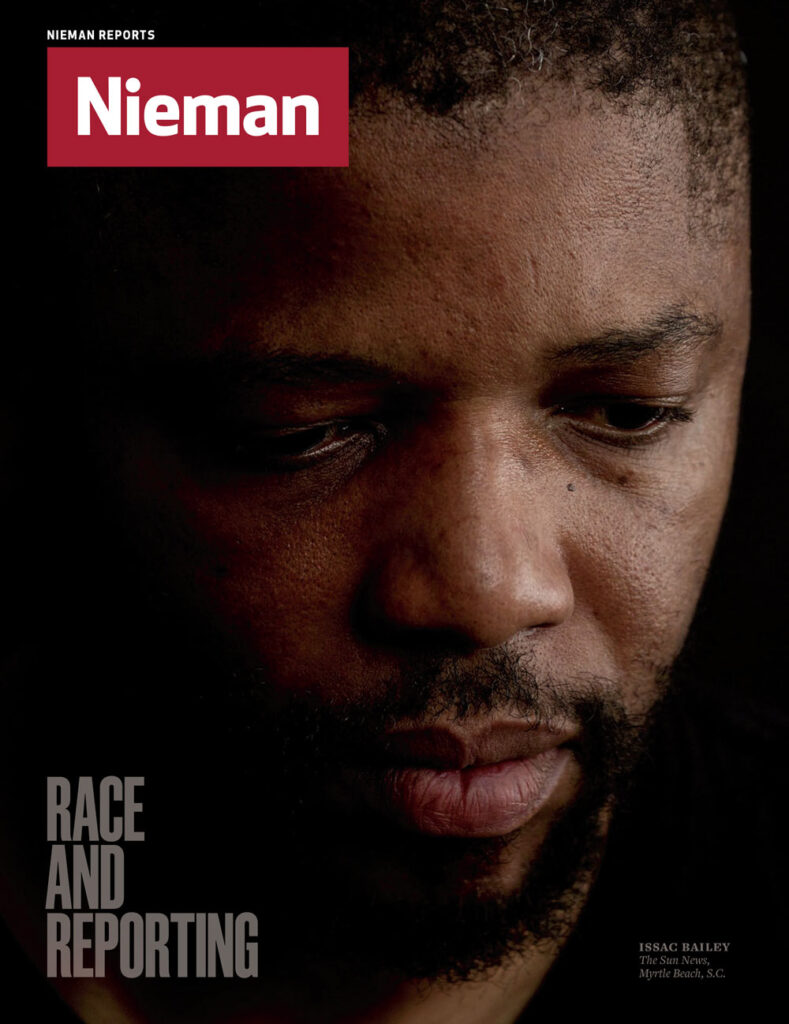

I’m tired of having to explain again and again—and again—that I’m capable of complex, rational thought concerning policy and politics in the age of Obama. I’m tired in a way I wasn’t before November 2008.

After Obama was elected president in 2008, the messages I received from readers almost overnight became overtly racist and demeaning

The shift in environment from pre- to post-Obama wasn’t subtle. The messages I began receiving from readers went almost overnight from respectfully, if bitingly, confrontational, the kind any journalist, particularly a columnist, should expect, to overtly racist and demeaning. The shift was taking place as many members of the media were talking about a nebulous post-racial world no one could clearly define because Barack Obama was about to become the nation’s first black president. The post-racial talk didn’t make room for another reality or the reason why Obama called a press conference to prove he was fully American.

I had received messages from the dark side of race relations before 2008, including threats for which the police had to get involved, as the first black dude to hold my position in Myrtle Beach, South Carolina, at the only daily newspaper in an area that is primarily white and conservative. But those came from a clear fringe: some handwritten letters marked KKK, most unnamed, many with crude threats about knowing where I live and shotguns with my name on them.

In the days before Obama’s anticipated 2008 win, white friends and fellow church members accidentally copied me on a number of forwarded chain e-mails they would have immediately deleted in prior years because they were so tasteless and racially tinged. Obama’s emergence seemingly gave them freedom to dip into a well of racial ugliness they’d refused to partake of before him. One of the messages depicted an imaginary Obama victory party, complete with a passed out homeless black man lying next to a dumpster, an overturned bucket of fried chicken, and scattered pieces of watermelon.

