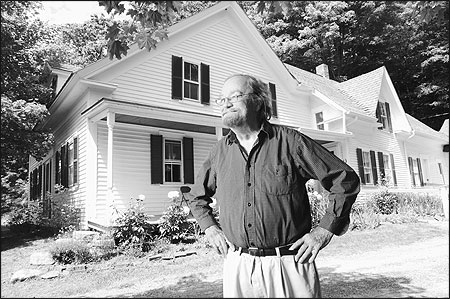

Donald Hall at his home in Wilmot, New Hampshire, whenhe was named the new poet laureate of the United States. Photo by Ken Williams/Concord Monitor.

America's new poet laureate, Donald Hall, has been the Nieman Fellows' poet laureate for more than a decade. He makes an annual pilgrimage to One Francis Avenue to answer this question: What can journalists learn from a poet? Quite a lot, it turns out, about both their craft and the poet's realm.

I have known Don for more than 25 years, and for nearly all his visits to the Lippmann House, I have served as his chauffeur, introducer and trusty sidekick. In addition, since 1979 Don has often visited with my news staff at the Concord Monitor for brown-bag lunches. Combining these sessions with the Nieman visits, I have probably heard Don discuss poetry and writing with journalists 20 times.

These sessions are always pleasing and never routine. Journalists want to hear all kinds of things from Donald Hall.

At one Nieman session an editor from the New Yorker asked him if it was true that being a poet helped a man meet women. Don answered that he took up his pen as a young man because he had been cut from the baseball team and maybe writing would make the cheerleaders like him — no, love him. Knowing Don as I do, I understood that this answer was only partly tongue in cheek.

A fellow at the same session had just read a new biography that portrayed the English poet Philip Larkin as a scoundrel. The fellow asked Don if Larkin's wretchedness as a person should change the way readers view his poetry. No, Don said, you could probably distill to minutes and seconds the portion of a poet's lifetime during which he created the poems that made his reputation. The rest of the time the poet might have been sticking up filling stations or intentionally running over cats with his automobile. "Trust the poems, not the poet," Don said.

Revisiting Words

Don almost always brings some of his own poems in progress to read to the fellows. He is obsessive about revision, sometimes writing more than 100 drafts of a poem and numbering each. Thus at the top of a draft you might see "Weeds and Peonies/93" and think that Don numbers his works as some modern artists do. In fact, it is draft No. 93 of the poem.

As I left my first interview with Don in 1981, he gave me an early collection called "The Alligator Bride." In the inscription, he directed me to a poem called "The Man in the Dead Machine," saying it was one of his favorites. I opened to this poem and found that he had revised it in red ink right on the page of my book. A couple of years later, while introducing him to my editors and reporters, I told them about his obsession with revision, and I brought the book along to show them the red ink. Don reached up, took the book from my hand and wrote in his latest revisions in black ink.

Journalists, of course, lack the luxury of perpetual revision, although many of us, particularly early in our careers, have surely longed to follow our newspaper carriers around in the morning to correct in each paper the error that occurred to us too late and now appears under our byline. But even under the tyranny of daily deadlines, journalists can help themselves by thinking like a poet. What Don often seeks in revision is precise language. On this score, there are useful aphorisms that I have heard him offer more than once at Nieman gatherings: "There are no synonyms." "All adjectives limit." A Nieman Fellow once asked Don if he considered himself a regional poet. I was seated beside Don and felt the earth rumble beneath my chair. "Any kind of label is diminishing," he said.

In this age of accountability, or at least the quest for it, more than one Nieman class has taken up the most elemental issue of all: What are your aims as a poet, and how do you measure whether you have achieved them? Don's answer one year began with what a poem is not. It is not an explanation, an argument or an idea, he said. Rather it is a creation that he hopes is true to the emotions — mainly his emotions but the reader's as well. A poem is also a quest for beauty but not just for beauty's sake. It is communication; it seeks a connection.

Fellows often ask Don about Robert Frost, just as reporters writing about him being named national poet laureate this past June almost inevitably compared him with Frost. Don has lived with this question, and contemplated the work of Frost, for 60 years. He regularly raises his assessment of how many great poems Frost wrote. "Every time I look up, he has written another one," he once said.

