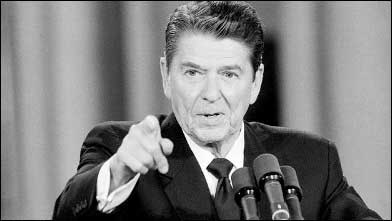

Reagan said government was the problem...and paved the way for that to become a reality. Photo courtesy of the Associated Press. |

This article originally appeared on www.niemanwatchdog.org.

Is the BP disaster indicative of a problem in government extending well beyond one small agency in the U.S. Department of the Interior? We should be asking how badly the federal bureaucracy has been damaged by decades of neglect, mismanagement and anti-government ideology.

So far the primary federal culprit behind the BP environmental disaster is the Interior Department’s Minerals Management Service — MMS. Its failings, both past and present, have made it a favorite media target over the last six weeks. From sex and drugs to serial exemptions from environmental reviews, MMS has come to represent everyone’s worst fears about bureaucratic incompetence, and the media are now making the connection that this “incompetence” has been in the service of the interests of the oil industry.

The press has done an admirable (albeit belated) job with the technical complexities of MMS’s administrative failings. What is not being asked, and what the press needs to focus on, is whether MMS’s problems are endemic to the entire federal government.

When he became Interior Secretary, Ken Salazar claimed to understand the problems at MMS. Yet he reacted as if the agency’s problems, detailed in report after report and article after article, are the isolated acts of a few bad apples, not an agency-wide infection, and he apparently continues to believe that. The Secretary’s early reform efforts, greeted with fanfare and applause when announced, seem, in retrospect, meager and cosmetic.

The very tragedy of the BP story underlined that the “cultural problem” at MMS extends well beyond a handful of bureaucrats wining and dining on industry’s dime. Where were the rest of the regulators, and why they weren’t protecting the public’s interest? Unfortunately, the regulators were exactly where they were intended to be: serving the interests they were trained to serve. The sad truth is that the middle manager career bureaucrats — those who might have warned Secretary Salazar or his hapless former MMS director — likely would not have even recognized the bias in their standard operating procedures.

Is MMS more typical than unique in its approach to meeting its regulatory responsibilities? Articles about regulatory capture — federal agencies beholden to regulated industries — were becoming almost ho-hum; the FDA, the NRC, the DCAA (Defense Contract Auditing Agency), and so on. Worse, MMS is not unique in its contributory role to a national calamity. Who can ignore the contributions by the Federal Reserve and the Securities and Exchange Commission to the current economic crises? The BP explosion evidences that it is long past time for us to consider whether these dots are all connected.

In 1980 Ronald Reagan famously announced, and often repeated, that the government was not the solution; the government was the problem. This slogan did not just discourage competent people from careers in regulatory agencies, it represented a new approach to regulation. Government regulation was no longer to be a constraint on business behavior. Government should not be an obstacle to all the good that could be achieved through unbridled enterprise. Regulators were to be active promoters of the businesses they were to regulate. Agreeing with President Coolidge, Reagan believed that “the business of America is business,” and the government should get out of the way. Industry self-regulation and “free market” economics became the substitute for government regulation.

Conservative political thinkers actually argued that it was impossible for government to impartially regulate in the interest of the public and the nation. For decades they have held that all government is bad and less is always better. As a result we had decades of indifferent and incompetent leadership in the regulatory agencies. In recent years they have frequently been staffed with people hostile to their basic purpose.

Indeed if it does anything, the disaster in the Gulf demonstrates the folly of this approach to government. And the lesson is reinforced by the cries for help from the conservative political leadership of the Gulf Coast states — who in the past led the charge for smaller and less intrusive government. Beyond all question it demonstrates the need for competent regulation that is not controlled by the interests it is supposed to regulate. It destroys the simplistic notion that the interests of business coincide with those of the broader community.

In his campaign for president, Obama promised to make government service “cool” again. The model for this is what was accomplished by those who led us out of the Great Depression and to victory in WWII. But as president, Obama has a long way to go. He must recruit and inspire a whole new crop of middle managers imbued with a positive attitude toward government service. Budget problems should not stand in the way. Given what has happened to the economy, government jobs have become quite attractive, at least in terms of compensation. What is needed is leadership — which unfortunately will come too late for the Gulf.

Henry M. Banta is a partner in the Washington, DC, law firm of Lobel, Novins & Lamont.