Those who once supported Obama but have been disappointed began to question my integrity and professionalism in ways subtle and not, sometimes openly wondering if a form of race loyalty had blinded me. Critics who once challenged me to better explain my positions, and respect theirs, in healthy, if passionate, back-and-forths, stopped dissecting my arguments and largely refused to take them seriously, capable of viewing me only through an Obama-tinged lens.

They would take me seriously if I joined others in slamming or disagreeing with Obama, the fouler the language I could muster to criticize him the better. Being the black dude who took the black dude in the White House to task, no matter the substance or merits of a position, was the quickest way to confirm I wasn’t race blind. It is as though many believed that sometime in November 2008 I had undergone a lobotomy. They were either incapable or unwilling to consider that the difference between pre- and post-Obama could lie within their own brains, and hearts, that a new racial reality had flushed to the surface unintentional racial stereotypes they had allowed to flow through their minds undisturbed for years.

Unknowingly, they had reduced me to just another black guy agreeing with the black guy in a White House that up to that point had been reserved for white men in ways they had never reduced white writers to being race-inspired cheerleaders of what had been the country’s uninterrupted parade of white presidents, no matter how many times those white writers agreed with the white guy in the White House, no matter how many times they patiently tried to explain the fellow white dude’s position, or impatiently tried to dispel myths about the man with whom they shared a skin tone, in an effort to create space for honest debate that could get us beyond talking points and exaggerated fears. They weren’t driven by a purposeful racism, but rather a passive ignorance, a refusal to grapple with any uncomfortableness that challenged their deeply held views.

Political scholars have noted that there’s been a marked shift in ideology toward hyper-partisanship that has intensified in recent years. They’ve also conducted research showing that in this new reality, political bias sometimes outpaces the ethnic and racial kind, though this may be in part due to the greater social acceptability of political bias.

There’s little doubt that’s true. But it doesn’t explain it all. Race is a still an under-explored factor in the shift. My politics and perspective didn’t change because Obama was elected. Even if they had, that would still have not explained why the number of times I’ve been called nigger—directly and indirectly—had increased exponentially.

Obama was the first black person for high office for whom I had ever voted. I don’t know if I would have voted for Jesse Jackson in the ’80s, the first black man to make real noise in a presidential campaign by winning multiple primaries, had I been old enough. But I did not even consider voting for Democrat Al Sharpton when he was challenging the likes of John Kerry and John Edwards, or Republican Alan Keyes or a handful of other black candidates whose names I’ve forgotten.

Since Obama, I had a chance to vote for Tim Scott, who became the first black man elected to the Senate from a Deep South state since Reconstruction, but chose not to. His ideology too closely resembled that of ultra-conservative Jim DeMint, a white man who gave up his Senate seat and supported South Carolina Governor Nikki R. Haley’s appointment of Scott. I considered Herman Cain’s “9-9-9” campaign, a flash-in-the-pan 2012 presidential run that briefly saw the former pizza chain executive atop of early polls before a predictable flameout, more of a stunt than worthy of serious consideration.

Before Obama I had only voted for white candidates—for governor, the U.S. Senate, and the presidency—almost all of whom were men. Not only that, most of those for whom I pulled the lever were conservative.

