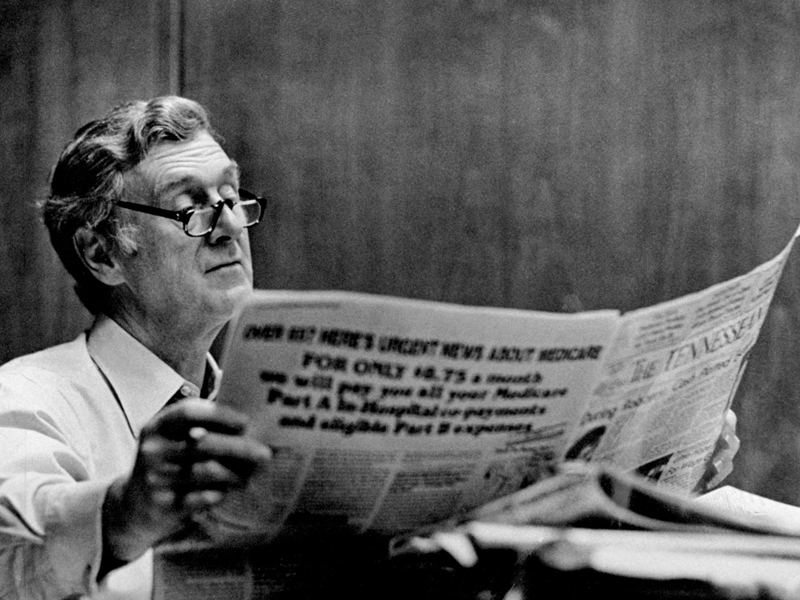

John Seigenthaler, NF ’59, who died July 11 at age 86, was a throwback to the crusading newspaper editor of legend. During his 39 years at The (Nashville) Tennessean—as reporter, editor, publisher and chairman—the newspaper drove criminal politicians from office, reversed stolen elections, and remained at the forefront of the struggle against the forces of segregation. He was an advocate for journalistic ethics and fairness. As the first editorial page editor of USA Today and president of the American Society of Newspaper Editors, he worked to open the industry to women and minorities.

My remembrances of John Seigenthaler could be a novel, a glorious tale of a rough-edged kid from a mill town on the wrong side of the Cumberland River set straight by a fortuitous encounter with a celebrated Nashville newspaperman.

Seigenthaler placed a bet on me when, two years out of high school, I was struggling to pay my way through college. Why, I don’t know. Maybe it was because I was a street kid, grandson of a cop he knew, oldest sibling in a large Catholic family as he had been.

When I worked for him at The Tennessean from 1962 to 1972, he was a hard master. Early on, I attended college on a Wall Street Journal scholarship, working weekends and evening shifts as a reporter. One night he dispatched me to Memphis to find a state senator who had disappeared the night before he was to cast the deciding vote in a hotly contested race for lieutenant governor. At 5 in the morning I found the senator’s car, but he drove off and I lost him. Seigenthaler said, “Well, find him again. And if you don’t, there’s a pretty good paper down there in Arkansas. Maybe they can use you in Little Rock.”

I found him, and I loved the work so much that I marched into Seigenthaler’s office one day to announce that I was quitting college so I could devote more time to my job. “That won’t work,” he said. “Why?” I asked. “Because if you quit college, I’ll fire you and you won’t have a job.” Meeting over.

A month after I finished my degree in 1965, The Tennessean sent me to be its one-person Washington bureau. My Nieman Fellowship at age 27 likely came on the strength of my supporters—journalism legends Eugene Roberts, NF ’62, and Jack Nelson, NF ’62—neither of whom would have heard of me had Seigenthaler not sent me tagging after them around the South on a lot of big stories.

Most journalists and civil rights leaders know about Seigenthaler’s passionate support of First Amendment rights and equal justice for every race, creed, color, and gender. But the remarkable aspect of my Seigenthaler stories is that they are not unique. At a reunion the night before his funeral, I heard dozens of stories like mine.

My remembrances of John Seigenthaler could be a novel, a glorious tale of a rough-edged kid from a mill town on the wrong side of the Cumberland River set straight by a fortuitous encounter with a celebrated Nashville newspaperman.

Seigenthaler placed a bet on me when, two years out of high school, I was struggling to pay my way through college. Why, I don’t know. Maybe it was because I was a street kid, grandson of a cop he knew, oldest sibling in a large Catholic family as he had been.

When I worked for him at The Tennessean from 1962 to 1972, he was a hard master. Early on, I attended college on a Wall Street Journal scholarship, working weekends and evening shifts as a reporter. One night he dispatched me to Memphis to find a state senator who had disappeared the night before he was to cast the deciding vote in a hotly contested race for lieutenant governor. At 5 in the morning I found the senator’s car, but he drove off and I lost him. Seigenthaler said, “Well, find him again. And if you don’t, there’s a pretty good paper down there in Arkansas. Maybe they can use you in Little Rock.”

I found him, and I loved the work so much that I marched into Seigenthaler’s office one day to announce that I was quitting college so I could devote more time to my job. “That won’t work,” he said. “Why?” I asked. “Because if you quit college, I’ll fire you and you won’t have a job.” Meeting over.

A month after I finished my degree in 1965, The Tennessean sent me to be its one-person Washington bureau. My Nieman Fellowship at age 27 likely came on the strength of my supporters—journalism legends Eugene Roberts, NF ’62, and Jack Nelson, NF ’62—neither of whom would have heard of me had Seigenthaler not sent me tagging after them around the South on a lot of big stories.

Most journalists and civil rights leaders know about Seigenthaler’s passionate support of First Amendment rights and equal justice for every race, creed, color, and gender. But the remarkable aspect of my Seigenthaler stories is that they are not unique. At a reunion the night before his funeral, I heard dozens of stories like mine.