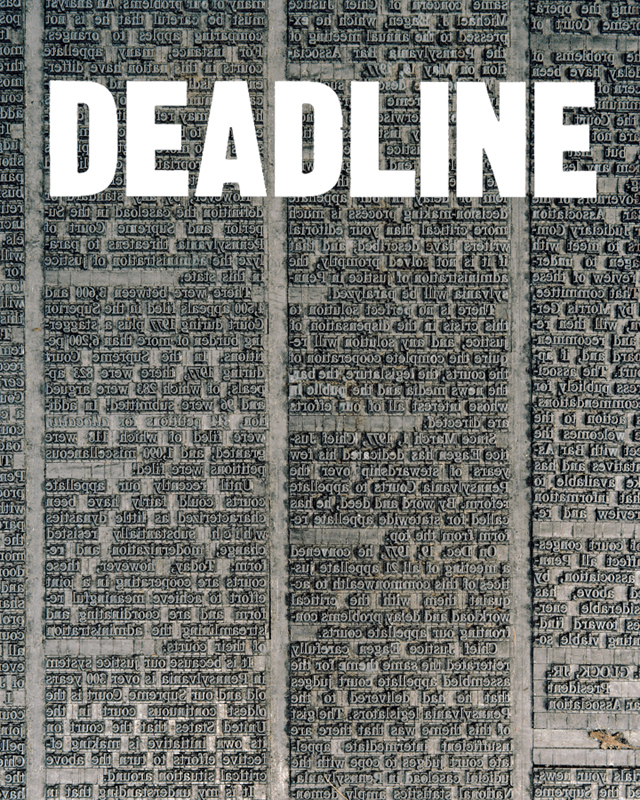

The following is an excerpt from Will Steacy's "Deadline."

Perhaps like many children of newspaper reporters, I came to understand small pieces of my father’s job before the full picture of what he did came into focus. I knew he always came home later than my mother, and that occasionally, as he was “putting a project to bed” as he called it, he barely came home at all. I knew his work involved a lot of time on the phone, many piles of paperwork and stacks of books. I knew that his workplace seemed somehow less serious and more serious than other offices. I knew that for several weeks when I was very young, his union went on strike and for once he was actually home all day, during which time he did things like repaint a room and pick me up from school.

We lived close to the Inquirer, and on weekends I sometimes went with him to the castle-like building at 400 N. Broad St. when he needed to pick something up. We’d climb up through the wide stairwells and enter a low-ceilinged room that seemed ancient, dusty and utterly without light. Through there we’d get to the office he shared with his writing partner. In my memories that room is even darker than the newsroom, almost a closet, and covered with teetering towers of documents and floor-to-ceiling file folders that completely obscured the desks.

The first time I saw the new Inquirer newsroom as an adult and a member of the staff, it seemed too clean, too bright—if it weren’t for those wide stairwells, I wouldn’t have believed it was the same building. Then again, it has always seemed kind of unbelievable that I ended up working there at all.

And yet, it never felt modern. There were ghosts in the corners of that building, and in the sea of empty desks. There were many times walking through that carpeted room when I would suddenly remember standing in the newsroom on one afternoon in 1989, surrounded by people who were cheering and applauding because my father and his writing partner had won their second Pulitzer Prize. The pictures from that day now have the dusty quality of a long-ago time; some are even in black and white.

More than 20 years later I was fortunate enough to find myself in the midst of another such celebration as a team of Inquirer reporters was awarded a Pulitzer Prize. The crowd of people there to witness the moment seemed so impossibly small, it all felt so quiet. I told myself it felt different because it was I who was bigger, but when I look at the photographs I can see it wasn’t my imagination.

Decades ago, the Inquirer had reporters stationed all over the country and even in the world. There were bureaus in Moscow, in London. There were reporters sent to cover wars. By the time I arrived there in 2008, that was all, or mostly, gone.

I grew up thinking of newspapers not as companies but as institutions or societies, places where co-workers played pranks on one another and sometimes showed up drunk and worked hard but not like normal people worked. In that sense, it shouldn’t have been such a surprise to me that as I got older, it was the only job I wanted.

But in a strange way, it doesn’t always feel like I work at the same company where my father once worked. Even before the Inquirer was forced to pack up and leave its iconic white-towered building and settle in a sparkling office space that was once a department store, it didn’t always feel like the same place. Much of what goes on in a day at the Inquirer now would be unimaginably foreign to my father. And I have often wondered what I would think of the way things were back then.

Some measure of shared experience will always bind one reporter to another, as it has for my father and me. There are things we never have to explain to each other: dinner plans that must suddenly be cancelled, the need to make a phone call or two for work on Christmas morning, an editor who doesn’t understand the story being told.

When I was a teenager, my father told me, without exactly meaning to, what his job was all about. I’ve tried to live by it ever since. “Try to tell people something they don’t know,” he said. It’s as close to a family motto as we will ever have.

Reprinted from “Deadline,” by Will Steacy. Copyright © 2014 by Will Steacy