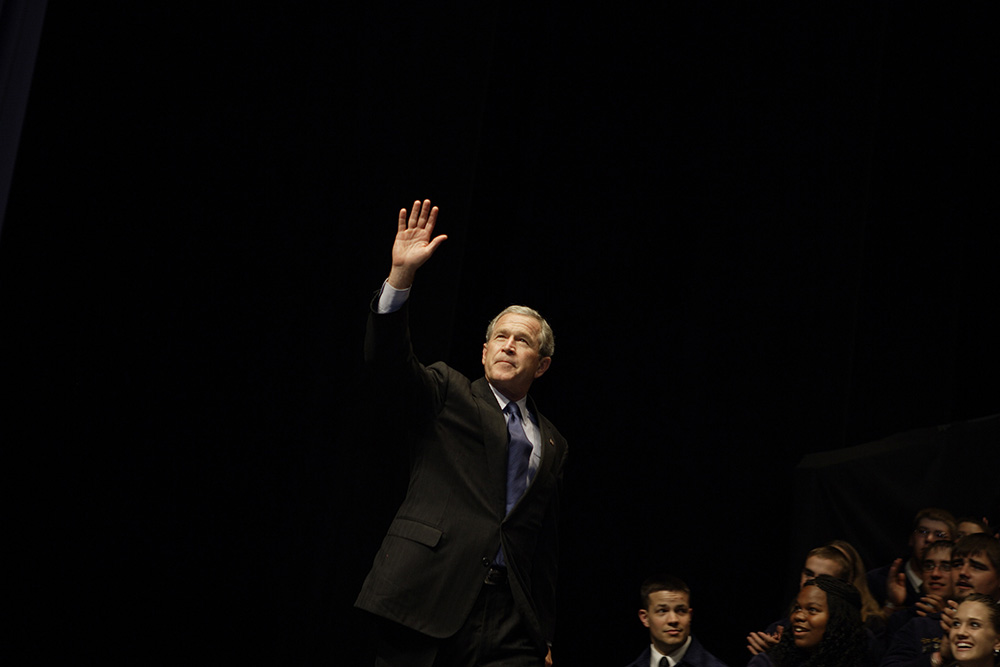

Republican George W. Bush, not Al Gore, got my vote in 2000. In 2004, a third-party candidate (I forget which one, maybe Ralph Nader) received my protest vote against a second Bush term after the Iraq-WMD debacle. I didn’t give Kerry a second thought.

What do most of the people for whom I voted before Obama for the most powerful seats have in common? Not gender, not political ideology, but race.

Each of them is white.

Despite that, in 2008 I, and millions of black voters, were accused of being incapable of seeing beyond race. Never mind that black voters had spent their entire adult lives crossing racial lines to vote, while the white people accusing black voters of a perverse racial loyalty to Obama had never found reason to vote for anyone who wasn’t white like them.

It reminded me of my days at Davidson College, an elite, mostly white liberal arts school in North Carolina. Many white students were quick to note the all-black tables in Vail Commons but never noticed the overabundance of all-white ones, never realizing those black students chose to challenge themselves by deciding to attend Davidson, knowing they’d be in the minority for four years, while it likely crossed the minds of not one white Davidson student to consider challenging themselves in a similar fashion at a predominantly black institution.

As a journalist, pre-Obama, I spent years recounting my voting history and explaining to Bush critics that they could disagree without hating him, could dissect his policies without subterfuge, needed to remember that he was a fellow child of God, that pushing conspiracy theories about his role in the 9/11 attacks and the lead-up to the Iraq war would only push us further away from the kinds of discussions and debates that were a must if we were going to be able to honestly determine which policies made sense, which ones didn’t, which ones had to be improved upon.

I wrote about race in the same terms, highlighting how Bush programs were doing wonders for those suffering from an AIDS and HIV epidemic in parts of Africa, how his cabinet was one of the most diverse in history and included the nation’s first black secretary of state, and how he appointed the first black woman to be national security adviser. During those years, I defended Colin Powell and Condoleezza Rice against charges of Uncle Tomism, which were coming from civil rights icons such as Harry Belafonte. I took Kanye West to task when he said Bush “doesn’t care about black people.”

I defended the likes of Rush Limbaugh and Don Imus and Bill O’Reilly against claims of racism and refused to jump on the bandwagon that became the Duke lacrosse rape case, in which three white players were accused of raping a black woman. The incident was held up by Duke professors and others as an instance that highlighted racism and sexism on campus, before the state attorney general declared the young men innocent and said they had been falsely accused by an overzealous prosecutor. I would repeatedly do the same for Tea Party members during the Obama era, reminding people not to label an entire movement by its worst, fringe elements, which were made up of people at Tea Party rallies with homemade signs depicting Obama as a bone-through-the-nose African witch doctor. And I began writing about how the health care system had been leaving too many people behind—black, white, Latino.