Don appreciates Frost for his stubbornness and his fierce will to survive. He sees a personal parallel with Frost in that they both moved to northern New England from someplace else. This last has an advantage, allowing the poet to be "the outsider who picks things up," as Don once put it. On the other hand, Don wrote much of his poetry in free verse because whenever he wrote in iambic pentameter, he worried that he was imitating Frost. Free verse was truly liberating for him.

Listening to Words

A sense of place is important in the poetry of both Frost and Hall, and both were attracted to elegy. But to me, the clearest comparison of Frost with Hall is in the central role of sound in their poetry. As Don sees it, Frost took pleasure in saying things as no one had ever said them before. "He wants two things at once: the sound of speech and absolute metrical regularity." Frost used the sounds of sentences to capture character. Don encourages those who ask about Frost to read "Home Burial" carefully to detect Frost's use of sound to convey the male and female qualities of his speakers.

To understand of the central importance of sound to Don's own work, you only had to be present during his session with the Nieman Fellows this year. The exchange began when Curator Bob Giles asked Hall about "Summer Kitchen," a lovely poem in which the narrator looks from another room into the kitchen and sees his wife licking tomato sauce from her fingertips. To Bob, it was a scene told through a poet's eyes, much as an artist might observe and paint it. No, no, not at all, Don replied. The poem began with sounds. And without referring to the text he rattled off the long vowel sounds of "Summer Kitchen" — "high, light, wine, sunshine" — and spoke of his pleasure in working "candle" and "miracle" into the rhyme scheme. With a poem, he said, if you toil to get the sounds right, the scenes and the narrative will take care of themselves.

Of course, journalists cannot adopt such an attitude, trusting that if the sound of what they write is true, the content of their stories will follow. Don brags to reporters and editors about the lies in his work, implicitly arguing that this lying is essential to achieving art's larger truth. Information is the enemy of art, he likes to say. And yet even though information is the essence of our work, we've all had the experience of reading a news story and realizing that the writing is exceptional. A closer look usually shows that the writer has a special consciousness of the sounds of the words on the page. It is one thing we mean when we say a reporter has a good ear.

Sound is also an issue that Don raises in talking about poetry in translation. Having traveled widely, he is always interested in the foreign Nieman Fellows, and they in him. Don's late wife, Jane Kenyon, translated poems by Anna Akhmatova, and they went to China, India and elsewhere together to share their poems. At Nieman gatherings, the question about foreign poetry is often why so much is lost in translation. Don's answer begins with the sound, an impossible challenge for even the most gifted translator. It also includes the subtleties of language and culture that almost no foreign reader could know.

Perhaps my favorite subject in Don's talks with journalists is the dead metaphor. A dead metaphor is a word we use, often a verb and usually for the sake of colorful writing, that no longer calls to mind the word's actual meaning. Overuse has killed the comparison.

Once, a journalist asked Don for some examples of dead metaphors. He picked up a copy of that day's Concord Monitor and turned to the editorial, which, as it happened, I had written. In no time he had zeroed in on (dead metaphor — or "DM," as Don is fond of marking them in text) the verb "trigger." I had used it in a sentence that said some action "triggered a discussion." Of course, no one reading this verb would think of an actual trigger and, if a reader did, the association would be comical, raising the thought of people willing to talk only with a gun to their heads.

Because poetry is the purest form of verbal expression, Don is always quick to condemn dead metaphors in poems. In journalism, because we are writing the first rough draft of history, we are highly susceptible to using dead metaphors. Don's point is that being aware of this tendency should make us think twice about them and be more precise in our language.

I hope I have not left the impression that listening to Don is an exercise in taking lessons from a poet. Any Nieman Fellow who has sat with him will tell you that these sessions enlighten and amuse far beyond practical considerations. Poetry is a pleasure of the mouth. Poets labor in a centuries-old tradition that modern life has expanded in both form and content. In sampling this pleasure and these traditions, the fellows have delighted in their worthy laureate for many years.

Mike Pride, a 1985 Nieman Fellow, is the editor of the Concord Monitor. He also has coauthored, with Steve Raymond, "Too Dead to Die: A Memoir of Bataan and Beyond."