As a lifelong battle with a severe stutter had taught me to do, I looked for silver linings in dark political, racial, and economic clouds. That’s the way I thought, and wrote, long before Obama took his first oath, but after he took office, it became evidence of my supposed race loyalty.

Before Obama, those things generated “thank yous” and “you’re a credit to your race” and “more black people should listen to you” from countless white readers. I was a man of reason, deep thought, and fairness, in their minds, as I used my little perch to make the way for reasonable debate about the white dude in the White House and his policies. Since Obama, adhering to that philosophy brought me cries of “you’ve changed” and “race card” and “blacks need to get off the plantation” and “you aren’t doing your people any good.”

Some of it, no doubt, had to do with naked politics. Rank hypocrisy in politics is a feature, not a bug. But that’s not the full story. None of that explains why conservatives felt comfortable passing around a depiction of the White House lawn as a watermelon patch, a joke that compared Obama’s father to a dog, and a food stamp with pictures of ribs and fried chicken. It doesn’t explain why so many people who knew me long before Obama popped onto the scene unconsciously—and sometimes purposefully—reduced me to the amount of melanin in my skin.

It doesn’t explain why so many are committed to the belief that the only reason a black person would have chosen Obama was because of race. His work in Illinois to battle racial inequities within the criminal justice system, which appealed to me most because of my family’s experiences with prison, didn’t matter. His work with poor people in the streets of Chicago; his having been editor of Harvard Law Review; his ability in the U.S. Senate to help usher through ethics reform; his ideas about an ailing economy or being right about the Iraq invasion; his plans for health reform; his performance in the foreign policy debate against a grizzled war hero; the fact that a once-in-a-generation recession hit during a Republican presidency; his ability to make cynical crowds stand at attention—supposedly none of that mattered to black voters, only race.

For a long time, I kept a running list of all the ways I disagreed with Obama, ready to pull it out to show I was more than just about race

That’s why I’m tired. I’ve spent the past six and a half years studying and researching and interviewing and listening more than I did the previous decade. For so many people, none of that matters if it leads me to the conclusion that the black dude in the White House has done something well. And it hasn’t just been coming from white conservatives.

Black liberals such as intellectual Cornel West seem to have concluded that black journalists are cowed or simply want to cozy up to the White House if we don’t adhere to their hard-left views. I never expected Obama to be as leftist as West did and didn’t want him to be. I didn’t spend years voting for conservatives and liberals because I believe one ideology trumps the other.

For a long time, I kept a running list of all the ways I disagreed with Obama, ready to pull it out and re-post on Facebook or elsewhere to show I was more than just about race. I found myself repeatedly boasting about how Obama failed in his efforts to rescue the everyday homeowner. His administration quickly bailed out the banks, a necessary evil, I said, but missed a chance to help the middle class with a mass refinancing and mortgage modification plan.

I began writing about the ethical problems with Obama’s overuse of drones, though I think they are effective anti-terror tools and likely caused less collateral damage than a ground war would. As I supported the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA), I reminded readers about its flaws.

I documented the ways the economy was emerging from the worst downturn since the Great Depression but didn’t shy away from pointing out the lack of significant wage growth. I passed along scathing critiques from a variety of writers about Obama’s handling of privacy and press freedoms.

I expressed disgust that Obama would take occasions such as Father’s Day to excoriate absent black fathers. (While I was doing that, I was receiving messages from white conservative readers lamenting that Obama never talked about black personal responsibility.)

Obama was wrong on gay marriage, and his stiff-arming of the Muslim community during the 2008 campaign was weak, I was quick to say. His views on gay marriage are still wrong because he claims it is a state issue, I’ve told everyone who would listen.

I kept the Obama-failure list for a long time, until I realized I never pieced together such a list when Bush was in office. I didn’t count the ways local white politicians, who dominate Myrtle Beach area politics the way they have on the national level, had disappointed me. Only for Obama did I feel the need to be able to document, at a moment’s notice, how I disagreed with him to prove I was above race. I know now my doing that did the opposite. I treated Obama differently because I was trying to prove I wasn’t treating him differently. It affected me in ways I’m only now willing to admit.

That’s why I’m tired, because even as I battled that demon, I refused to play along with the over-hyping of false conspiracies such as those that surrounded the Ebola outbreak, the Benghazi tragedy, and the IRS review of conservative groups. I kept pointing out the duplicity of the Republican Party leadership, which tried to thwart Obama at every turn while claiming it was the president’s fault bipartisanship hadn’t taken hold as he promised. I loathe the Republicans’ state-level attempts to roll back voting rights and have repeatedly said so.

And I have not been shy about my support for health reform, which, while flawed, is a major improvement. It has contributed to the slowest rate of health care inflation in half a century; brought health insurance to 16 million Americans so far; cost overall less than what had been forecast; has helped millions of seniors afford prescription drugs; and extended the life of Medicare by at least a dozen years.

I don’t support the ACA because of Obama. I support the ACA because it is helping people in need and will put a dent in inequality by taxing those most able to benefit the most needy. I support the ACA more than I support Obama.

I refused to vote for Bush for a second term because of the debacle that was the Iraq war and the false WMD claims. In 2010, I declared Obama would not get my vote in 2012 if he didn’t find a way to push through health reform. That support stems in part from my knowledge that the GOP has refused to do anything to truly address the country’s out-of-control health care problems and has opposed major reform efforts by Bill Clinton and Obama.

Only one party was willing to do something significant about one of the most vexing problems facing this country—rising health care costs are among the nation’s top fiscal threats—and it was being led by the nation’s first black president, not the party I voted for several times before 2008.

For a lot of people, little of that matters, no matter how many times I spell it out. I’m black and Obama is black and that’s all they need to know.

That’s why I’m tired. I’ve spent the Obama era trying to do my job the way I know I should, the way I had before him, fearlessly assessing the news and policy, while also trying to beat back the burden that is race.

It hasn’t been easy. Several times, I wanted to throw up my hands. I wanted to be like others who had distilled Obama down into his simplest parts. I wanted to experience the freedom a large number of columnists and pundits had, not caring about nuance or fairness or quoting in context politicians with whom they disagree instead of as though they were caricatures, not complex human beings.

Part of it stems from the parallels I noticed between Obama’s life and mine, which made the struggle to support Obama policies personal in a way they never were during the Bush years.

Obama was once considered too black, then not black enough, as have I. A man snubbed him during the 2008 campaign, refusing to shake his hand, the way a white man I was interviewing for a story about the economy wouldn’t shake mine. Obama grew up disadvantaged but eventually made his way into elite institutions of higher education, like I did. Some of his accomplishments were demeaned by those saying they only occurred because of race in the same way some of mine have been discounted, no matter how hard I worked to achieve them, no matter how many obstacles I had to overcome. He’s been called “uppity” and “nigger” and other disparaging terms, like I have.

The irony is that during 2008, I understood the political game well enough to know that Obama’s approval rating would begin to fall once the hard task of governing began. That didn’t surprise me. Being reduced to the color of my skin by even people who knew me well, no matter how hard I tried to be fair and comprehensive in my thinking and writing, did.

Though I was stubborn enough to (mostly) do my job the way I believed I ought to, that hurt. It wore me down.

I’m overjoyed that I lived through the time during which the country—founded upon the contrasting beliefs that all men are created equal and that black people are inferior—elected its first black president. If another black candidate emerges in 2016 or beyond as the one I should choose among mostly white candidates, I’ll cast my ballot for him or her and professionally will endeavor to treat that presidency the way I know I should. I’m stubborn that way.

I’m tired, though. In 2008, I didn’t know a long hoped-for historic breakthrough could make me feel this way.

I’m tired, but not nearly as tired as those who were beaten on a bridge in Selma 50 years ago, or those killed a century before in the nation’s bloodiest war, or my parents and aunts and uncles, who toiled and overcame obstacles and slights that make the ones I’ve experienced these past six and a half years seem like child’s play.

So, yes, I’m tired. But because of what happened in November 2008, my kids won’t be nearly as tired as I am.